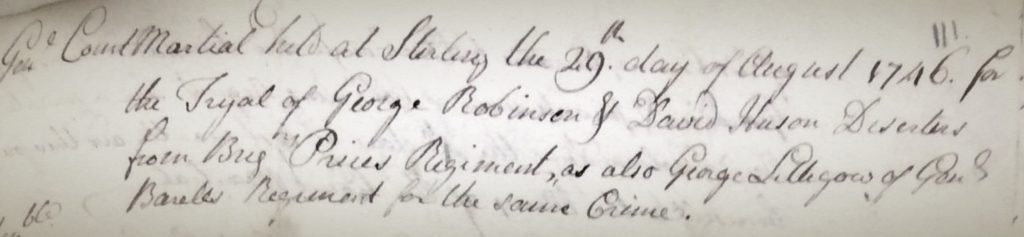

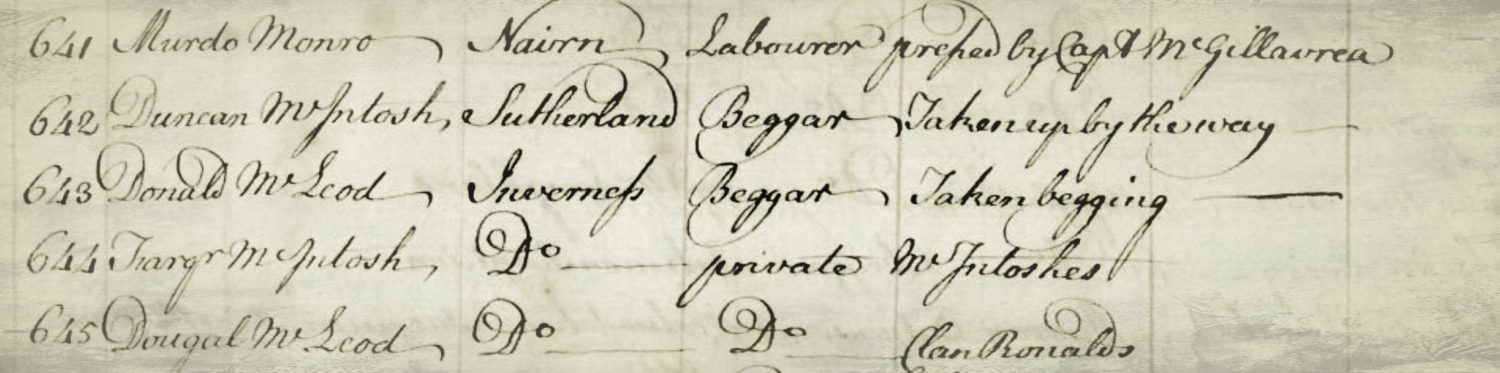

Amidst the complexities of dynastic opposition and civil war during the later Jacobite era, the loyalties and material commitment of individuals were often in flux and have not always been so simple for historians to cleanly define. Allegations of significant Jacobite desertions have long been suspected (and more recently have been examined), but little scholarly enquiry has been made into cases of defection by soldiers within the government forces who were charged with quelling the Jacobite threat in Britain during the ’45.1 Resistance to martial service permeated both sides of the conflict, but deserting ranks to avoid combat is one thing, while joining up with the enemy is another entirely. Archival evidence shows us that soldiers in British service – including loyalist Highlanders on campaign in Scotland – deserted their units in smaller numbers than their Jacobite rivals, but incidents of soldiers breaking ranks was still a problematic issue for British army officers and Hanoverian officials.2 Digging deeper into the sources further reveals that some of these deserters found both cause and motivation to fight amidst the ranks of Jacobite rebels.

Category: Analysis (page 1 of 5)

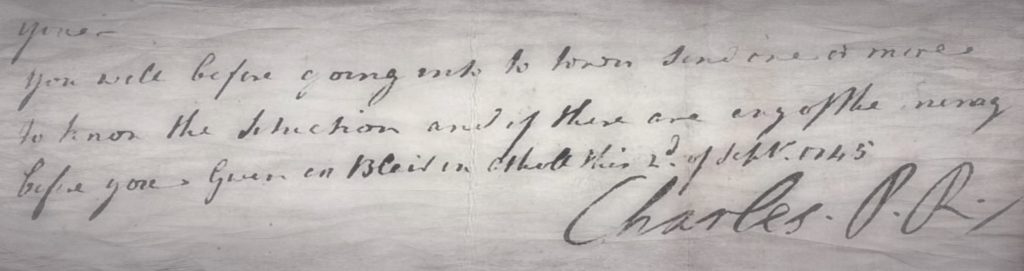

Depending upon which contemporary account one reads, descriptions of the Jacobite army’s behaviour during the 1745 rising can paint a number of strikingly different pictures. Embellished narratives and biased propaganda on both sides of the conflict alternately portray Bonnie Prince Charlie’s troops as infantophagic savages who carved a trail of rapine and destruction through Britain, and a benevolent cadre of altruistic revolutionaries who only took what was freely given, while charming inhabitants in both village and burgh. The reality is, of course, somewhere in between, and eyewitness descriptions provide some validation to both characterisations, which are slanted according to who is telling the story.1 Less commonly explored, however, are the operational accounts of how the Jacobite army conducted itself administratively as it moved through towns in Scotland, solidifying control of ‘North Britain’ in the early months of the last rising. Some of these records, which feature guidelines and orders from Charles Edward Stuart himself about how to orchestrate an occupation, lie in numerous London archives amongst swathes of captured and intercepted Jacobite correspondence.

© 2025 Little Rebellions

Modified Hemingway theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑