After a handful of Donald Cameron of Lochiel’s men slipped through Edinburgh’s grand, turreted Netherbow Port virtually unopposed, the capital of Scotland, excepting its imposing castle, was firmly in Jacobite control for most of the late summer and autumn of 1745. From 17 September to 31 October, high-ranking soldiers and officials under the leadership of Charles Edward Stuart consolidated their provisional government in ‘North Britain’ at Holyrood House, and in the fields around Duddingston Village they bolstered both the numbers and training of the men who formed the military arm of the Jacobite cause. This distinctly irregular army was essentially the crowbar with which Charles Edward would attempt to pry George II off the thrones of the Three Kingdoms while advocating for his father, James Francis Edward, who was proclaimed at the mercat cross as James VIII of Scotland on the very same day the burgh was taken. Cobbled together in fits and starts before the capture of Edinburgh, it was never a sure thing that enough support would materialise or that the enthusiasm it bore would translate to success on the battlefield when open conflict eventually came.1

The lightning-quick and overwhelming Jacobite victory at Prestonpans in the early morning of 21 September boosted the confidence not only of Charles Edward’s Council of War but also that of many of the common soldiers across the ranks. Now that this army had faced seemingly the best that the British government had to offer, the zeitgeist of the mission was astir and word quickly spread to the surrounding localities that this revolution, long-desired and attempted on numerous occasions before, might really happen this time. Recruiting drives marshalled in places like Perthshire and the north-eastern counties, like Aberdeenshire and Forfarshire, eventually secured valuable additions to the nucleus of Highland Jacobite troops in Edinburgh, with numbers swelling from around 2500 to nearly 6000 men through the month of October.2

Elites of significant esteem arrived at Holyrood with tenants, servants, and other adherents in tow, prepared to gamble their estates and their lives in favour of the promise of a Stuart restoration. Renowned Jacobite personalities like Lord Ogilvy, John Gordon of Glenbucket, and Alexander Forbes of Pitsligo entered Edinburgh in the first week of October with as many as 1400 men between them, demonstrating the popularity of Jacobite aims in the markedly Episcopalian north-east. These troops joined with the others and were fashioned into proper regiments, and they were subsequently drilled as regular soldiers upon Edinburgh parklands like Duddingston and Leith Links. Jacobite officers requisitioned supplies from the capital’s merchants and by 20 October the army had commissioned over 5000 pairs of shoes from the workshop of a single cordwainer, Walter Orrock, who was politically sympathetic to the cause.3

Yet even during this early stage of the rising when soldiers were joining the army in large numbers, at its apex of optimism and morale, Jacobite officers were faced with the nagging problem of desertion and how to discipline the men in order to prevent it. Though alternately exaggerated and marginalised in the historiography of the event, the damage done to martial cohesion by both intermittent and large-scale desertion within the Jacobite army was something that comes up repeatedly in archival documents from both sides of the conflict, including intelligence reports, court depositions, and regimental orderly books.4 The most common periods for significant desertion through the campaign were those immediately following a battle; one account of a military review undertaken a few days after Prestonpans claims that as many as 1000 men had gone absent from the camp.5 It is no wonder why soldiers sometimes returned home after facing injury and death in pitched battle, though we must also consider the terms stipulated in contracts of military service that were common amongst tenants in Scotland, some of which took into account the agrarian maintenance of planting and harvest. Other recruits who were forcefully conscripted into the Jacobite army, or who felt that the terms of their contracts of servitude had been broken or violated, might have considered themselves justified in picking up and leaving, especially just after putting their lives on the line.6

During the Jacobite occupation of Edinburgh, we see some direct evidence of consequential desertion in James Drummond’s company, a unit that served through the opening months of the rising within the Duke of Perth’s regiment. Tallied at the end of September just nine days after Prestonpans, its muster roll lists ten soldiers who had left the camp without permission, including two who appear to have had taken it upon themselves to join another regiment, presumably to seek better conditions or serve more closely with friends or relations. These ten men are distinguished from another twelve who were absent on furlough, a practice that is now sometimes erroneously conflated with desertion but that was clearly distinct to the regimental command in the moment. The presence of furloughs suggests the tolerance of some Jacobite officers in allowing their men to come and go as required, though Drummond himself complained to Colonel John O’Sullivan that he was forced to let his dozen return home and had struggled to come up with the money to pay them before they left.7 These deserters and furloughs together amounted to fully a third of the enlisted men in Drummond’s company.

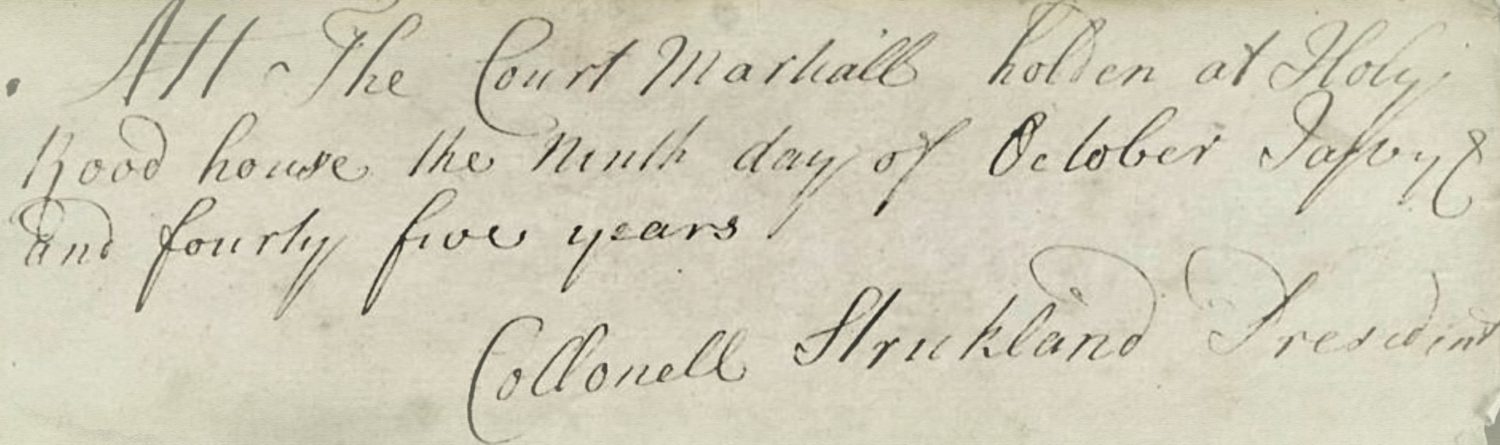

A little over a week later on 9 October, a court martial was carried out at Holyrood to punish seven men who had deserted from Cameron of Lochiel’s regiment – those among the first to enter the burgh. Named and condemned by six regimental officers and Colonel Francis Strickland, the deserters, who had been turned in by two of Lochiel’s ensigns and captured about four miles from the capital, were set to be publicly executed in front of the army by firing squad on the following day. In a demonstration of considerable restraint and clemency, however, Charles Edward reprieved all seven men on account of having ‘behav’d themselves well’ at the Battle of Prestonpans. The condition of their release was that they renew their oaths to Jacobite service and never ‘fall again into ye like Heinous Crimes for which there will be no further Hopes of Pardon’.8

While the army was in Edinburgh, Charles Edward did indeed order and carry out the executions of two men from Lord Ogilvy’s Forfarshire regiment, Robert Monro and Daniel Smith, but these were allegedly reprisals for theft rather than punishment for desertion. After all, citizens in the capital were highly sensitive to the behaviour of an occupying army that ultimately needed to rouse the ‘hearts and minds’ of the general populace to be successful.9 The paper trail indicates that Charles faced a difficult choice with regard to capitally punishing his men. While the need to maintain discipline and operational cohesion would have been of paramount importance in a revolutionary army consisting of mostly non-professional troops, reducing even a small number of its much-needed manpower was itself a threat to the needs of the campaign. This perhaps explains more compellingly why little evidence remains of exemplary executions being carried out within the Jacobite army than the suggestion of unimpeachable discipline across its ranks.10 Though at least some desertions were excused by pardon in the early days of the last Jacobite rising, looting was apparently a transgression that the Jacobite commanders were unwilling to forgive.

This article first appeared in the January/February issue of History Scotland (Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 6-7)

as part of its Spotlight: Jacobites column.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people who were involved in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the protean nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and accessible research.