In early December 1746, well after the active threat of the last Jacobite rising had waned, the British government was still collecting intelligence regarding known rebels who had not yet been apprehended. The report of Alexander Robertson of Straloch from that month, presumably sent to the Duke of Newcastle, is especially interesting for two specific reasons. First, it explicitly calls out the forceful tactics of impressment used against unwilling tenants on David Ogilvy, 6th Lord Arlie’s estate. Second, within it Straloch proposes an elaborate plan to trick lurking Jacobites into revealing themselves – a plan that is both impressively calculated and devious.1

Known informally as Baron Reid, Alexander Robertson of Straloch was a gentleman from the Strathardle area of Perthshire whose family had long been aligned with the house of Argyll and the Hanoverian government. He was a vassal of James Murray, the loyalist Duke of Atholl, and he spent much of the rising assisting the government by providing intelligence reports and offering counsel regarding methods to suppress the rebels.2 Straloch was evidently quite well connected during the Forty-five, corresponding directly with Newcastle – the secretary of George II – and Duncan Forbes of Culloden, the Lord President of the Court of Session. To these officials he sent a series of bulletins between 1745 and 1747 leveraged from the network of Presbyterian ministers in Perthshire and the north-east who received and conveyed useful intelligence about Jacobite movements.3 Straloch was effective enough as an informant to warrant a mandate for capture from Atholl’s brother William, the Marquess of Tullibardine and titular Jacobite Duke of Atholl.4

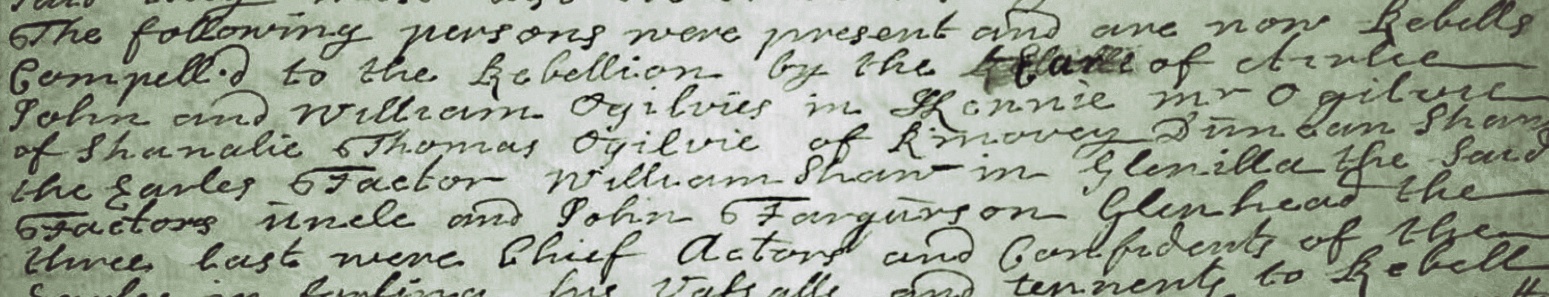

The report from early December records the results of an investigation about the reluctance of Airlie’s tenants in Angus to join the Jacobite army – a rather surprising conclusion given the size and effectiveness of Lord Ogilvy’s regiment throughout the campaign. Straloch describes that a meeting took place at Cortachy at the behest of the sitting Earl of Airlie, David Ogilvy’s father. Over a dram, the elder Airlie told a number of his factors and vassals that they simply had no choice but to take the field with his son ‘or be destroyed’. The following men are identified as being present at the meeting:

- John and William Ogilvies in Kennie

- Mr [David] Ogilvie of Shanalie

- Thomas Ogilvie of Kinovey

- Duncan Shaw the Earles Factor

- William Shaw in Glenilla the said Factors uncle

- John Fargurson Glenhead 5

Both Shaws and John Ferguson, Straloch recounts to Newcastle, were absolutely instrumental in ‘forsing his Vassalls and tennents to Rebell’, and that all of the above were living ‘pretty openly’ on the estate and should therefore be captured before they were able to escape:

All the Earles Ground Officers were Imployed and had orders from him to distress and forse all his tennents to take arms or pay money to Levie men for the pretender great care must be taken to apprehend them…

These men would make especially good witnesses for charges of treason against captured Jacobites, as they were the prime recruiters on the Airlie estate and would undoubtedly have firsthand knowledge of many others who were involved with the rebel army.

He goes on to recommend an informant by the name of Alexander Crook, who served briefly in the Jacobite army as a surgeon but was thereafter allowed to continue his medical practice in Coupar Angus caring for the sick and injured soldiers of the British army. Crook was described as ‘a very fitt person’ who evidently had much to prove in order to return to the government’s good graces. As his son was hoping to follow in his footsteps and build a business one day, Crook’s eagerness to assist was apparently a foregone conclusion.6 Once Crook had pointed out the men complicit in Jacobite recruiting, Straloch cautioned stealth in arresting them so as not to scare their quarry into the hills of Braemar, where the Airlie men might be able to make an escape: ‘the Rebells must be first aprehended before they be Spake to least the Secrett be Blown’.7 To counter this possibility, Straloch suggested a devious ploy involving the infiltration of Gàidhlig-speaking agents amongst their targets:

…by planting Some trusty Highland Souldiers there who must put on Tartan Cloaths and not their Regimentals and pretend they are Rebells Lurking thre till they find their Oportunity.8

The details of this scheme are repeated in an attached letter within the report made out to the Rev Charles Bog, a Presbyterian minister in Braemar who was named as a witness to ‘the open forse that was put on the Earles tennents’.9 Bog was considered to be another reliable informant who was actively willing to help apprehend known Jacobites, and he was not alone in that station. The extensive network of parish ministers serving the Church of Scotland was one of the British government’s most effective tools in obtaining intelligence about rebel activity, and in addition to Bog, Straloch mentions a number of them who also knew of the Airlie impressments, including:

- Mr [Alexander] Scott, minister at Kingoldrum

- Mr [John] Robertson, minister at Alyth

- Mr [George] Ogilvy, minister at Kirriemuir

- Mr [Laurence] Brown, minister at Lintrathen

- Mr [Robert] Robertson, minister at Kirkmichael

- his son Mr [William] Brown, minister at Cortachy 10

This network of clergy was only part of Straloch’s full lattice of intelligence, however, and he helpfully names a number of other agents in the country whom he believes would assist with the plan. Some of these men were captured Jacobites, like Major James Stewart, who was a factor to the Duke of Perth, and Henry Ker of Graden, who served as an aide-de-camp to Lord George Murray. Others had professional relationships with the earls of Airlie, and though they were never in open rebellion, they nonetheless served as advisors and likely held sufficiently incriminating evidence against their employer. These included John Smith of Balhelvie, who functioned as Airlie’s Bailie of Regality, and James Smith, WS, the earl’s attorney in Edinburgh.

With this broad net of operatives and witnesses, Straloch enthusiastically lobbied to put his plan into action as soon as possible. He had the pieces in place to make it happen and he was just the man to see it through:

…if youle appoint an honest Englishman of Sence who will meet with me frequentlly I think I may be usefull in this and many other affairs of some consequence but if the Secrett be not well keept it will lose the Influence I have among the Highland Clans which may be of more use to his Sacred Majestie I have always thouht that the Kings friends in Scotland should be Cherished and his Enemies Restrain’d not Exasperate that Jacobitisme itself and not Jacobits ought to be Chieffly Struck at.

Straloch reminded Newcastle that he had risked his life to obtain this information, but it is not clear if the operation was ever put into effect. Duncan Shaw of Cortachy, Airlie’s primary factor and Straloch’s main target, escaped after Culloden with at least five of his uncles and stayed out of sight until well after the violence had subsided. Shaw and his family can be traced to at least 1768 with no apparent harassment or capture on their records.11 Thomas Ogilvie of Eastmills (‘of Kinovey’ above) was captured on 27 April 1749 and died at Edinburgh Castle in 1751 when he tried to escape, falling upon the rocks of Castlehill.12 What became of the other men on Straloch’s list is not currently known, but it is presumed that none of them were ever apprehended.

Alexander Robertson of Straloch continued to advise the British government through the spring of 1747, whereupon he penned a series of extravagant memorials that advocated the establishment of fortification lines and parties of occupation to quell thievery and further Jacobite activity in the Scottish Highlands.13 He also contributed to securing the stay of execution and eventual release of Jacobite officer Francis Farquharson of Monaltrie, for whom he penned an inspired memorial addressed directly to the Duke of Cumberland.14 By the outbreak of the American Revolution, Straloch was in dire financial straits and was forced to sell his estate in Strathardle, explicitly blaming his ruin upon his loyalty to the house of Argyll. His principal creditor in Edinburgh, Duncan McDonald, was so thoroughly fed up with the Baron’s penury that he wrote to him, ‘I never met with anything that gave me more vexation than my acquaintance with you and I hope never shall. Your conduct I can never forgive’.15

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and Open Access.

What a fascinating story – yet another one of the intriguing characters to have emerged from Atholl. I’d come across ‘Baron Reid’ a number of times in my research without – I have to confess – quite understanding his role as spy.This info will be very helpful. On another tack your comments about Ogilivy’s men chimes with my confusion about how people who were coerced into the Jacobite army then went on to achieve so much. Hope you will be able to shed more light on this apparent paradox at some point.

Thanks very much for your comment, Mark; I’m glad that this account of Robertson might be helpful in framing your own work. Your interest in the impressment paradox is certainly understandable and I have every faith that we’ll dig up many more examples in the near future.

[…] drawn up by Scotsmen – Highlanders, in fact – who remained loyal to the established Whig order. Alexander Robertson of Straloch, the dutiful spy from Atholl known as Baron Reid, submitted two memorials to the Duke of […]

Most interesting account and relevant to my Brodie/Shaw ancestry, but I am puzzled by one statement which I believe to be in error, namely this: “Duncan Shaw of Crathienard, Airlie’s prime factor and Straloch’s main target, escaped after Culloden …”. I believe that in fact Duncan Shaw of Crathienard died in 1726 and it was his grandson, Duncan Shaw in Cortachy Factor to Airlie (and son of James Shaw of Daldownie) who was involved at Culloden and escaped afterwards. The five sons referred to are, I believe, correctly described as Crathienard’s sons. I would appreciate if Darren or someone more… Read more »

Hi John, thanks very much for your comment here. You are correct that the Duncan Shaw referred to in the vignette above lived in Cortachy or Kirriemuir and was the son of James Shaw of Craithienard and Daldownie. I had given him the title of his father’s estate in this piece for purposes of identification, though I am aware that Craithienard was sold sometime before Duncan the elder’s death. (I have also seen references to a farm called Crandart in Glenisla which was connected to the Shaw family before 1726 – Mackintosh mentions this in the Forfarshire muster roll and… Read more »

Hi Darren

Thankyou for your quick and helpful response. I’m very glad to have input from those more knowledgeable regarding my rebellious Shaw ancestors. Darren, do you or any of your website followers, by any chance know who was the wife of Duncan Shaw(in Cortachie) I have been searching for this information for a long time without success.

I do have lots of information on Duncan Shaw’s 4 children including David Shaw (my ancestor) who made his fortune in Jamaica, in case there is any interest.

Hi John, I am certainly no expert in genealogy, so it might take some resources more closely connected with family history to track down Duncan’s wife. Mackintosh notes that she was the daughter of William Brown, a writer/advocate in Forfar who also served as bailie and provost after the rising. As Brown was Robert Wedderburn of Pearsie’s agent, you might wish to contact the Dundee City Archives, which currently hold the Wedderburn of Pearsie Papers. I’ve had a look through them myself, but they are quite extensive. At the very least you have a line on her maiden name!

Thankyou Darren. That is of immense help to me. I had a previously made a note about the daughter of William Brown, just as you describe it, but had lost the reference. The old parish records shed no light on the marriage and children as the registers are missing for the critical period. I was unaware that Brown was Robert Wedderburn of Pearsie’s agent so I will be chasing down that lead. Just finished Robertson’s wonderful book “Joseph Knight” so I now know a little about the Wedderburns, and have been intrigued by the parallels with the Shaws who were… Read more »

Yes, indeed: that’s the correct source. Some notes about Duncan are in the biographical sketches on pp. 155-6. Thanks very much for reading along and for your engagement here, John. Feel free to contact me via email (darren at jdb1745 dot net) with any further questions or thoughts, too.

My theory about the missing baptism and marriage registers during this period is that they were deliberately “lost” or destroyed to hinder the process of identifying and tracking down those associated with the rebellion. Either that or they were confiscated by the Royalist forces to aid them in their search for culprits.

That’s certainly possible, but consulting baptism and marriage records was generally not how rebels were identified by the government. The three most significant processes were empirical evidence, suspicion of conduct, and the absence of attestation by the ministers of the Church of Scotland.