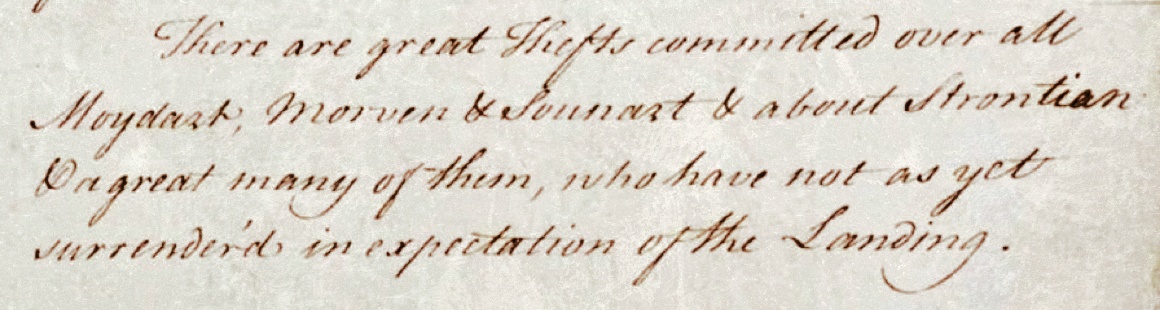

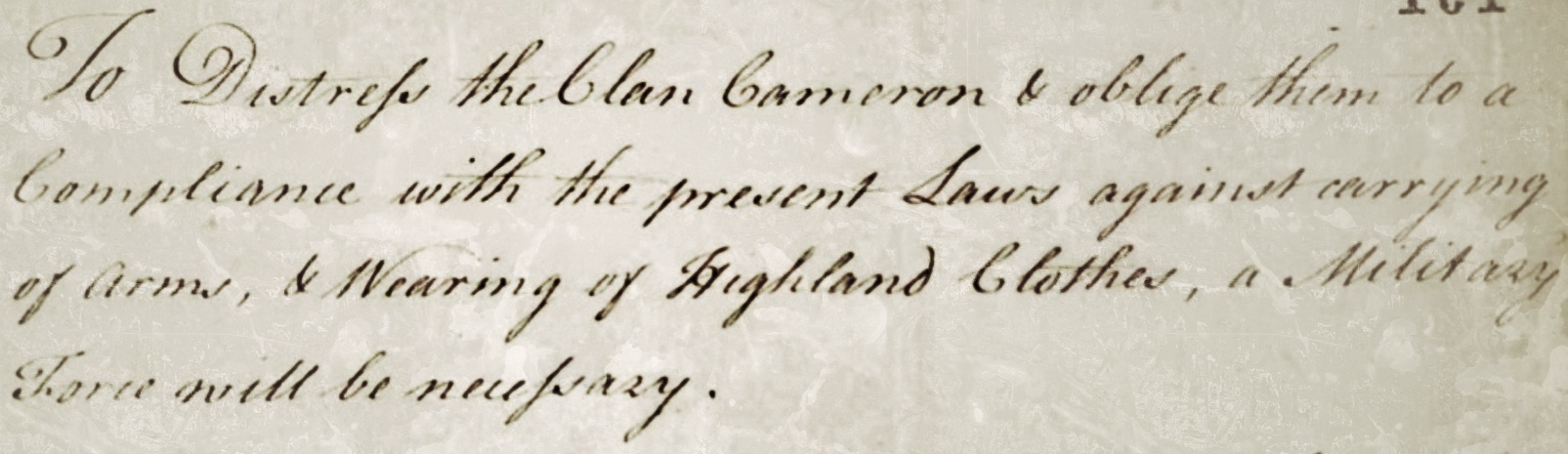

Sometime during or shortly after the Jacobite conflict in 1745-6, a tacksman of the 2nd Duke of Montrose named George Murdoch penned a troubled memorial to his laird. Within this missive, he explains that it would be impossible this year to honor his contract of tenancy, wherein Murdoch was to provide 8000 merks over a period of seven years as rent, capitalized by the cutting and sale of timber from Mugdock Wood in the Stirlingshire parish of Strathblane.1 The problem, he cites, is that the normal operations of business had essentially ground to a standstill on account of disruptive Jacobite activity in the region.

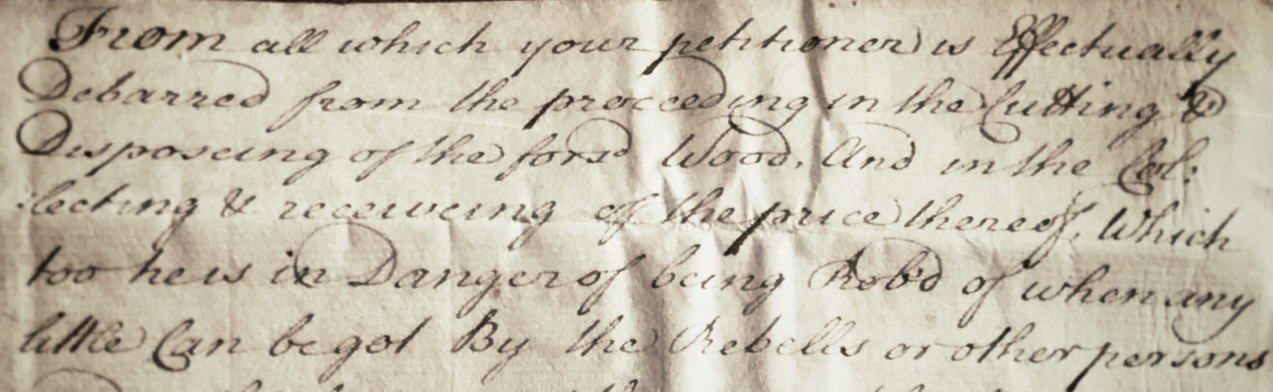

Murdoch’s contract, which had been worked up by Montrose’s factors in February 1744, contained the usual ‘salvo’ or contingency for disasters that might impede the regular course of trade. These included cases of war, pestilence, or famine – the most common uncontrollable misfortunes that could affect the timely payment of rent. The ‘publick calamity’ occasioned by the presence of Jacobite recruiters and soldiers on the loyalist estate of Montrose should be counted among these, claims Murdoch, and he asks for ‘prorogation’ or extension of the contracted time to exclude this unfortunate period of stale business: