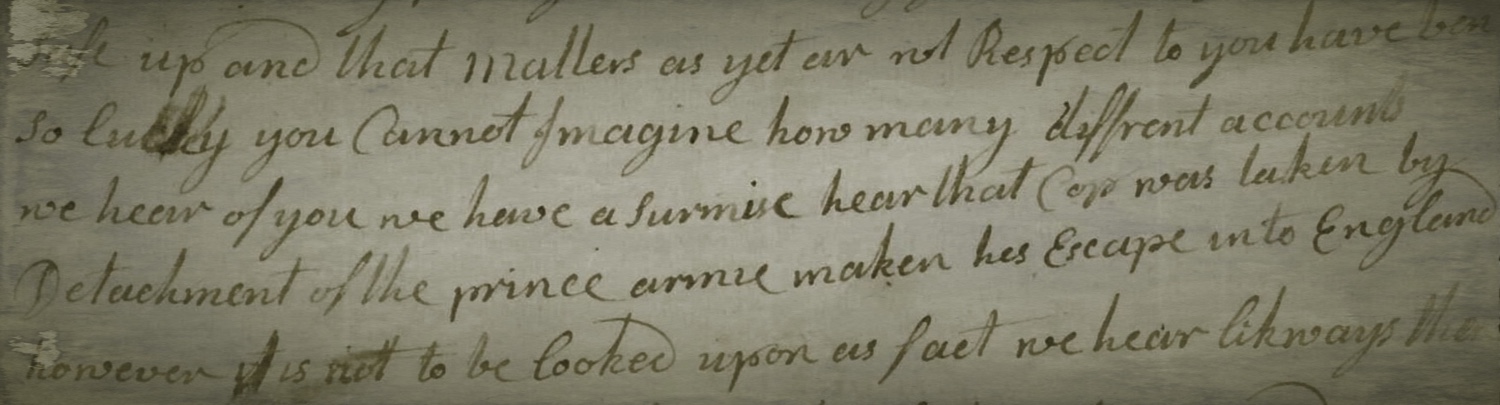

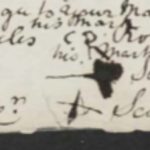

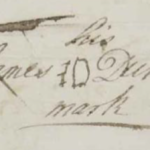

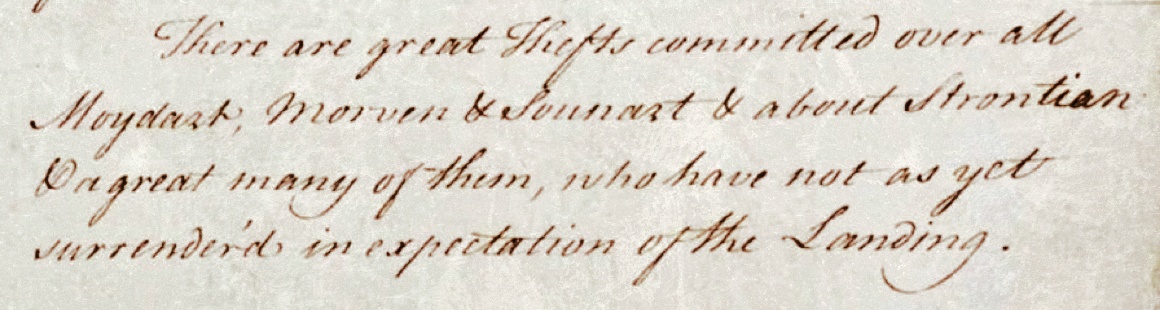

Of the many archival sources relating to the last Jacobite rising that still survive, one category of documents that is noticeably thin is that of personal letters from rebel soldiers. This makes sense for a number of reasons. For one, the army led by Charles Edward Stuart was almost constantly on the march during its eight-month campaign in Britain, leaving little time to write to family back home. Literacy among the rank-and-file troops was not particularly pronounced, and this is borne out by the number of Jacobite prisoners who claimed they could not write, instead leaving ‘their mark’ on government documents in place of a signature. Postal service through the Royal Mail and by private couriers was indeed active during the crisis, but was notoriously unreliable due to poorly maintained roads through often difficult and remote terrain, as well as the fact that the kingdoms were in the midst of a civil war. Packets of sealed letters were regularly seized by agents on both sides of the conflict and were broken open in the search for seditious material and intelligence within.1 As a result, thousands of missives never made it to their final destinations.

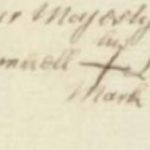

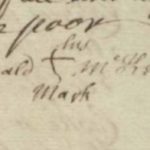

The signature marks of numerous illiterate Jacobite prisoners and witnesses against them

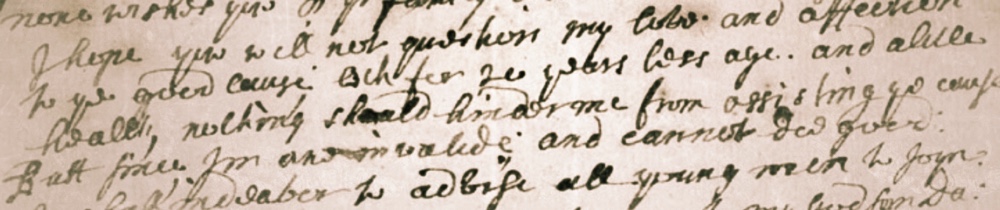

This dearth of important evidence means that it can be a bit more difficult to study the context of the common people who were caught up in the rising, both within the Jacobite army and on the home front. Newspapers and magazines of the time were valuable for getting out basic (and sometimes pointed) information to the masses, but they are nowhere as intimate or revealing as the personal letters themselves. Thankfully, a few significant collections of these letters written by plebeian soldiers and their family members are still preserved in various archives, and they shed a fascinating light on what it was like for some of the ‘ordinary’ people in Britain who were involved – willingly or not – in Jacobite designs during such a tumultuous period.