Much of the enduring memory and emotion of the final, failed Jacobite challenge blooms from the British government’s retributive and bloody response in the aftermath of Culloden. In what Allan Macinnes calls the ‘exemplary civilizing’ of remote areas of Scotland, a calculated campaign of violent suppression was waged upon recalcitrant communities whether or not they were directly involved in active rebellion.1 Whether tantamount to genocide, as some scholars have argued, the cantonment schemes established in Culloden’s wake and the retaliatory expeditions against communities singled out by government intelligence networks undeniably had a disastrous effect upon ‘Scottish Highland’ culture, though these depredations were not by any means meted out only in the Highlands.

Category: Vignettes (page 4 of 6)

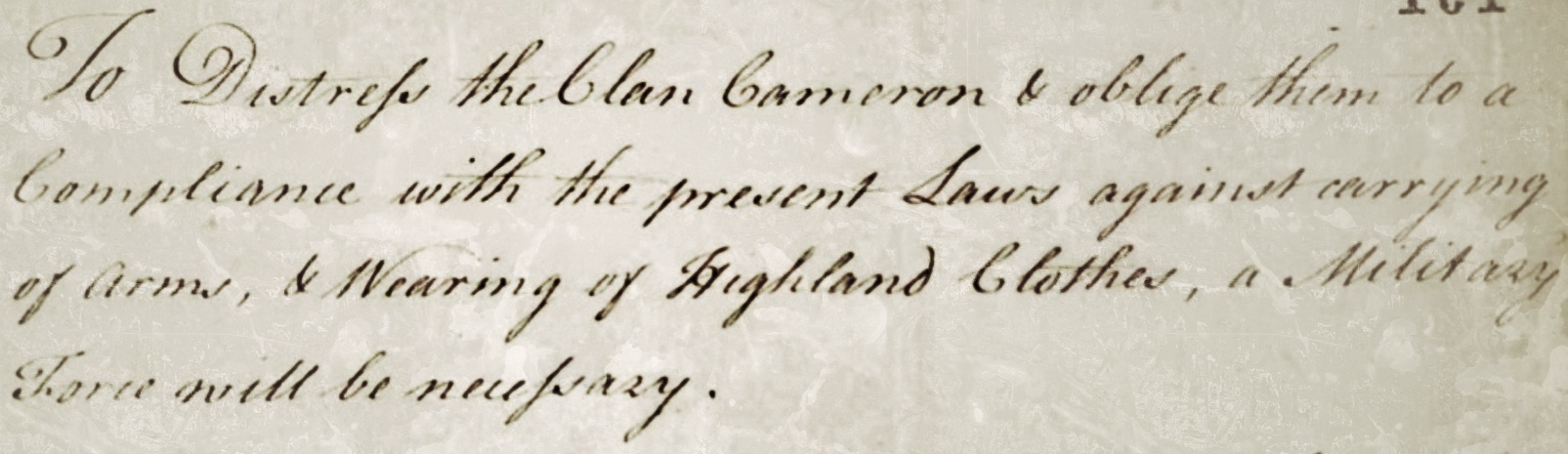

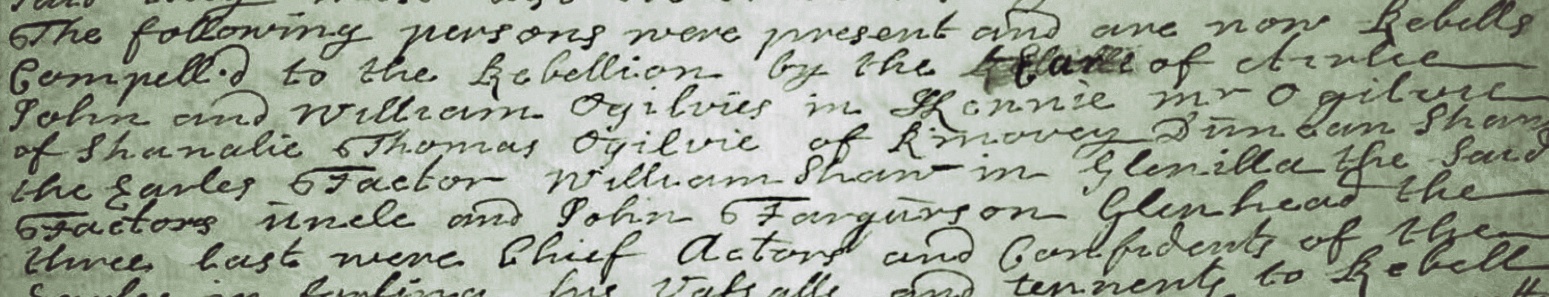

In early December 1746, well after the active threat of the last Jacobite rising had waned, the British government was still collecting intelligence regarding known rebels who had not yet been apprehended. The report of Alexander Robertson of Straloch from that month, presumably sent to the Duke of Newcastle, is especially interesting for two specific reasons. First, it explicitly calls out the forceful tactics of impressment used against unwilling tenants on David Ogilvy, 6th Lord Arlie’s estate. Second, within it Straloch proposes an elaborate plan to trick lurking Jacobites into revealing themselves – a plan that is both impressively calculated and devious.1

Known informally as Baron Reid, Alexander Robertson of Straloch was a gentleman from the Strathardle area of Perthshire whose family had long been aligned with the house of Argyll and the Hanoverian government. He was a vassal of James Murray, the loyalist Duke of Atholl, and he spent much of the rising assisting the government by providing intelligence reports and offering counsel regarding methods to suppress the rebels.2 Straloch was evidently quite well connected during the Forty-five, corresponding directly with Newcastle – the secretary of George II – and Duncan Forbes of Culloden, the Lord President of the Court of Session. To these officials he sent a series of bulletins between 1745 and 1747 leveraged from the network of Presbyterian ministers in Perthshire and the north-east who received and conveyed useful intelligence about Jacobite movements.3 Straloch was effective enough as an informant to warrant a mandate for capture from Atholl’s brother William, the Marquess of Tullibardine and titular Jacobite Duke of Atholl.4

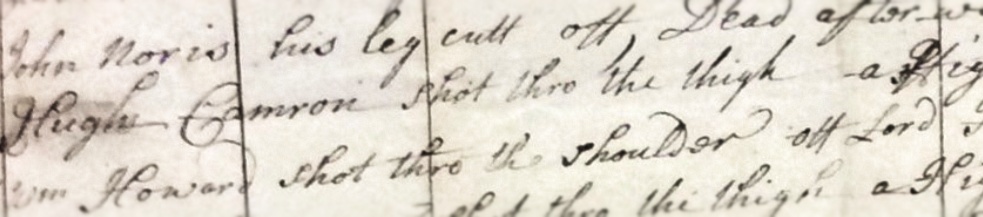

Though it is easy to get lost in the romantic historical record of a conflict like the Jacobite risings, occasionally a document comes to light that viscerally describes the dreadful effects of civil war from a time long past. Jail returns like this one, which registers some of the sick and wounded who were confined in Stirling Castle during the spring of 1746, tell us a number of things about the cost of battle in eighteenth-century Britain – both literally and figuratively. This particular return from the National Library of Scotland lists the names and conditions of twenty-six men held at the castle and treated by the doctor there, and some of the language used to describe the wounds of these men truly brings the past alive in a horrific manner.1

Not all of these prisoners were Jacobite soldiers. Only six on the list are specifically noted as ‘rebels’, though three others are recorded as having been in league with Lord John Drummond’s troops in French service, who came to Scotland in the winter of 1745 to fight in the Jacobite army. A further three individuals are simply described as ‘Highland men’, but the implication is that they were also in prison for treasonable acts. At least two of the men appear to be deserters from British army regiments, and the other dozen are not identified by their crimes. Nonetheless, the grisly conditions recorded about many of these prisoners tell of their adversity.

© 2024 Little Rebellions

Modified Hemingway theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑