Amidst the complexities of dynastic opposition and civil war during the later Jacobite era, the loyalties and material commitment of individuals were often in flux and have not always been so simple for historians to cleanly define. Allegations of significant Jacobite desertions have long been suspected (and more recently have been examined), but little scholarly enquiry has been made into cases of defection by soldiers within the government forces who were charged with quelling the Jacobite threat in Britain during the ’45.1 Resistance to martial service permeated both sides of the conflict, but deserting ranks to avoid combat is one thing, while joining up with the enemy is another entirely. Archival evidence shows us that soldiers in British service – including loyalist Highlanders on campaign in Scotland – deserted their units in smaller numbers than their Jacobite rivals, but incidents of soldiers breaking ranks was still a problematic issue for British army officers and Hanoverian officials.2 Digging deeper into the sources further reveals that some of these deserters found both cause and motivation to fight amidst the ranks of Jacobite rebels.

Occurrences of British army regulars and independent Highland troops under British command choosing to desert and defect to the enemy can generally be explained by overarching cognitive reasons, like crises of ideological, occupational, or moral principles; but also by an individual’s practical concerns, like those of superannuation or lack of pay, familial or agrarian priorities, or feeling that their capture by the Jacobites offered them little other choice. Rebel agents, furthermore, believed that loyalties could be manipulated and encouraged desertion within the King’s troops by promising payment and pardons.3 Examples of all of these are recorded through the rising and demonstrate that revolutionary conflict is a messy business and the battle lines are subject to change along with the personal contexts of the participants.

John McKeek and William McVicar were both soldiers of the independent companies serving the government under Campbells of Cruachan and Carsaig, and they were taken by Jacobite troops at Kinnachan and Blair, respectively. Both pleaded that they joined the rebels ‘because they were like to be starv’d being only allow’d a pound of Meal each & no more a week except one Shilling’. In their examinations at Inveraray, the two soldiers complained of rough treatment digging in the mines at Fort Augustus in service to the Duke of Perth’s regiment. They also called out a British officer taken prisoner from the Earl of Loudoun’s regiment, Lieutenant Hugh McLane, who subsequently enlisted in a Jacobite unit and proceeded to help the rebels to recruit in the Rannoch area.4 Elizabeth Rob deposed that her husband, a sergeant in Lascelles’ Regiment of Foot, was taken prisoner after the Battle of Prestonpans and ‘was perswaded to Enlist with them’ before being hanged at Carlisle after the capitulation of the town to government troops.5 After a stint of only two months, Niccol Whyte also deserted Lascelles’ in May 1744 and joined the Jacobite hussars in November 1745 when they rode through his home near Kincardine. He then left the Jacobite army and tried to re-enlist with the Royal Scots in February 1746, only to be recognised and imprisoned for treason.6

Cope had complained of desertions amongst his men as early as 20 August, just a day after Charles Edward’s standard was raised at Glenfinnan, drawing the pity of Jacobite officers like John Gordon of Avochie, who called Cope’s deteriorating corps ‘the poorest naiked creatures that ever were seen’.7 Many more were captured at Prestonpans and joined the Jacobite army soon afterward, and some of these men marched with the rebels into England and then back to Scotland after their retreat at Derby. By the end of November 1745, Loudoun had embarrassingly lost scores of his men who melted off to their homes, though only some went on to enlist with the enemy.8 Loudoun wrote to the Earl of Sutherland shortly thereafter that ‘tho’ by our lawes there crime is desertion and the punishment is death’, he would accept them back into the regiment without sanction if they would make their way back to camp.9 Allowances for re-enlisting were eventually mandated by the Secretary of War, Lord Holland, on 7 July 1747, including for those who had actively participated in the rebellion, but few known defectors were shown clemency before then.10

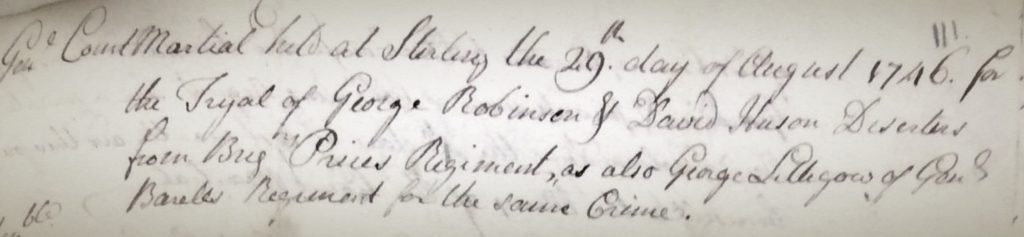

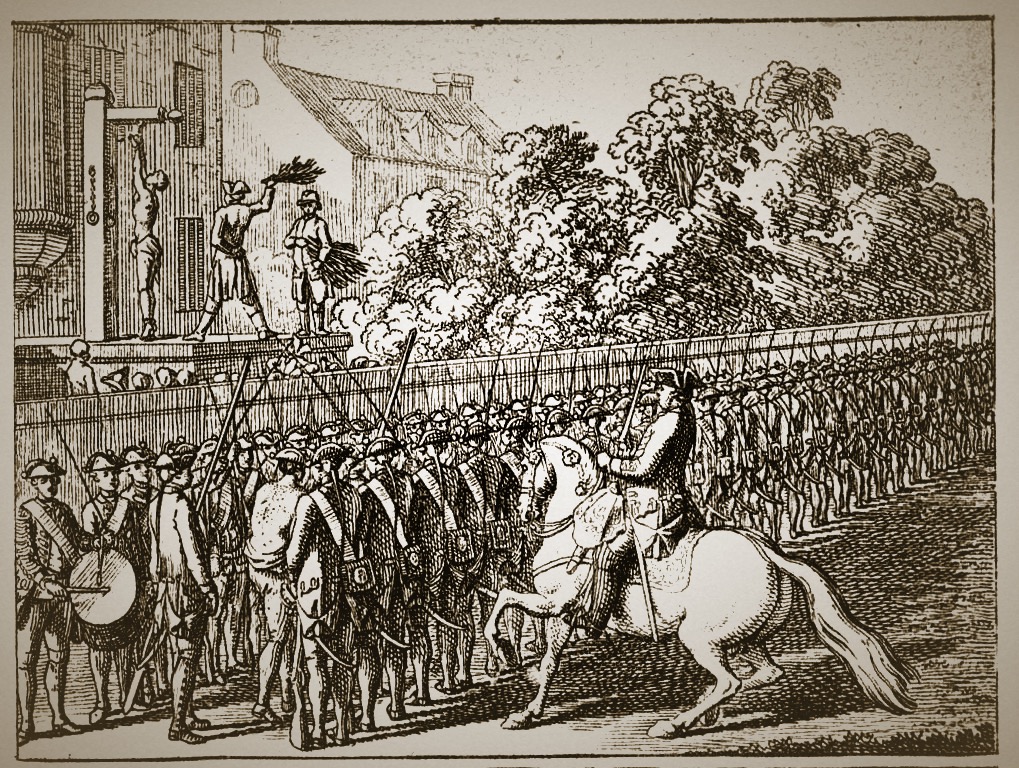

When punishments for desertion were carried out, they were done so in front of the regiment to serve as examples and deterrence, and varied ‘from corporal to capital’.11 Courts martial were held at Perth, Stirling, Inverness, Edinburgh, and Carlisle in the late summer and autumn of 1746. Though they were intended to be conducted within twenty-four hours of confinement, some deserters in Edinburgh were kept in prison for over a month without trial.12 At least forty-eight soldiers in British service were executed after their recapture, usually by hanging ‘with a Libel on each of their breasts’. This number represents a significant proportion of the known deserters and their capital punishment was defined by the charge of treason that came with defection as well as a direct breach of the Articles of War.13 Other deserters were luckier, and a few were pardoned, transported, or even allowed back into their original units, like the eleven men of Guise’s regiment who were given favourable recommendation by a minister in Inverness.14 More often than not, however, soldiers who were proven to have aided or assisted the enemy were condemned to death, regardless of their alibis.

George Lithgow claimed to have been discharged at Ghent after seventeen years as a soldier in Barrell’s 4th Regiment of Foot. He swore upon oath that he was taken up by the Jacobites unwillingly, but Major James Lockhart testified that Lithgow was resentful of the government for his measly outpension after being wounded and that he had taken a commission in Lord Lewis Gordon’s rebel regiment and was no longer ‘one of Geordgs Men’.15 Archibald Henderson of the North British Fusiliers allegedly left his unit after being denied furlough and subsequently enlisted with the rebels, but unluckily he ran into a squad of his fellow redcoats who recognised him and immediately took him prisoner to Edinburgh. One of Lord John Murray’s soldiers, a sergeant named Archibald Macmillan, claimed to have been captured by Jacobite forces while buying cheese near Fort William. He was later spotted by a troop of the Argyllshire militia at the head of Loch Eil with weapons in-hand and was brought in, despite his promises that he was just then on his way to surrender. All three of these men had their sentences of death approved by the Earl of Albemarle, who was then commander of the British forces in Scotland, in early October 1746.16

Government officials made a point to identify known deserters from the King’s army in jail returns and lists of prisoners, ensuring they would remain tracked until proper justice could be administered. From a group of prisoners sent from Perth to Stirling on 12 May 1746, for example, ten of eighteen are designated as deserters and associated with their former regiment. In a list of six prisoners brought to Inverness tolbooth by Loudoun later that July, two of the entries are annotated with detailed information about their previous service.17 Prosecutors likewise relied upon informants and witnesses to help identify defectors and ‘mutineers’, and orders were widely circulated to aid in their discovery, upon which time they were to be sent back to their regiments for trial or punishment.18 While stationed at Edinburgh in October 1745, the mariner Robert Bowey claimed to have seen 200 prisoners ‘with the Livery of his Majesty King George’ guarded at Holyrood Abbey after Prestonpans, and he corroborated the rumour on the street that ‘they had all Inlisted with the Pretender and were in his Service’.19 While Bowey’s numbers are likely inflated, the bookseller Andrew Henderson, eyewitness to and chronicler of the rising, relates that Lieutenant- General Henry ‘Hangman’ Hawley, who commanded the British troops at Falkirk, had nineteen of these deserters either hanged or shot upon evidence from a redcoat sergeant after Edinburgh was retaken.20 Four soldiers were lured out of their Jacobite regiments by a government spy before they were tried and executed in Carlisle, and the Earl of Ancrum reported that five others who listed with the enemy were to be strung up in Aberdeen.21

Though many more surely flipped during the eight-month campaign, the names and former regiments of just over 200 British army deserters who were found to be in Jacobite service are present in government records.22 The largest number of these (31%) came from Guise’s 6th Regiment of Foot, which was one of the first units to engage with the Jacobites in the Corrieyairack Pass in mid-August 1745, followed by 8% from Loudoun’s independent Highland command.23 Henderson reported that many of these deserters were captured after Prestonpans and came to form ‘most’ of John Roy Stuart’s Edinburgh Regiment just before the march to England, but this hardly explains the distribution of former British army soldiers in many other Jacobite units throughout the rest of the campaign.24 By no means did the defections all come in one fell swoop after the first battle, but rather by dribs and drabs as the rising developed. In fact, numerous deserters from the British army had joined Scots and Irish regiments in French service before the ’45 even had began and thus stepped foot upon their home soil as enemies of the state.25

This article first appeared in the Jan/Feb 2023 issue of History Scotland (Vol. 23 No. 1)

as part of its regular Spotlight: Jacobites column.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people who were involved in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the protean nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and accessible research.