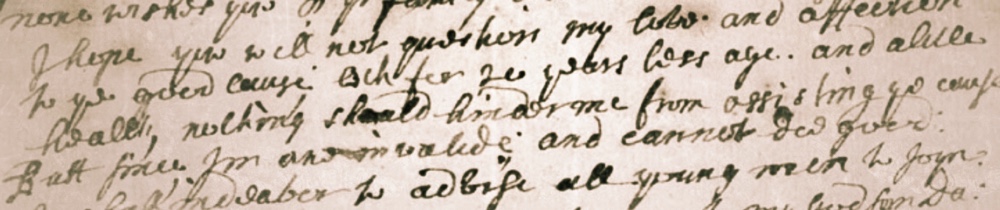

I hope yew will not question my love and affection to ye good cause. Och for 20 years less age, and a little health, nothing should hinder me from assisting ye cause. Butt since I’m ane invalide and cannot doe good, I shall indeaver to advise all young men to Joyn.

There were a number of different reasons why someone might join the Jacobite army in the late summer of 1745, just as things were starting to heat up after the arrival of Bonnie Prince Charlie in the Western Isles of Scotland. Specific motivations to pick up arms or to help others to do so were as disparate and multi-layered as the individuals involved in the conflict, as were their levels of sustained commitment as the campaign progressed.

Some fought for the ancient claim of the Stuart monarchs, and some stood in opposition to the parliamentary union that bound together England and Scotland into a single kingdom. Many resented being forced to accept the authority of the presbyteries over the traditional Divine Right of kings, especially when it came bundled with oaths of fealty to a sovereign from Lower Saxony. Others reckoned that they would be better off without the influence of a comparatively liberal representative government, an establishment which to them symbolized the decay of traditional values – especially in certain long-established and autonomous regions of ‘North Britain’.1

Those who felt disenfranchised may have fought simply to restore positivity and fortune to their county, region, or nation. Some signed up not because of any ideological attraction to ‘the Cause’, but because of a rising discontent with the state of the trades and the widespread corruption within urban guilds.2 Hundreds volunteered or were sent to Scotland in the service of Louis XV to support the Jacobite effort and to simultaneously disrupt Britain’s Continental focus in the War of the Austrian Succession. And many others were coerced to join the Jacobite ranks by recruiters who often leveraged or abused the authority of heritable jurisdictions to secure sufficient quotas of rank-and-file troops. When threats or bonds of tenancy were not enough, schemes of blackmail, destruction of property, and even physical kidnapping were sanctioned to ensure that Jacobite regiments had enough mass to threaten one of the most capable armies in Europe.3

Perhaps the most significant factor driving plebeian Jacobite support, however, was simply the influence of other people. Sometimes this manifested in the magnetism of prestigious local leaders, outspoken ideologues who exercised their charisma to inspire or manipulate, or persistent recruiters who would not take ‘no’ for an answer. Numerous instances of personal influence upon rebel participants can be seen through much of Scotland during the rising, a solemn reminder of both the grey areas and the human condition in civil war.4 Familial pressure, too, played an important role in fortifying Jacobite military and civilian networks. In many cases, this was merely a matter of relatives with similar beliefs or designs making the decision either to join up with Charles Edward Stuart or to support his troops with supplies, intelligence, or other logistical assistance.

The clan structure, heavily based upon complex webs of kinship, relied upon long-established expectations of service in times of conflict. Pressure to participate (or to refrain from doing so) amongst the fifty principal Highland clans was leveraged both by figures of prestige or familial authority and also by clan tenants, some of who drifted to Jacobitism as a protest against modernization and commercialism encouraged by their superiors.5 The majority of the clans were divided by conflicting loyalties, for as many different reasons as anywhere else in Britain. These lines of conviction did not often remain static through the entire Jacobite era, and in fact the Gàidhealtachd trended away from Jacobite sentiment as the eighteenth century unfolded and social tensions increased between clan elites and their constituents.6 Allegiance to clan chiefs and landlords was usually predicated upon contracts of tenancy and often dictated the ‘dedication’ of individuals to the cause. That authority, however, was difficult to maintain or impose once the men ventured beyond familiar boundaries, especially as the progress of the rising peaked and then dipped.7

Outwith the distinctive fusion of kinship, tenancy, and service in the Scottish Highlands, other peculiar familial interactions are also represented in archival sources. Of these, an infrequent but curious scenario is portrayed when a parent or other relative formally offers up their children for use in the Jacobite army. It was not uncommon to see fathers marching and fighting alongside their sons, but sometimes this service was offered in their steads – whether that be due to age, medical condition, or ambivalent feelings about the rising itself. James Stirling of Kier, a veteran of the 1715 rising, at sixty-six years was likely too infirm to once again join up himself. Instead he travelled to Edinburgh, where he presented his two sons directly to Charles Edward for his use in Elcho’s troop.8 Near Dunnideer in Aberdeenshire during the early days of the rising, David Tyrie penned a remarkable letter to John Gordon of Glenbucket wherein he apologized earnestly that he was far too old and sickly to join the endeavor. To support the venture, however, he instead offered the service of his grandson:

Since Im not capable my self to Doe good to him. I must recomend my Grandsun Da. Grant to yew. so he is willing to serve under your Command And his imployment is ane surgeon having served…Ross in Old Meldrum near thrtie years. And is plenety Capable of his trade. So yt I think he may be of great use to yew & yr followers.9

It appears that by making such an offer, Tyrie was also ensuring the welfare of the boy, as well as that of a second grandson and a god son, both of whom he also recommended for use in Glenbucket’s command. In exchange for serving in the army, Tyrie explicitly reminds Gordon that he expects the boys to be cared for and to be given subsistence, since they had no other means of such comforts. What lies unspoken, however, is the difficulty of life for some in the Scottish hinterlands and how riding the momentum of the Jacobite endeavor was a very real option for securing basic sustenance – if not for political or ideological principle. As it would ironically turn out, provisions, supplies, and regular pay became impossible to secure without extensive and effective logistical networks in place, and the Jacobite army eventually lost cohesion in part because of this insufficiency.10

Other captured Jacobites who were examined by government officials claimed they were instructed to fight by their parents, like the son of the laird of Northside and Peter Bell, who joined the Prince’s Lifeguards under his mother’s influence.11 Andrew Johnstone, a young man from the Canongate in Edinburgh, was enlisted in the Scots Greys before his father ‘with Threats & Menaces obliged him to quit the King’s Service’ and join the rebels instead.12 One of the youngest participants to be recorded in the Jacobite army was fourteen-year-old John Auld, a boy from Falkirk who claimed to have been forced by his stepfather to join Kilmarnock’s cavalry as a drummer.13 Like most claims of innocence by those facing charges of high treason, excuses of familial compulsion without sufficient evidence to prove them were generally not accepted by the government. Yet mercy was often shown to some of the younger boys who were either unwittingly roped into the rising or who played up their vulnerability due to being of a tender age.

Occasional cases of family pressure would spectacularly backfire after the rising was over. The Old Fox, Simon Fraser of Lovat, sent his son to raise particular septs of the Fraser men in his place so he could hedge his loyalties for as long as possible.14 In the end, of course, it still cost the elder Fraser his head. The younger Simon, meanwhile, never really wanting anything to do with Jacobitism, went on to fight for the British army in the French and Indian War, attaining the rank of Major-General and thereafter securing a seat in the House of Commons.15

Lest we forget the protective instincts of some parents, however, we may turn to the indomitable Mrs Mercer, whose son Laurence was picked up by British dragoons near Angus in June 1746. According to Lord Ancrum, who was in charge of the King’s forces encamped at Aberdeen after Culloden, this Jacobite soldier’s mother attempted to slip ten guineas into the patrol sergeant’s hand to let the boy escape. No doubt Ancrum was pleased that the sergeant refused, which he conveyed to Everard Fawkener in a report approving that the officer ‘had more honesty than to do it’.16 To Mrs Mercer, bribery was clearly a risk worth taking in order to secure the safety of her son.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and Open Access.

Thank you for a most interesting blog post. I was wondering if you had access to the recently digitised Stuart papers as part of the database.

Thanks very much for reading and for commenting, Karen. We do indeed have access to the Windsor collections online. While persons mentioned in those collections have not yet been parsed out for entry into JDB1745, the team is currently in the process of going through the documents in order to do just that.

Great work !

I hope you are aware that David Tyrie’s son, my 6xGreat Uncle, Father John Tyrie was Chaplain to Glenbucket’s Regiment throughout the 1745 campaign as far as Drumossie Moor where he was wounded. His home at Bochel just north of the College of Scalan, where he had been master in the 1720s, was burned by the Hanoverian forces. Fr John Tyrie had probably been estranged from his brother, my 5xGreat Grandfather, Rev. James Tyrie since the 1730s when James left the Roman Catholic priesthood for the Church of Scotland. James was seeking to establish himself in the Ministry in Orkney… Read more »

Hi Gary, thanks for your note. You can find the full reference for David’s letter attached to the second pull quote. It is held in the Captured Stuart Papers at Windsor Castle.

Gary

Gary, I have just stumbled across this whilst doing some research into the Tyrie’s on Dunnideer as my 6x Great Grandfather was David Tyrie (1696-1750), so we may be related in some way.