Our last post explored some examples of the Highland cantonment schemes proposed by British government officials after Culloden, their locations largely selected based upon a combination of local banditry, general lawlessness, and noted recalcitrance toward the policies of the Whig administration of George II – defiance often manifested by varying levels of Jacobitism. Some of the loyalists who were responsible for influencing the creation of these garrisons had witnessed the violence and disorder firsthand – like Donald Campbell of Airds, whose own property was savaged, ironically, by soldiers of the British army.1 Nonetheless, the unpredictable and complex lattice of malleable alliances, divergent loyalties, and partisan politics in certain remote areas of Scotland essentially guaranteed that some kind of official program of regulation would be instituted after the brutal coda of yet another armed rising.2

Access and control were collectively the name of the government’s game in eighteenth century Scotland. The Western Highlands bore the brunt of unconscionable retaliation and enforcement after Culloden not because it provided the largest number of rebels who bore arms (it did not), but because it was so difficult to regulate due to the remoteness of its communities and the severity of its weather and terrain. While the isolated villages and steadings in many regions of the Highlands provided distance and shelter for their occupants, that same isolation also enabled heritable chiefs to maintain control of their clans with little interference, as well as allowing currents of Catholicism to endure within a rapidly reforming Scottish populace.3 ‘The old way of life’ may have been desirable for some heritors, but plenty of others were progressive improvers with interests in both imperial ventures and global mercantile investments.4 This alone adequately disproves the popular myth that the Forty-five was a conflict of atavism versus progress.

Not only because of the remoteness of these communities, intelligence was notoriously difficult to obtain for government agents, despite many prominent spies being deployed during and well after the 1745 campaign. Those in charge of hiring out agents were repeatedly stymied by the unwillingness of the common people to help capture notorious rebels or other lawbreakers secreted within towns and villages throughout Britain. Such reluctance was not necessarily an indication of Jacobite loyalty, but more often a gauge of the desire to stay away from the dangerous game of choosing sides. This act of ‘safeguarding locale’ would have likely been made in the interest of self-preservation and was commented upon in Aberdeenshire, Crieff, and the Western Highlands, joining other exasperated accounts from places like Amulree, Gairloch, and Dalwhinnie.5 Despite these frustrations in some localities, officials charged with keeping tabs on rebel activity relied upon a few trusted envoys who either were able to blend in well with the environs in question or who were already well established within them.

I am still under the utmost difficulty in getting Intelligence, for the People in this Country keep every thing they know very private, Such as I pay and promise great Reward to for returning with Intelligence I see no more off.6

In addition to leaning upon well-entrenched networks of Presbyterian ministers for reliable information pertaining to Jacobite progress and numbers, particular individuals were repeatedly used because of their dependability and accuracy.7 One of these men was the Stirling-born Patrick Campbell, who was sent by the Earl of Albemarle on a fact-gathering mission into the Scottish Highlands during the autumn of 1746. Traveling alongside another man with the surname of Stuart, Campbell traversed 483 miles of ground over forty-six days, commencing in Edinburgh and navigating a wide section of the western coast and Isles, over Glenshiel and Glenmoriston in the north-west, and southward through the Perthshire Highlands, concluding the journey at Kinghorn in Fife at the end of November. His report contains a remarkably detailed account of the country’s disposition and surely inflamed the government’s paranoia that Jacobite aspirations – if not intentions – were in fact still very much alive despite the slaughter at Culloden.8

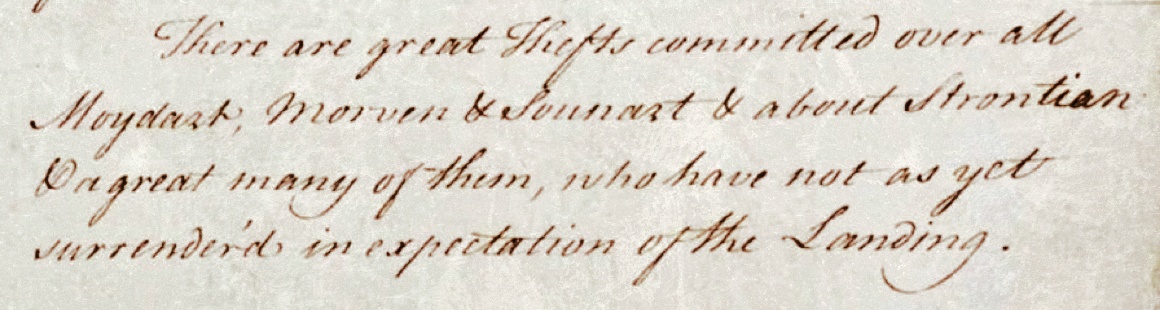

The main purpose of Campbell and Stuart’s expedition was to gauge the temperament of the most disaffected areas of the Highlands, as well as to report on the presence of arms and ammunition still in circulation amongst potential rebels. Lord Justice Clerk Fletcher and Albemarle also had an itch to track down what happened to the gold rumored to have been sent from Spain for Jacobite designs, and this would be as good an opportunity as any to gather information on its whereabouts. The report, presented in journal form, describes a string of secluded communities that were recovering from the violence and diminishment of civil war, many of which were still holding out hope for another landing from France. The most common depictions of these villages and farmsteads include hopeful men and women who had mostly surrendered to the authorities, despite their collective appearance of being overwhelmingly inclined against the government. Others are identified as still hiding out; at least seventeen notable Jacobite officers are named, some of whom Campbell describes as still giving pay to their men and continuing to ‘spirit them up’:

There was a great many of the Inhabitants of this place [Appin] killed at Culloden, which makes Meal more plenty in that Country than many others, it being all Labour’d in the beginning of the Year & equally good for Grain as Graizing, found such of them as were at home on the same Expectations of a Landing & ready to Join it.

Supplies were surveyed for each community, including grain, meal, rum, brandy, and wood fuel (fireing). The conditions of burned homes are likewise recorded, and the slow process of rebuilding is hinted at even through the starving conditions suffered by many. Even the damages inflicted by the King’s own troops upon farmsteads in Morvern were starting to get repaired after many months of abandoned production and lack of rental income; Campbell noted that the people there were expecting full ‘redress’ after the next French landing took place, though it is not clear if that meant monetary recompense or corporeal vengeance. Fourteen steadings are listed as being burnt out in Morvern alone, all of which are described as having harbored Camerons and Macleans who were – to a person – active in the rising:

Aulashdale • Auchalinan • Drimeoragig • Ferrnish • Killoundan • Laggan

Drimnin • Sallachan • Funnary • Savery • Auchnaha • Kiell • Knoch • Artornish

Farther north in Lochaber around Loch Arkaig, home to the pervasive legend of hidden Jacobite treasure, the inhabitants left behind were not yet on the mend. Macdonald of Keppoch’s lands, as well as those of Cameron of Lochiel, are described as having been ‘all burnt’, and with few homes left standing in which to take shelter, some people were sleeping in shielings up in the hills:

Went from that [Fassifern] to Locharkeg & found the same burnt also, Such of the People of that Country as were not killed at Culloden live in the hills in small Hutts & a great many made their Escape into Knoydart as they could not stay in their own Country in being upon a pass from Fort William & much afraid of the Red Coats.

Evidently with little left to lose, Campbell asserts that the locals were ‘full of the Spiritts of Rebellion’ and had ‘great assurances’ that there would indeed be another landing sometime in the spring of 1747. With homeless Lochaber folk drifting northward into Knoydart, widespread larceny was pronounced a daily issue, and this was allegedly spurred on by numerous tribes of Macdonalds, who are described in the report as ‘mostly Papists and great Thieves’. Glenmoriston was in a similar condition, devastated and penniless but nonetheless sheltering dozens of Grants in twenty different villages hoping to exact revenge upon Major James Lockhart, who had been especially brutal to them in the months prior to the survey.9 Just eastward in Glengarry, however, the land was so depleted of inhabitants that the expedition could only identify some women living in huts who were all near to starving.

Though Campbell painted a vibrant picture portraying nearly the entire north-west as being again ready to rise in arms just six months after Culloden, the ‘incensed’ dispositions of these Highland communities were likely tempered more by rampant lawlessness and chaos after the displacement of their families and the depredations inflicted upon their property in the wake of the battle – damage carried out by both Jacobite refugees and government troops alike.10 Regardless of cause, there were no clear signs of peace anytime in the future; the sheriff-deputy of Argyllshire, Archibald Campbell of Stonefield, remarked in the height of summer in 1746:

I am of opinion the Rebellion is quash’d, but do not at all See the troubles in the Highlands or Countrys bordering with those of the Rebells near an end, I rather think they are beginning.11

As the party ventured into the Central Highlands of Perthshire, where retributive destruction was less frequent, their interactions with the locals took on a different tenor. Rancor and agitation gave way to fatigue, and hope for another rising was replaced by the fear of being again forced to join should it occur:

Such of the Inhabitants of the Braes of Athol as we convers’d with, seem’d to be weary of Rebellion & complained much that they were forced out by Lord George Murray. And was informed that such of them as live in the High places of Athol went along with the People of the Braes of Mar in the habit of the Argyll Shire Militia with a red Cross upon their Bonnets & robbed & plunder’d wherever they Suspected Money or Goods.

Banditry, however, was just as pervasive as in the west, as some took advantage of the tumult to swindle hapless residents and travelers out of their belongings. We previously discussed the use of costumes and trickery by government spies to root out hidden Jacobites, and the situation in Atholl recorded by Albemarle’s agents shows unscrupulous outlaws employing similar techniques – this time in the guise of Campbell soldiers under employ of the state. Ironically, in Skye, disbanded companies of authentic Argyll militiamen told the government operatives that they were poised to flip sides and ’embrace the first opportunity of Rebelling’ if their commissions were not extended. The business of creating business continued on for all involved, even those who chose the ‘winning’ side in a messy conflict which contained few clear lines of loyalty.

Collectively, the facts outlined in this report exacerbated the alarm of British officials, with Lord Justice Clerk Fletcher commenting in mid-December 1746 that the account ‘shows the necessity of doing something to purpose’ in the localities cased by Campbell and Stuart.12 The persistent lawlessness and the significant number of known Jacobite officers still in hiding – some of which were revealed by the expedition – ensured that the government would continue to dedicate resources to snuffing out the seeds of rebellion once and for all.13 Patrick Campbell was used many times by British authorities in helping to relay intelligence about lingering Jacobite activity, but he was by no means the only one. Fletcher and Albemarle also employed Alexander Mcmillan in Lochaber, Dudley Bradstreet in England, John Millar and John Wright in Stirling, and Alexander Robertson of Straloch in Perthshire, amongst many others, during the rising and for years after it had concluded.14

Jacobitism was just one facet of the ‘North British problem’ faced by George II and his ministers, and the political and social subversion would indeed continue on even after the defeat of practical, militant Jacobitism.15 Empirical observance of the mood in the Western Highlands after Culloden proved that resentment and intransigence were still present in large pockets of Scotland and would require extensive suppression and regulation to prevent further organized rebellion. Despite Jacobitism being a distinctly international phenomenon, Hanoverian government policies designed to address these issues would be focused on the Highlands for at least another fourteen years, until which time another violent front would open up across the Atlantic in the New World. Remarkably, the state would go on to weaponize some of the same people once hunted during the Forty-five to redeem themselves by fighting for Britain’s imperial ambitions in North America.16

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and Open Access.