Depending upon which contemporary account one reads, descriptions of the Jacobite army’s behaviour during the 1745 rising can paint a number of strikingly different pictures. Embellished narratives and biased propaganda on both sides of the conflict alternately portray Bonnie Prince Charlie’s troops as infantophagic savages who carved a trail of rapine and destruction through Britain, and a benevolent cadre of altruistic revolutionaries who only took what was freely given, while charming inhabitants in both village and burgh. The reality is, of course, somewhere in between, and eyewitness descriptions provide some validation to both characterisations, which are slanted according to who is telling the story.1 Less commonly explored, however, are the operational accounts of how the Jacobite army conducted itself administratively as it moved through towns in Scotland, solidifying control of ‘North Britain’ in the early months of the last rising. Some of these records, which feature guidelines and orders from Charles Edward Stuart himself about how to orchestrate an occupation, lie in numerous London archives amongst swathes of captured and intercepted Jacobite correspondence.

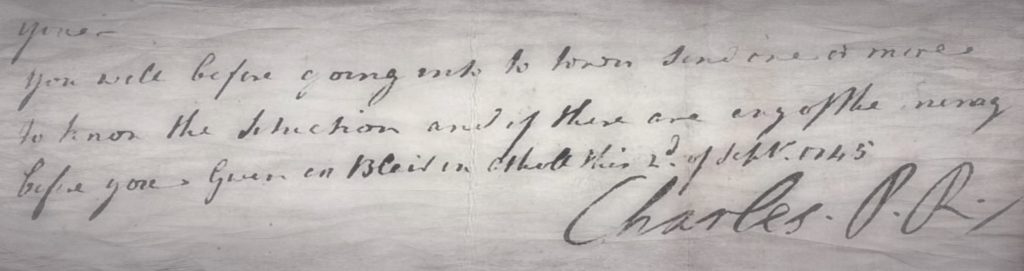

Regardless of how the army actually behaved while on campaign, a selection of these documents shows how Jacobite leaders had planned for a transfer of power on the ground, piece by piece, as they moved from the Western Highlands down through Perthshire and into Edinburgh. The burgh of Perth was the first significant urban centre inhabited by the rebels, and it acted as a sort of proving ground for the military seizure of a civilian hub, but also as a test for how efficiently the army could appoint civic leaders and sustain logistical control of the surrounding region. From his camp at Blair Atholl in early September 1745, Charles Edward penned explicit instructions for Donald Cameron of Lochiel, giving him a list of goals to achieve upon entering Perth and guidelines for how to maintain both martial and governmental jurisdictions. These are perhaps the earliest known written orders of the kind from the Forty-five, and they provide a useful template with which to track the evolution of Charles’ intentions for administrating localised control.2

Within this dispatch, Lochiel is instructed in clear and measured language to first approach the burgh with two-hundred men, sending a couple of scouts ahead ‘to know the Situation and if there are any of the Enemy’ before them. Once inside, he was tasked with immediately gathering up the local officials, including the provost, bailie, and town clerk, and in their presence was to proclaim James Francis Edward Stuart as King James VIII & II at the mercat cross, followed by a public reading of the Stuart manifesto for all of the inhabitants to hear.3 With this accomplished, Cameron was directed to locate Perth’s customs and cess collectors and to seize ‘all the money in their hands’ for the use of the army.4 That the first two goals were focused upon projecting the Jacobites’ dynastic claim and securing funds to fortify the army tells us something about Charles Edward’s priorities, and he would repeat this working pattern as the campaign wore on.

With fresh provisions in-hand, Lochiel would then need to secure the streets of Perth and guard against unwanted incursions from the outside, as well as internal resistance from those who were loyal to the Georgian government. His instructions to this end were to post sentinels upon a number of streets and to commence with searching every house ‘without exception’ for all the arms and ammunition that could be found. Charles insisted that a detailed log should be kept to mark the owners of all seized weapons, with the express purpose of returning them to those who would join the Jacobite army. To prevent British troops from getting too close to their new centre of operations, Lochiel’s final orders were to send a team of spies to watch the enemy’s camp at Stirling, and to report back immediately so any challenging marches could be countered with reinforcements.

When the prince entered Perth two days later, he was greeted by the sound of bells tolled by the hands of one of the town’s barbers, James Bayne.5 Quartermasters like Alexander Smith of Inveramsay in Lord Pitsligo’s cavalry would scout ahead to secure safe lodgings for Jacobite commanders and suitable stables for their horses.6 Only some accounts state that Charles again proclaimed the restoration of his father at the cross shortly after arriving, but most agree that during the next week he oversaw the consolidation of martial forces and appointed numerous high-ranking officers to employ similar principles of engagement and occupation in nearby towns, including Dunkeld and Dundee.7 As would be expected, some public sentiment tended to shift toward the new governours in these places as disaffected citizens felt more comfortable expressing their views. Witnesses would later claim that John Rutherford, a writer and reputed Jacobite, ‘threw off the hats of & insulted some of the Inhabitants, on the open Streets, for not bowing to the Pretender’ as Charles was passing out of Perth on 11 September on his way to take the largest burgh in Scotland.8

The Jacobite army’s entry into Edinburgh in the early morning of 17 September was a more delicate affair until it wasn’t. After a week of tiptoeing around the walls of the capital and preparing for a forceful assault to bring about total capitulation, elements of Lochiel’s advance guard rushed through the eastern gate virtually unopposed. Some controversy surrounds the record about exactly who left the Netherbow port open for such a lightning breach, with more than a few contemporaries on the scene fervently expressing the conviction that it was arranged by the Jacobite-inclined provost, Archibald Stewart.9 Despite never being able to secure the castle, the scheme for Edinburgh’s occupation was similar to the one drawn up for Perth. Burgh officials were immediately gathered up ‘upon pain of high treason’ and by around noon King James was declared at the mercat cross.10 Some 300 soldiers and officers were stationed at the nearby weigh-house to block any news or information from reaching the government’s garrison in the castle. Charles then set to work on gathering up supplies and collecting contributions in the form of taxes from the capital’s citizens – especially the ones who were opposed to Stuart interests.11

From his headquarters at Holyrood House in late October, just before the mainstay of the Jacobite army departed for England, Charles sent orders back to Perth to direct the continued administration of their first urban prize. Addressed to the two main Jacobite governours there, William Drummond, 4th Viscount Strathallan, and the senior Laurence Oliphant of Gask, the prince laid out a clear set of priorities to maintain the status quo while he was on campaign across the border.12 His six-point checklist included directives for stocking the town with a sufficient number of officers and making sure they were paid in a timely fashion. This was followed up with reminders to levy the cess ‘in the most proper method for the good of the Common Cause both in the Civill and Military Government’ and to ensure that the governours demanded contributions from all those ‘who have not Join’d the Standard’. As was the usual practice of Jacobite administrators, the Perth customhouse books were summoned to prove the town’s capacity for payment by its citizens.13 Because a significant number of British army officers were taken prisoner after the Battle of Prestonpans and sent under guard to Perth, Charles insisted that Strathallan and Gask have all of the prisoners check in with them on a weekly basis to ensure they had not broken the terms of their parole.14 Finally, orders were given to keep continued correspondence with ‘the King’s friends every where’ and to carefully tend the extensive intelligence networks that would be necessary for long-term Jacobite success. That this information is derived from intercepted dispatches suggests that the latter was not always a simple thing to manage.

It is abundantly clear from this evidence that intentional, structured plans were made toward establishing provisional governments in Scottish towns and localities, but these were neither sustained nor sufficiently supported when the bulk of the army and its commanders marched south toward London. By around the time they returned after a contentious retreat, many early Jacobite strongholds had either been challenged or lost, and with them the precious supplies and civic support they needed to turn an army of occupation into one of permanent governance. The inability of Jacobite leadership to maintain clean and defensible lines of supply and logistics along the paths that the army marched was one of the most prominent determinants of failure during the last Jacobite rising.

This article first appeared in the May/June 2022 issue of History Scotland (Vol. 22 No. 3)

as part of its regular Spotlight: Jacobites column.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people who were involved in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the protean nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and accessible research.

Fantastic and interesting read, keep up the great work.

Thanks very much for reading and for your kind words, Niall!