The collective social power and reach of the parish minsters in the Presbyterian Church of Scotland was one of the British government’s most potent weapons in quelling the last Jacobite rising.1 These ministers, in addition to being sanctioned recipients for the submission of illegal arms and an integral part of the extensive information network employed to identify alleged rebels, were some of the only people in Scotland that some prominent members of the military felt they could trust.2 Alexander Melville, 5th Earl of Leven, who was High Commissioner of the General Assembly during the Forty-five, remarked to Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle and Secretary of State, at the end of May 1746 that the loyalty of the Scots clergy was exemplary, and despite ‘the smooth arts of flattery & cajoling’ used by the Jacobites to gain their trust, only two specific ministers were known to have any sensitivities to the cause.3

Presbyterian ministers were used to provide intelligence on the whereabouts of the Jacobite army soon after it started to coalesce in August 1745, collaboratively functioning as an essential web of surveillance that tracked every move the rebels made through their entire campaign.4 They raised significant bands of volunteer militias at the request of the government and local heritors, and they provided eyewitness information against suspected civilians and regional officials alike, especially in traditional areas of high-profile Jacobitism like Brechin and Aberdeen.5 The Reverend George Aitken enthusiastically advised government administrators on the spring magistracy elections in Montrose, tapping those with ‘zeal and attachment’ to George II while conversely calling out those of ‘suspicious character’.6 John Jardine, the minister of Liberton parish in Edinburgh, directly (and clandestinely) reported to the Lord Justice Clerk Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun about Jacobite activities in and around Carlisle. From Kintore, Alexander Gordon briefed the duke of Cumberland’s secretary, Everard Fawkener, on a wealth of information from Aberdeenshire collected by his ‘chain’ of clergy strung across the parishes of Forbes, Tullynessle, Clatt, Strathdon, Rayne, and Culsalmond.7 These ministers and many others throughout Scotland worked together within a formalised scheme of relaying external intelligence, overseeing an intricate network of spies who were paid by the government to infiltrate Jacobite army units.8

Some of these well-affected clergymen involved themselves directly on the front lines of the rising, whether that be interceding to discourage Jacobite recruitment efforts from the pulpit or, however rare, actively taking up arms themselves. Prominent rebel officers complained of ‘vile and malicious behaviour’ by the ministers in Strathbogie, and in Arbroath the clergy were so ‘remarkably active in dissuading their parishioners from joining in Rebellion’ that Jacobite soldiers there drew up plans to seize and detain several members of the presbytery.9 Aberdeenshire minister John Bisset recorded in his diary a few days after the Battle of Falkirk that eight Presbyterian clerics had been killed in the action and that the bodies, like those holy men who fell at Inverurie before them, would surely be left unburied by the Jacobite victors and exposed to dogs, ‘the fashion in France with the dead Protestants’. Patrick Simpson, minister of the gospel at Fala and Soutra who was captured at Falkirk, later made his escape from the rebels and went on to inform against a British dragoon officer thought to be conspiring with high-ranking Jacobites.10

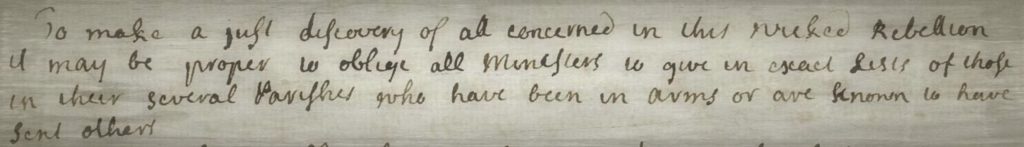

Soon after the fighting had ended and attentions were turned to finding and prosecuting those involved in the rising, Hanoverian officials cleverly demanded that their network of Presbyterian ministers make up lists of all of their parishioners who were not concerned in the rebellion. Fletcher of Saltoun wanted proof of everyone who was innocent, rather than guilty, as well as reports of any preaching discovered in non-juring congregations, whether it be public or private. In theory, this tactic allowed the government to be far less discriminating with its arrests and to open the parameters of prosecution considerably. Counting on the fact that the clergy would likely know most faces in their own parishes, the Lord Justice Clerk sent directives to his sheriff officers throughout Scotland on 30 May 1746 to put this plan into play, and shortly thereafter the sheriffs forwarded these demands to the ministers under their jurisdictions.11

Two sealed copies of each list were required: one to be sent to Fletcher and the other to be delivered Cumberland via Everard Fawkener. Most of the prominent ministers complied, and many of their records are still preserved within Fletcher’s and Cumberland’s archival papers. Responses were returned by clergy from every county in Scotland, from Ayrshire to the northernmost parishes in Orkney, all in varying states of exactness. While some determined ministers carefully took stock of the many hundreds of their parishioners, transcribing each of their names in lengthy rosters and organising them by their landholding status, others were convinced that not a single resident in their districts were involved in the rising, and accordingly they submitted no lists. In Haddington, Patrick Wilkie claimed that out of 3000 ‘examinable persons’ in his parish, two-thirds were his own hearers and none of them were disloyal to the government. In the Midlothian parish of Currie, minister of the gospel David Moubray wrote to Fawkener that of 1000 parishioners, only one was known to be directly involved with the Jacobites.12

Feeling that the Lord Justice Clerk’s scheme was perhaps not entirely fair to many potential innocents regardless of their faith, some ministers expressed dismay at the implied persecution of their fellow Christians. Lauchlan Shaw in Elgin affirmed that despite the government’s attempts to equate all non-jurors with Jacobites, he had not had access to any Episcopal meeting-houses in the area

to know their conduct, which we have had with respect to our own people. It cannot be justly inferred, that all who are not in our lists are guilty; the natural inference from it is, that we are not proper judges of the moral conduct of those who do not submit to our ministry.13

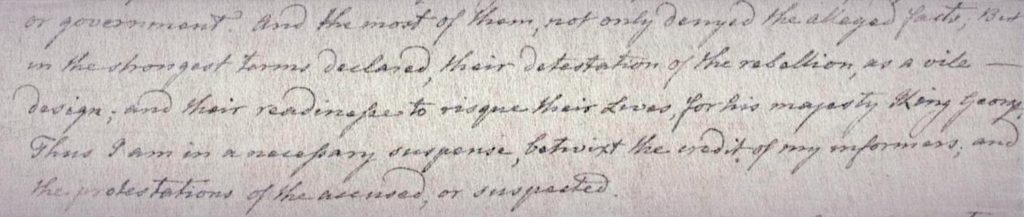

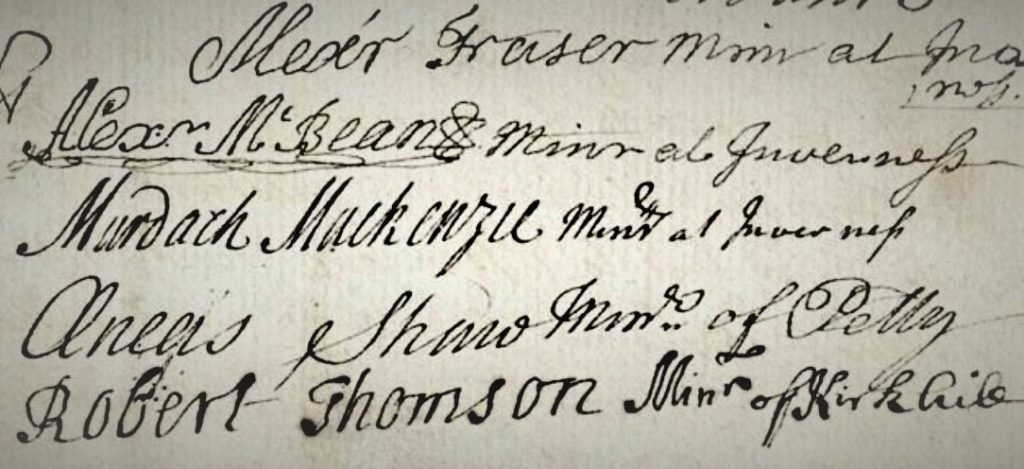

A consortium of seven clergymen in Inverness-shire likewise balked at the directive, noting a number of flaws in the plan’s integrity. They cited the goodwill they had long engendered within their respective communities, and in fact it was that very goodwill that frustrated Jacobite recruiters as they tried to raise soldiers during the campaign. The Inverness clergy insisted that any lists they created would be imperfect, especially considering that many parish ministers were forced to flee their posts during the rebel occupation of their church lands, and they were therefore out of contact with a significant number of their parishioners through the conflict.14

The Reverend John Warden in the Stirlingshire parish of Campsie responded to the government’s demand with a syllogistic refusal on the grounds that of the 1400 souls under his purview, only a dozen were even suspected of any Jacobite sympathies. Of those suspected, Warden asserted that he had no way to confirm they either were or were not concerned, and their respective absence from or presence within the list would necessarily imply biased guilt or innocence. Furthermore, Warden posited, the suspected actions were all borne of ‘private whispers’ and could not have been proven with material evidence.15 On behalf of the Edinburgh ministers, Hugh Blair wrote a similar response to Fawkener, stating that it was impracticable to comply with such a directive, believing it a task more suited to proper law enforcement. Fearing that subjectively identifying loyal parishioners might ‘screen rather than discover the Guilty’, Blair assured the secretary that their presbytery’s refusal should not be mistaken for sympathy to a cause ‘whose pernicious Schemes we resolve thro’ Divine Grace to resist even unto Blood’.16

Nine ministers from the presbytery of Dalkeith were also uncomfortable enough with this task to proclaim that despite their ‘undecaying Zeal for the Protestant Religion and British Liberty’, they were concerned that compliance would cast the Scottish people ‘in too undistinguished a light’. Moreover, they warned, the assignment was a dangerous one that could undermine the influence of the Established Church and play directly into the hands of its Jacobite enemies; convicting those who might be innocent by omitting them from their lists would be ‘Treachery to our Duty’, they wrote, and some with authentic Jacobite sympathies could simply practice ‘the vile Art of lying conceal’d under the detestable Cover of public Protestations and Solemn Oaths’. Dalkeith would not and could not in good faith abide by the government’s orders.17

Fawkener appears to have conveyed these protestations to Cumberland shortly after their receipt, and though it remains to be seen if there were any consequences for the clergy who refused to aid in the scheme, a response from the secretary provides some insight into his temperament. To the Edinburgh minister William Wishart, Fawkener revealed that the point of posing such a significant ask was not meant to cause any difficulty, but rather was created with a view ‘to procure some Light into this detestable Scene of Confusion’. He cautioned against the seduction of pity for Wishart’s parishioners, warning that ‘it almost always happens that an ill judged Lenity is the greatest Cruelty’. Yet without explicitly ordering Wishart to produce his list of hearers, Fawkener made it quite clear that he had expected each and every minister of the gospel, as loyal servants of the government, would ‘be pleased to put his Sickle into so fair a Harvest’.18

It is unclear how valuable the transmission of parish registers were for government prosecutors in locating and rounding up suspected Jacobites, especially when compared to the vast corpus of material in circulation about the many thousands who were known to have actively participated in the final rising. Church of Scotland ministers also contributed to writing up rosters of the suspected and the guilty, but most of these reports were overseen by local justices of the peace and commissioners of excise who were stationed at strategic points across Scotland. There is no compelling judicial evidence that Hanoverian officials ever used the Lord Justice Clerk’s collection of parish lists to determine who not to prosecute. Yet they provide a useful glimpse into granular populations and landholding structures across disparate areas of the nation, and could well have been used to calculate the organisation and reach of heritable jurisdictions during the dusk of the Jacobite era – just before those traditional powers were removed by Act of Parliament in 1748.19

This article first appeared in the Nov/Dec digital content of History Scotland (Vol. 21 No. 6)

as part of its regular Spotlight: Jacobites column.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people who were involved in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the protean nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and accessible research.

That so many Presbyterian ministers were ready and willing to serve as agents of the state is pretty disappointing. Very much love to talk with you about this sometime, Darren.

The Church of Scotland was the official confessional institution for the post-Revolution British government north of the border, and it functioned in a similar manner from the opposite side of regnal power during the Covenanting era. Obviously this was before the French and American Revolutions and the global wave of resistance to church and state speaking with one voice. Putting aside our modern lens, the involvement of CoS ministers in anti-Jacobite intrigue was the very opposite of disappointing for a large majority of the Scottish populace, as they were so central to their parishioners’ lives and wielded so much power… Read more »

Thank you, these articles are a fascinating read. I always felt sure there had to be more to the Jacobite narrative.

And can see there is much more yet to be revealed..

Appreciate your time and interest, Mims. Yes, our understanding of the period and the people who inhabited it is constantly increasing. The discipline is in a positive state just now!