Deceptions and mistruths in eighteenth century judicial cases are rarely different from those in the modern day. The indicted have always lied to save their own skins or to provide cover for people and institutions they wish to protect. Though overloaded with prisoners and casework by the end of the last Jacobite rising, the British justice system was fundamentally sound enough to make the necessary adjustments to expedite an effective method of processing that massive influx of suspected persons. Many of those lessons were learned in the aftermath of the Fifteen, wherein the first Georgian administration sought to balance victory and clemency, hoping to establish an indelible hallmark upon the nascent regime.1 Thirty years later, the system was much the same, and though the categories of punishment scaled with an increased number of prisoners taken from a significantly smaller number of total participants, a fair and accurate penal process was again pursued by many of the Hanoverian ministers who were in charge of prosecution.2

A handful of high-profile Jacobite trials have since been published, offering readers a glimpse into the legal mechanics of treason cases against the Crown, but these are especially focused on prominent characters who were singled out to be made examples of.3 The best way to learn more about the regular folks who were involved in the last Jacobite rising is to go through the plethora of original documents housed in archives across Scotland and England, and sometimes further afield. The paper trails of these individuals are often fragmented on account of them facing examinations in the different places they were held, and subsequent prison transfers and other movements can sometimes make tracking them quite difficult. Nonetheless, the raw information left behind by the accused and by the witnesses in favor of or against them can shed valuable light on both the large and small events of 1745-6. It is worth the time spent piecing together these archive-driven stories, which is a focal objective of the JDB project.

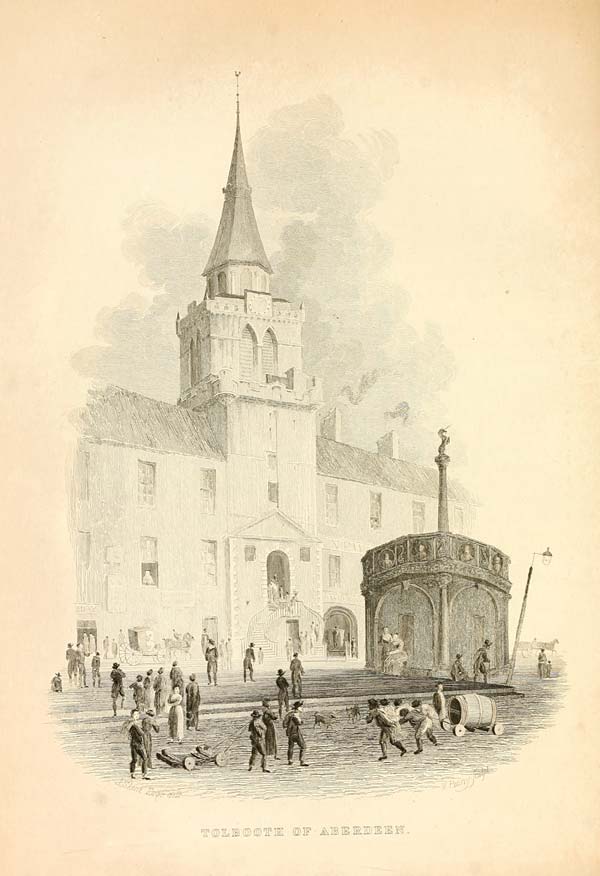

The large number of examinations of captured and suspected Jacobites near Aberdeen in the aftermath of Culloden is telling. Hundreds of rebel soldiers left the field with the remnants of the army or otherwise melted off alone into the hills, weighing the consequences of continuing on or finding a way to get home safely. The north-east of Scotland had always been a hotbed of Jacobite and non-juring Episcopalian activity, so it makes sense that so many would be picked up near the largest burgh in the region. Indeed, after Aberdeen was retaken by Cumberland’s troops in February 1746 and the loyalist council was restored to power, well-affected citizens were tasked with patrolling the town in search of hidden Jacobite refugees. Aberdeen’s guards picked up at least thirty-four people between 14 April and 17 May, all of whom were assigned to the tolbooth by the keeper, William Murdoch. By the end of July, the gaol held ninety-six prisoners for treasonable practices alone, a quota of pride boasted by the magistrates to Cumberland himself.4

…there is no place where greater care would be Taken to prevent the Escape of Rebels than here; or where more alartness has been shewen in searching for & Seizing them as the number apprehended by the Town’s Volunteers and now in Goal can Testify.5

The examinations of these prisoners and the statements made by their corresponding witnesses were recorded by the governors of Aberdeen from April to June in the attempt to provide suitable information for their handling and, if found answerable to further prosecution, for their forthcoming trials. With their lives presumably on the line, many of these prisoners nonetheless confessed to their involvement with the Jacobite army and their presence at the Battle of Culloden. Some claimed they were forced to join by influential gentry or desperate family members, and others admitted they had marched with the army but were simply there to tend to the horses and baggage of their masters, never having fired a shot. Citizens who were absent from town for any length of time were apprehended and questioned about their whereabouts, and they were called upon to provide detailed stories of their travels and responsibilities, whether personal or business-related.6 And, of course, a few of the Aberdeen prisoners offered up implausible excuses as a means to escape punishment.

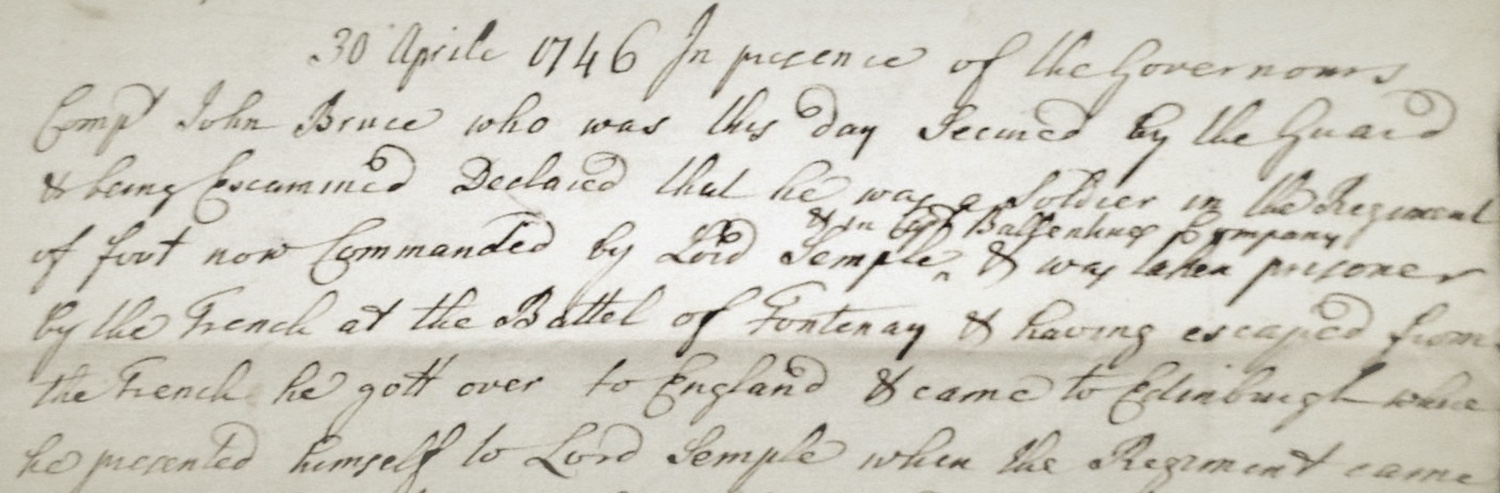

John Bruce was detained by the Aberdeen town guard on 30 April, and on the same day he recounted to the governors the complex tale of how he had arrived there. Claiming he was a British soldier from the 25th Regiment of Foot under the command of Hugh Sempill, Bruce explained that he was taken prisoner by the French at the Battle of Fontenoy on 11 May 1745, where he fought for King George. He somehow was able to escape captivity and make his way back to Britain, journeying to Edinburgh in January and seeking to meet up with Sempill so he could retake his place in the ranks. His commander would not take him back, however, which caused him to wander about the country as a peddler, until which time he was captured by the Jacobite army at Elgin in the beginning of April. Showing a knack for dramatic timing, Bruce then claimed to have been released by Charles Gordon of Blelack in Nairn just two days before the engagement at Culloden, and he swore that he was in Inverness during the battle itself, having absolutely nothing to do with the rising all along.7

Even if this remarkable alibi did not appear to have some fatal holes in it, ensuing statements by two pertinent witnesses would render it flaccid. One of these men, John Ross, worked as a mason in Aberdeen and he refuted Bruce’s story, telling the officials their prisoner had boasted to him of an entirely different adventure: that he had been on the march with the Jacobite army in England and was taken prisoner by the King’s troops in Carlisle. As Bruce was being taken to London in irons by the British army, he was able to break away and subsequently traveled nearly 300 miles to Elgin so he could rejoin the rebels. Upon arriving, however, Gordon of Blelack took him prisoner for a short time before releasing him in arms to fend for himself.

A merchant’s apprentice in town named William Forbes further told the officials that John Bruce came into his master’s shop the day before in search of ribbon to make a black cockade: the symbol of the House of Hanover. Bruce had told them of the carnage at Culloden, where he claimed to have served as an assistant to an officer in Lord Sempill’s regiment, and that his superior had run away during the fight. Forbes went on to depone that Bruce had also reported the slaughter of 1500 British troops sent after the feeling Jacobites at Fort Augustus, and that ‘the Rebels were yet in Body Seven thousand Strong’ after Culloden – a decidedly creative yarn on both counts.8

These short testimonies present us with three different variations of John Bruce’s story and how he came to be captured by the guard in Aberdeen. Collectively, they form one of the more blatant examples of obvious dishonesty within the Jacobite depositions, and the conflicting statements made it clear to the government officials that Bruce was attempting to hide the truth of his involvement in the rising. Accordingly, they ordered him to remain imprisoned in the Aberdeen tolbooth until given further orders. Three days later, he submitted a wretched petition to his captors begging for food, stating that he ‘doe make Bold to Let your Lord Ships and Govrners know that I heave nothing to Live upon hoping you will order me the Lik as a nothers heave’.9

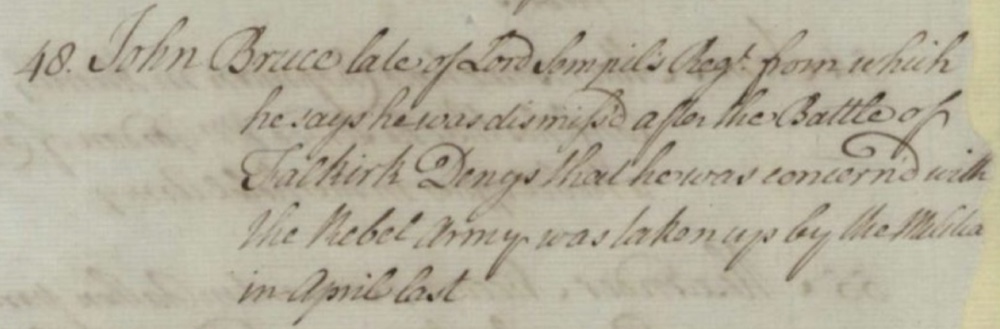

What became of Bruce in the following months is tricky to follow. The Prisoners of the ’45 notes that he turned king’s evidence by providing information against other Jacobite prisoners, and that he was later discharged. It appears, however, that the compilers have confused this man with another John Bruce, a butcher from Brechin who was also active with the Jacobites.10 By November 1746, the Aberdeen jail returns still show our man occupying his cell in the tolbooth, and this is confirmed by Crown solicitor Alexander Home on 22 November, who indicates that he was still holding on to his old alibi but with a new twist: he was actually ‘dismiss’d after the Battle of Falkirk’ by Lord Sempill in mid-January.11 Clearly not believing his story, the governors of Aberdeen curiously still referred to Bruce as a ‘deserter’ in his corresponding jail records and purposefully held him back from being taken to trial in England with the majority of other prisoners then in the tolbooth, ostensibly so he could be turned over to his former commanding officer for justice.12 Two other deserters from Sempill’s, in contrast, were handed back to the regiment’s Captain Lucas by General Humphrey Bland in Stirling on 21 August.13

What makes this case all the more strange is that in August 1746, Sempill was appointed to oversee the district of Aberdeen, being tasked with repairing the testy relationship between the restored civil authorities and the occupying military cantonment. If Bruce really wanted to petition the colonel of his ‘old regiment’, therefore, he certainly had the chance. Sempill was in residence from 12 August until his death in Aberdeen on 25 November, and Bruce was incarcerated there during that entire stretch of time.14 From the evidence that has been presented, then, it sounds like Bruce had simply concocted a cover story that involved the name-dropping of a prominent British officer whom he knew to be operating in the region. As the statement of William Forbes recalls, he even went so far as to try to craft a black cockade as part of the ruse, perhaps to ‘prove’ his loyalty and allegiance in the event of his capture. That plan obviously failed.

Can we believe everything that is stated for the record in archival documents? John Bruce’s case proves that we should not, and that fake news has always been a struggle in historical study. Much like the government officials who collected all of this disparate information and ultimately decided the fate of thousands of convicts, it helps to consider these recorded statements and depositions with a critical eye and to seek to understand the context of the time, as well as the particular circumstances of the individual. Though they could not have gotten every case right, this particular one appears to carry a compelling lineage of supporting evidence that we can corroborate nearly 275 years later. While it is tempting to have sympathy for the plight of the condemned and to take their pleas at face value, careful research with the benefit of hindsight can reveal some fascinating schemes that were attempted in the wake of the last Jacobite rising.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people who were involved in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and accessible research.

Having recently discovered (with your help, Darren) that my G5 grandfather, James Warden of Alyth, was tried on several charges of treason but released in 1746 due to ‘lack of evidence’, this article is so interesting. It would be good to know just what were the charges and why he was acquitted.

James had a twin brother, Hugh Warden, who also lived in Alyth and I do wonder whether he was involved.

Very Curious Descendant, John Christie.

Seeing John Christies comment about his relative and his trial following the battle at Culloden and having relatives of my own living in the area at the time I wonder if there were any Christie’s involved in the battle or were captured and tried.

Very interesting article. Thank you.