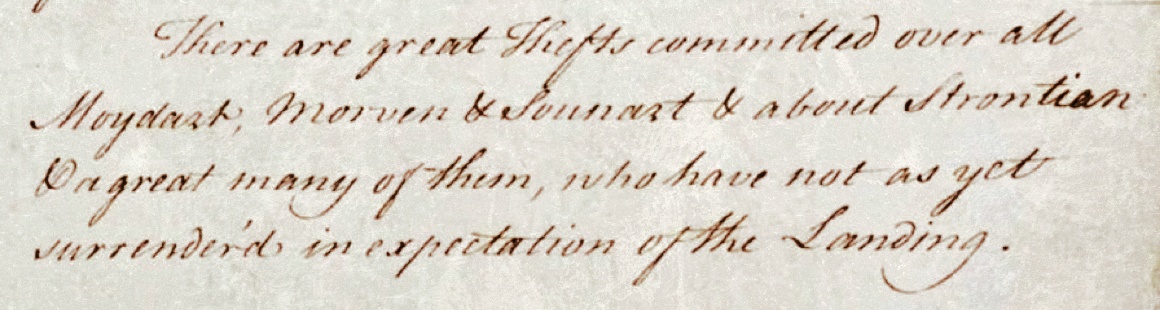

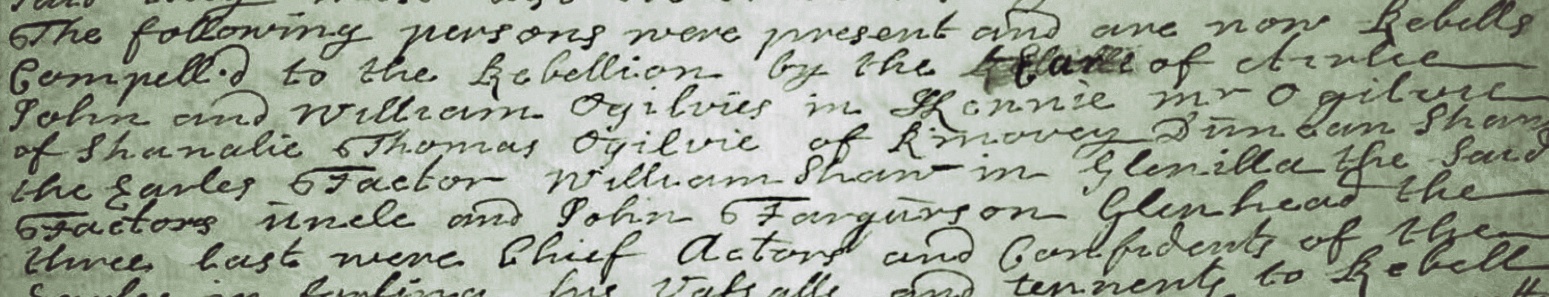

Our last post explored some examples of the Highland cantonment schemes proposed by British government officials after Culloden, their locations largely selected based upon a combination of local banditry, general lawlessness, and noted recalcitrance toward the policies of the Whig administration of George II – defiance often manifested by varying levels of Jacobitism. Some of the loyalists who were responsible for influencing the creation of these garrisons had witnessed the violence and disorder firsthand – like Donald Campbell of Airds, whose own property was savaged, ironically, by soldiers of the British army.1 Nonetheless, the unpredictable and complex lattice of malleable alliances, divergent loyalties, and partisan politics in certain remote areas of Scotland essentially guaranteed that some kind of official program of regulation would be instituted after the brutal coda of yet another armed rising.2

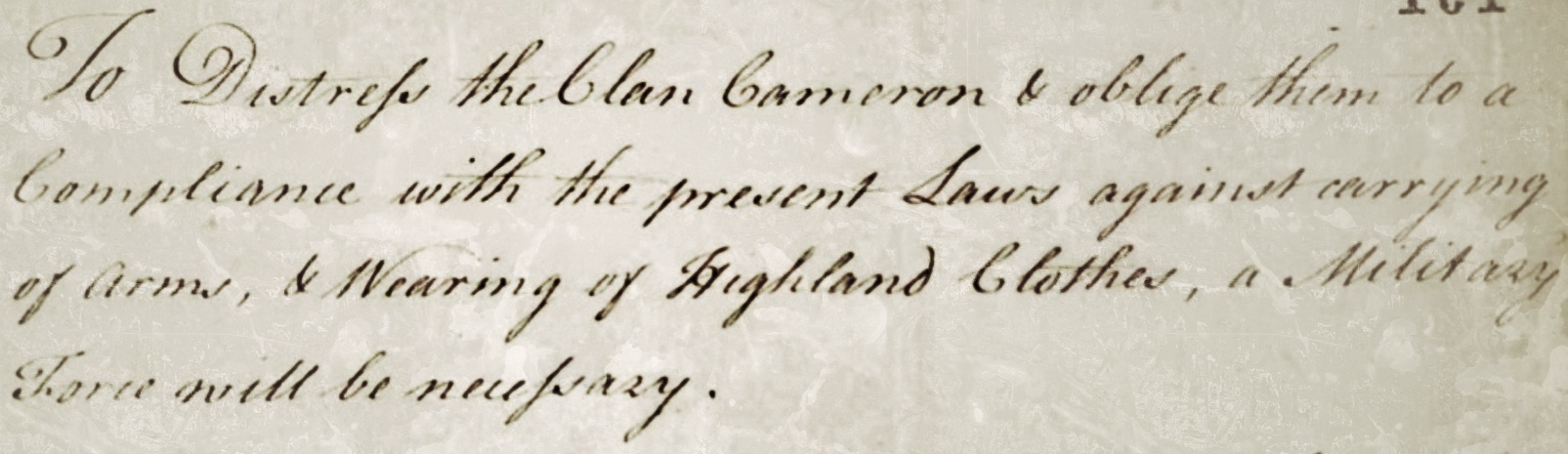

Access and control were collectively the name of the government’s game in eighteenth century Scotland. The Western Highlands bore the brunt of unconscionable retaliation and enforcement after Culloden not because it provided the largest number of rebels who bore arms (it did not), but because it was so difficult to regulate due to the remoteness of its communities and the severity of its weather and terrain. While the isolated villages and steadings in many regions of the Highlands provided distance and shelter for their occupants, that same isolation also enabled heritable chiefs to maintain control of their clans with little interference, as well as allowing currents of Catholicism to endure within a rapidly reforming Scottish populace.3 ‘The old way of life’ may have been desirable for some heritors, but plenty of others were progressive improvers with interests in both imperial ventures and global mercantile investments.4 This alone adequately disproves the popular myth that the Forty-five was a conflict of atavism versus progress.