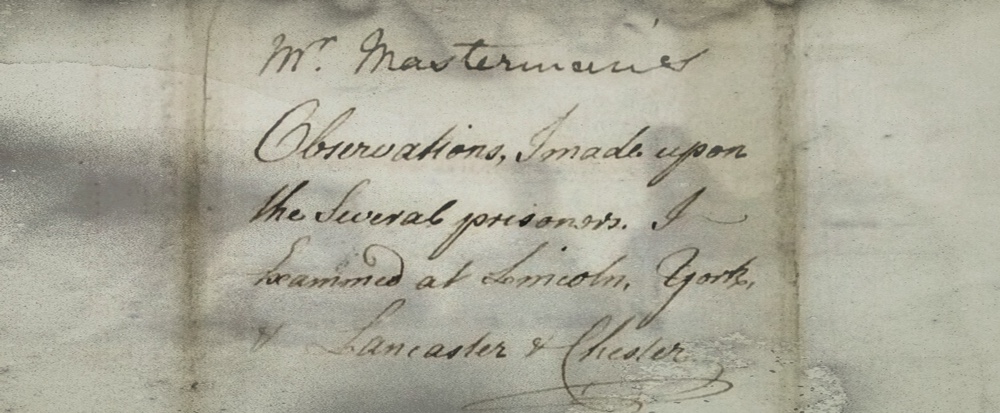

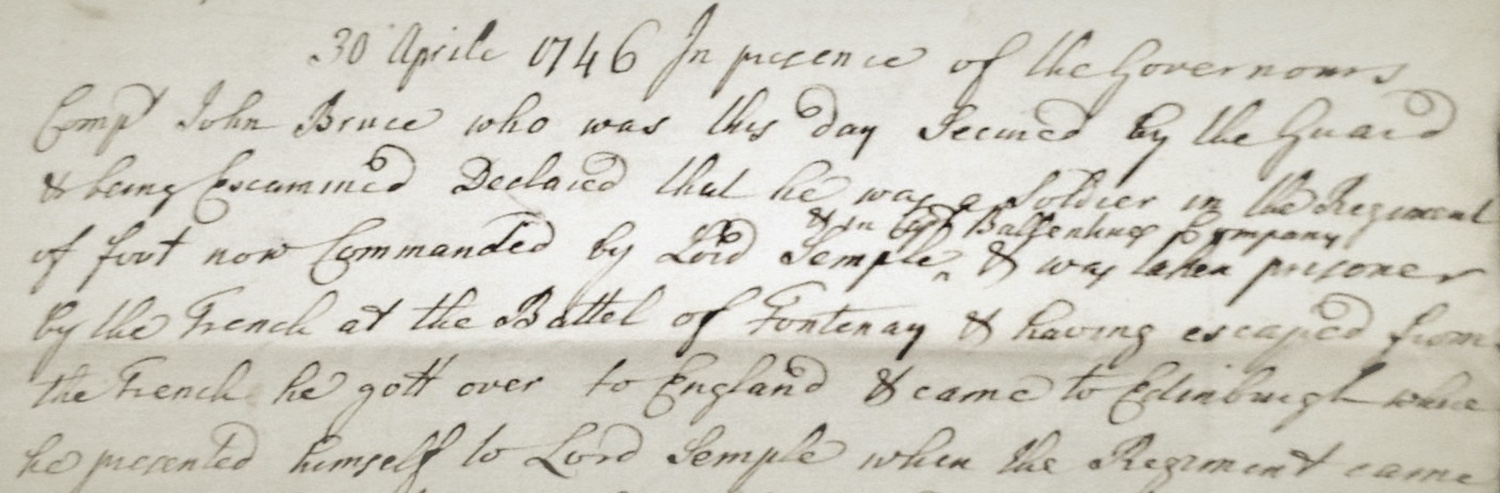

In the spring of 1746 on a journey that lasted over two months, Henry Masterman and his clerk, Richard Wright, visited a number of jails in Lancaster, Chester, York, Lincoln, and London. There, these men interviewed Jacobite prisoners and took notes on their characters to assess their level of guilt and their willingness to testify against fellow inmates as witnesses for the Crown.1 Masterman was known for his experience with criminal prosecutions and for his great ‘fidelity’ to the government, borne out through his service in a similar capacity in the wake of the 1715 rising.2 Thirty years later he was once again asked to determine in what ways these suspects were involved in the Forty-five, including those who had ‘in any way fomented and encouraged it, as [well as] those who were actually in arms’.3 Masterman’s letters recount a tedious process fraught with the intransigence and dishonesty of many of the captives, in some places around half of which required a translator who could understand the language ‘universally Spoke in much ye greatest part of ye Highlands’.4

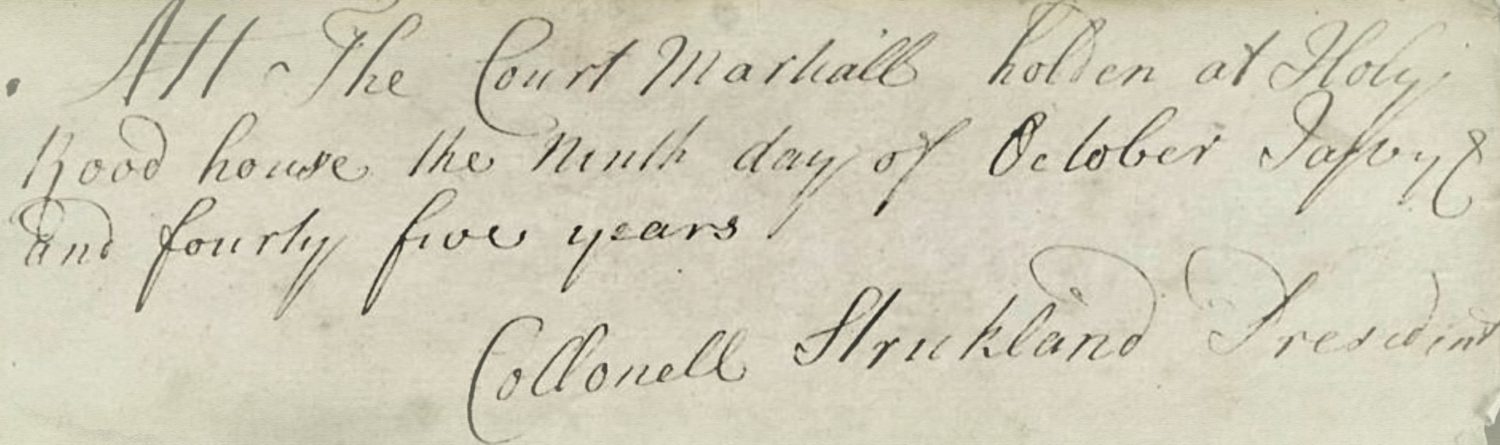

By the beginning of the new year in 1746, the British government once again found itself deeply mired in a civil war, as what would prove to be the final Jacobite challenge played itself out across Scotland and England, with France seemingly waiting in the wings. The Jacobite army had only recently recrossed the Scottish border after turning back at Derby, and just four months later its martial campaign would be ruthlessly crushed by British forces under William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland, on Culloden Moor in the Highlands of Inverness-shire. Even in the midst of the crisis while both armies were still in the field, many hundreds of alleged Jacobite soldiers and civilians who were captured in the preceding months were already being examined and processed by agents within the Hanoverian government. After over half a century of dynastic and political contention that repeatedly manifested in clandestine plots and active Jacobite risings, these agents were sharply focused on creating a plan to punish treasonous activity that would ensure this was the very last time they would have use for one.5