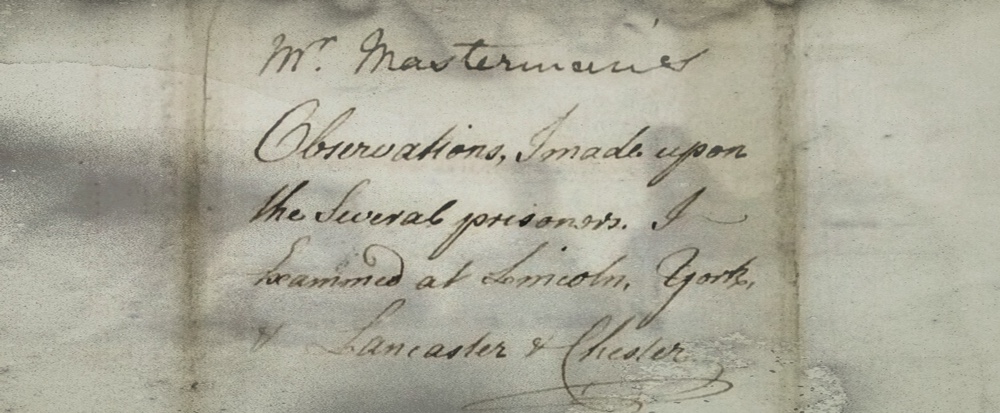

In the spring of 1746 on a journey that lasted over two months, Henry Masterman and his clerk, Richard Wright, visited a number of jails in Lancaster, Chester, York, Lincoln, and London. There, these men interviewed Jacobite prisoners and took notes on their characters to assess their level of guilt and their willingness to testify against fellow inmates as witnesses for the Crown.1 Masterman was known for his experience with criminal prosecutions and for his great ‘fidelity’ to the government, borne out through his service in a similar capacity in the wake of the 1715 rising.2 Thirty years later he was once again asked to determine in what ways these suspects were involved in the Forty-five, including those who had ‘in any way fomented and encouraged it, as [well as] those who were actually in arms’.3 Masterman’s letters recount a tedious process fraught with the intransigence and dishonesty of many of the captives, in some places around half of which required a translator who could understand the language ‘universally Spoke in much ye greatest part of ye Highlands’.4

By the beginning of the new year in 1746, the British government once again found itself deeply mired in a civil war, as what would prove to be the final Jacobite challenge played itself out across Scotland and England, with France seemingly waiting in the wings. The Jacobite army had only recently recrossed the Scottish border after turning back at Derby, and just four months later its martial campaign would be ruthlessly crushed by British forces under William Augustus, the Duke of Cumberland, on Culloden Moor in the Highlands of Inverness-shire. Even in the midst of the crisis while both armies were still in the field, many hundreds of alleged Jacobite soldiers and civilians who were captured in the preceding months were already being examined and processed by agents within the Hanoverian government. After over half a century of dynastic and political contention that repeatedly manifested in clandestine plots and active Jacobite risings, these agents were sharply focused on creating a plan to punish treasonous activity that would ensure this was the very last time they would have use for one.5

Calling upon persons of exceptional experience and dedication to the Whig administration of George II, government ministers constructed an intricate system of information-gathering to catalogue and evaluate the deluge of suspected and accused Jacobite rebels who were being held in prisons on both sides of the border. Gaols and tolbooths alike were packed to the walls with incarcerated citizens of Scotland, England, Ireland, and France who had either been taken in arms or who had aided Jacobite schemes through non-martial actions. A significant number of prisoners were taken in on suspicion alone, preliminarily and without any compelling material evidence of their wrongdoing.6 Government policy was focused upon controlling the rising as quickly as possible, as evidenced by its suspension of habeas corpus on 18 October 1745, which eased restrictions on unlawful imprisonment. Other Parliamentary Acts followed, allowing authorities to try those accused of treason in a place of the king’s choosing rather than in the county where the alleged crime had occurred.7 As a direct result of these statutes, all Jacobite trials were conducted in England rather than in Scotland.

The prisons continued to fill even as the rising persisted, and the government’s need to process and punish the surfeit of inmates quickly took precedence in its agenda. Reliable delegates were hired and sent to numerous towns and burghs across Britain to examine prisoners and to assess their potential for trial. David Bruce, Judge Advocate of the King’s Army, was dispatched to Scotland to prepare lists of suspects and to perform pre-trial examinations, or precognitions, of prisoners in order to begin the legal process against them.8 Henry Masterman, who served as Crown Clerk to the Court of King’s Bench, was sent to numerous English towns where Jacobites were being held in order to document enough evidence to bring suitable charges. Commissioned on 11 March 1746 by Thomas Pelham-Holles, Duke of Newcastle and Secretary of State to George II, Masterman was tasked with leading the enquiry into the circumstances of Jacobite participation with the help of other ‘Gentlemen of the Country’ known for their extraordinary ‘Zeal for His Majesty’s Service’. His collected information would be the starting point of continued prosecution by the Attorney General, Sir Dudley Ryder.

By the end of April, Masterman had completed his enquiries at Lancaster, where many of the soldiers from the Jacobite Manchester Regiment were confined after its capture at Carlisle. Masterman reported to Newcastle that most of these men were Roman Catholics and ‘are a Set of ye most hardned Wretches I ever met with; They seemed to be all agreed, except about three or four of them, to answer every individual Question negatively…’ and he suggested they were instructed to do so by the ‘very artful’ Nicholas Skelton, a Catholic priest also in custody there.9 Masterman was nonetheless able to conduct 140 examinations at Lancaster, determining that seventeen of the prisoners could be made into witnesses. His notes mark the men who ‘gave a very fair account’ and whom he believed to be truthful. One soldier named William McGee, ‘a very Honest Old Man’ who served in the Duke of Perth’s regiment, agreed to turn evidence but asked Masterman not to tell the other prisoners ‘for fear of being Murdered’.10

Clerk Masterman confided to Newcastle that he had great difficulty with Thomas Coppock, the Jacobite ‘Bishop of Carlisle’, who sat for him a number of times at Lancaster and refused to submit to examination unless he was assured of receiving the king’s pardon for doing so. Coppock further attempted to haggle with Masterman and even suggested settling for transportation, but in the end he agreed to sign off on his testimony with no assurance of clemency, as the clerk simply did not have the powers to negotiate such an arrangement. Coppock, who Masterman thought had harboured many ‘secrets’ of the rebel chiefs, would be sentenced to death and executed on Harraby Hill in Carlisle on 18 October 1746, a Market Day for the town.11

On 4 May, Masterman’s assistant Richard Wright wrote to Treasury Solicitor John Sharpe from Chester with news that they had been delayed by illness, but they still managed to get through their queue of 124 prisoners at Chester Castle by the 13th.12 Masterman’s experiences there were more favourable, and he describes the people in Chester as ‘much more open and candid than at Lancaster’, but that they were ‘a poor Stupid ignorant set of Wretches; have told all they know, but there are very few Genius’s Amongst them’ and therefore not many were thought suitable to be witnesses. Yet thirty-eight prisoners at Chester were chosen by the clerks to provide evidence against their fellows, the highest number established at any of their stops.13

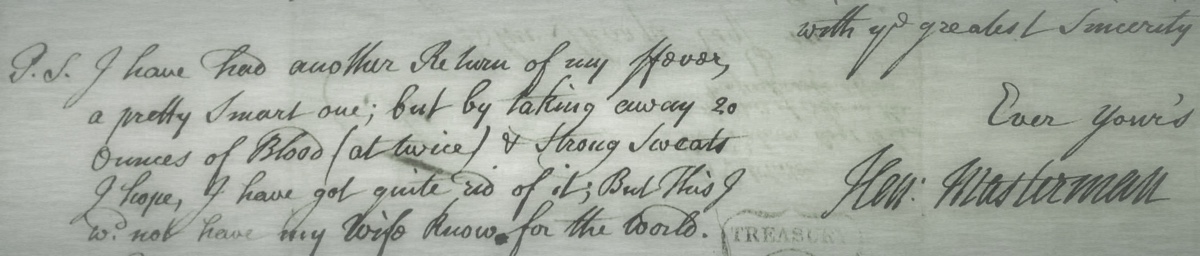

I have had another Return of my fever, a pretty Smart one; but by taking away 20 Ounces of Blood (at twice) & Strong Sweats I hope, I have got quite rid of it; But This I wd not have my Wife know for the World.14

From the Chester examinations, Masterman determined that most of the captives were under some sort of compulsion, being ‘forced in by their respective Chiefs’ and purposefully left at Carlisle because they were not ‘Steady fellows’. This fact, he relayed to Sharpe, was not lost on the prisoners, who were fully aware they were left as a sacrifice, which ‘has enraged them all extremly agt their Principals’. This was not the first time that the Jacobite order to leave the Carlisle garrison behind was posited as a sacrifice, as Lord George Murray himself considered the town to be untenable and explicitly took Charles Edward Stuart to task for the needless waste of life and resources.15 Masterman’s assessment, however, does appear to provide a remarkable insight into the collective feelings of the garrison itself. If his allegation of purposeful abandonment is accurate, it has the potential to reframe our understanding of how the upper echelon of the Jacobite command prioritised and used its manpower, as well as illustrating a poignant motive behind Murray’s obstinate insistence on establishing a regimented council of war.

By the middle of spring 1746, the investigation circuit was completed, and Masterman petitioned the Commissioners of the Treasury on 7 August for services rendered from 13 March to 19 May. During this period he took in 467 examinations, which he proudly boasted ‘laid the foundation for most of the present Prosecutions for High Treason’. Along the way, Masterman lost his favourite servant, who fell ill and and was left behind ‘in his last agonies’ at York, presumably from gaol distemper contracted from the many wretched prisoners held there in horrific conditions. Henry Masterman asked to be compensated for costs connected to both his and Wright’s service, including the risks to his health and damages caused by being absent from his business, and the Treasury approved a payment of £300 on 2 October.16 Treasury Solicitor Sharpe estimated that 151 (32%) of these cases had sufficient evidence (in this sense meaning more than one witness) against them to be tried, though this was but an early round of gathering information toward prosecution of the last Jacobite rising, and many more would be added to the government’s docket in the following months.17

This article first appeared in the March/April digital content of History Scotland (Vol. 21 No. 2)

as part of its regular Spotlight: Jacobites column.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people who were involved in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the protean nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and accessible research.