To-do lists are not only productivity tools for busy modern lives. They were also used extensively by eighteenth-century British government officials to keep pressing topics close in mind, and some even fashioned their memoranda as checklists to ensure they did not miss anything especially important. We see this practice in a document from the British National archives, where Sir John Sharpe, Solicitor to the Treasury during the Jacobite prosecutions after the Forty-five, lists a number of tasks to complete in the winter of 1746-7.1 It is a particularly interesting archival document because it gives us some idea of what critical topics of conversation concerning the prosecution of Jacobites kept government officials occupied. The fact that this task list was written nine months after the Battle of Culloden demonstrates just how much judicial red tape still existed well after the last rising itself had burned out.

Paraphrasing Sharpe’s list of to-dos, we may look in on numerous important points of policy as well as how Jacobite prisoners under charges of treason were processed and treated:

Item #1

Considering the method of how to send prisoners-of-war in French service back to France.

Sharpe notes that he needed to speak at length with Sir Everard Fawkener, the Duke of Cumberland’s secretary, about a peculiar issue: just how to discern which of the prisoners-of-war were really from France, and which were actually born within the Three Kingdoms. This was an important distinction because both the rights and the treatment of prisoners facing charges of treason were different depending on whether they were ‘subjects of the crown’ or legitimate foreigners under the protection of Louis XV. Perhaps unsurprisingly, more than a few of the captured Scottish and Irish soldiers in French service feigned foreign provenance in hopes that it might secure them a lighter sentence – or even freedom altogether. After the recapture of Carlisle by the British army, for example, a Jacobite adjutant in Lord Kilmarnock’s cavalry troop masqueraded as a French officer until a corporal from Hamilton’s Dragoons revealed him to be an Irishman with whom he had already been familiar.2 The Lord Justice Clerk Andrew Fletcher, however, saw no difference between those born in Britain or beyond, stating that anyone should be answerable to charges of high treason if they ever ‘had Residence in the King’s Dominions before the Rebellion’.3

Item #2

Settling the bail and surety bonds for Archibald Stewart, the provost of Edinburgh during the Jacobite occupation.

The complex and meandering case of Provost Stewart took up a considerable amount of the government’s focus, all of which was thought fully justified considering the charges against him. The Jacobite entry into Edinburgh on 17 September 1745 was so quick and unopposed that British ministers were convinced Stewart was complicit in the act, and they wanted him punished accordingly.4

…from the Evidence contained in the said Papers there is Sufficient Ground to proceed against the said late Provost for a High misdemeanor, in having many Ways Acted Contrary to his Duty and thereby Suffered the City of Edinburgh with the Cannon, Arms Ammunitions and Provisions to fall into the hands of the Rebels, For which Offence he must be Prosecuted before the Court of Justiciary in Scotland…5

The terms of Stewart’s bail settlement needed to be discussed with Dudley Ryder (Attorney General) and William Murray (Solicitor General) and Sharpe made it a point to follow up with them, as evidenced by this item in his list. In the end, a recognizance was set at £5000 to ensure the harried former provost’s appearance at the first day of his hearing on 20 March 1747 at the Justiciary Court of Edinburgh.6

Item #3

Direct the Lord Advocate of Scotland to commence a prosecution against Provost Stuart according to the terms set by the Attorney and Solicitor Generals.

Lord Advocate Robert Craigie was ultimately in charge of the Jacobite prosecutions in Scotland after the Forty-five, and he had quite a load of work to tackle in the years after Culloden. Though Archibald Stewart was first taken into custody in December of 1745, he was not released on bail until 23 January 1747, three days after Sharpe’s memorandum was finalized.7 The trial would plod through the summer and late into the autumn of that year, drawing much attention from the public. On 31 October, the Lords Commissioners of Justiciary found Archibald Stewart not guilty of neglecting his duties and he was duly acquitted.8

Item #4

Ensure that all common men who have petitioned for transportation be immediately transported and thereupon immediately pardoned.

The prosecution of Jacobite prisoners contained many facets, with varying sentences handed down that were based upon different types of evidence. Even the prisoners themselves were sorted into categories, both by degrees of guilt and acts of rebellion, as well as by social and economic standing. The official judicial process was quite efficient and based on clear protocol, but the penal apparatus, including jails and courts in both England and Scotland, was hugely overtaxed by the influx of prisoners from late-1745 on. Though the British government is vilified today for its treatment of Jacobite captives, the vast majority were released or pardoned without further punishment. Executions were sparse and were generally reserved for the most notorious or active agents in the Jacobite fold. It was still important for King George II to appear merciful to his subjects and to the rest of the world, even while stamping out Jacobitism once and for all. This was the government’s official position and it was publicly demonstrated by the due process of prosecution. The real bloodbath, of course, began with the British army’s brutal suppression of recalcitrant communities throughout Scotland, mostly but certainly not exclusively in the Western Highlands.9

The majority of the plebeians caught up in the rising were given numerous chances to turn in their arms and simply return home. For those who continued on and who were subsequently captured with enough evidence against them to warrant their incarceration or prove their guilt, the government could really only justify one of two sentences: acquittal or banishment. Barring mass executions (which was never going to happen), removing from the kingdom those subjects who were seen as traitors was the best way to prevent yet another Jacobite rising from bubbling up in the future. While enforced forfeiture stripped landed peers from their titles and ancestral estates, transportation was by far the most common sentence for the common Jacobite.10

Petitioning for transportation was in some measure an admission of guilt, but for many it was no more than an acquiescence to a foregone conclusion. Yet even the option of doing so was considered a privilege that the landed classes were debarred from receiving.11 Those plebeians without bulletproof alibis were organized into groups of twenty for lotting, with one unlucky person from each group selected for trial or further examination. The rest were to be transported to British colonies, usually in the New World, where they would either serve out terms of indenture or life-long sentences of hard labor. Ironically, this was referred to by government officials as ‘mercy’, while going to trial was categorized as ‘justice’.12

For the British government, this representative method of removing an estimated 3500 bodies thronging the penal system was the only efficient way to get through all of the cases. As Sharpe notes in his memorandum, the upshot of being transported was that it carried with it a full pardon from all charges of high treason. For this reason, some prisoners who knew the extent of their guilt actively chose to petition for banishment, perhaps taking their chances in hopes of escape or one day returning home. They, of course, would not have known that virtually all of those who were lotted for trial would have their sentences commuted from death to transportation or eventual release.13 This fact leads us directly into the final item on Sharpe’s task list:

Item #5

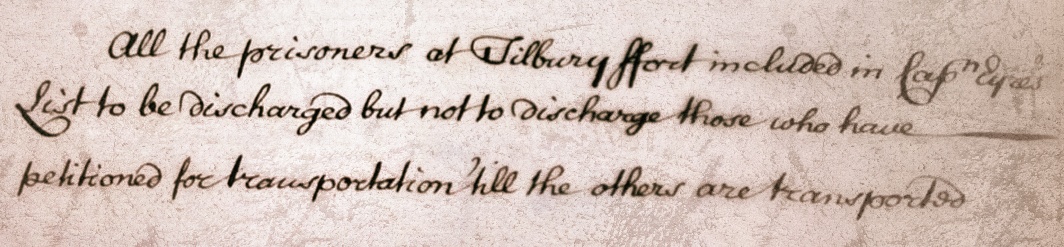

All of the prisoners held at Tilbury Fort are to be discharged, but not to discharge those ‘who have petitioned for transportation ‘till the others are transported’.

This is certainly the most intriguing entry of the lot, and it begs some questions about the transparency and character of the government officials overseeing the Jacobite prosecutions. Taken at face value, it might simply be a reminder about the order of process involved with numerous waves of prisoners from different jails that were to be readied for transportation to the New World colonies. Analyzing the phrasing more closely, however, it could be interpreted as a cunning method to deceive prisoners into volunteering themselves for removal from the kingdom.

After the 1715 rising, the administration of George I faced great difficulty in getting captured Jacobites to voluntarily petition for transportation. At that time, it was illegal for the state to forcibly order indenture upon convicts who had not agreed to sign on themselves. This was enough of a problem that an Act of Parliament was passed in 1718 to allow a sentence of transportation to be conferred without assent and to be enforced at the judge’s will, which undeniably changed the landscape of prosecution against Jacobite prisoners after 1745.14 Indentures were partially established to fund both criminal and emigre transportations, which then further benefitted the state by adding an entire expatriate class to the inadequate labor force in the colonies.15

It therefore makes sense that the government would want to encourage as many prisoners as possible to voluntarily petition for transport upon indenture, as there was simply no way to arraign and convict the thousands of miserable captives held in steadily worsening conditions amidst the many English jails and prison hulks. Besides the fact that the majority of cases were not prosecutable due to lack of evidence, it would remain prudent for the state to nourish the fledgeling business of transporting criminals to the New World plantations – and business would be good for the next thirty years. There is evidence in 1716 of this ‘encouragement’ amounting to verbal abuse and the physical bullying of prisoners who had refused to sign their indentures, and other memoranda containing procedural precedents for transportations convey that emotional coercion was part of the policy.16

Signifying his Majesty’s Displeasure at the Rebells not Embracing those Conditions of Mercy he had graciously allowed and directing that if the same Spirit of Obstinancy Continued and that they wou’d not submitt to the Terms of Mercy and voluntarily ask it of his Majesty in that Case to proceed to some further Degree of Justice and try some of those on whome the Lotts had not fallen agt whom there was sufficient Evidence to Convict them.17

Plainly stating that George I was not interested in carrying out mass trials after the 1715 rising, one government official noted that it was not the king’s intention ‘to go any farther than to strike a Terror’ and that it would be necessary to ‘keep them under such sort of Tie that they may not appear as it were in defiance of the Government or think themselves secure as if they had done nothing to deserve Punishment’.18 It is reasonable to interpret John Sharpe’s note through the same lens in 1747. We may surmise that until the initial shiploads of 355 prisoners at Tilbury Fort and upon the Thames hulks who signed petitions for transportation actually embarked for the colonies, Sharpe wanted both them and the remaining inmates to be kept in the dark about each other’s fates. This especially if the later groups were only to be set free upon successfully controverting suspicion or providing evidence against others, like so many indeed were.19

We know that in fact many hundreds of prisoners were released or discharged without transportation or trial, either upon bail, recruitment into the British military, or on general pardon under the 1747 Act of Grace. Perhaps the number of souls had been so great that the cost or paperwork involved in establishing transport contracts with willing merchants became economically or logistically obstructive.20 Sharpe, Ryder, and Murray met with the Duke of Newcastle on 13 February 1747 to discuss what to do with the prisoners at Tilbury who were held back, and the minutes of their conference explicitly refer to the discharge of those with strong – but not sufficient – evidence against them.21 Sharpe’s reminder to delay the discharge of prisoners until others under the same petition had departed is a questionable one, and it may be interpreted in more than one way – none of them any help to those who had already set sail for the plantations.

According to Captain Stratford Eyre’s detailed roster of prisoners held at Tilbury and on the prison hulks, not including those who had been lotted for trial, an additional seventy-five persons were held back for further examination or to be used as witnesses against other indicted rebels.22 Presumably, a number of those who remained were later also convinced to sign the petition. Eyre’s roster was submitted in mid-October 1746, Sharpe’s to-do list was written on 20 January 1747, the solicitors’ meeting took place on 13 February 1747, and transport ships left London in waves from early March 1747 to the first quarter of 1749.23 To get a certain picture of what Sharpe was proposing, it would be necessary to trace the fortunes of those who were not immediately transported to measure whether they were indeed discharged and what that designation actually meant in each case. As more archival evidence is brought together from disparate sources on both sides of the world, studies like this will certainly be possible.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata organization, and Open Access.