In the days and months after the bloody defeat of the Jacobite army at Culloden, the British government scrambled to obtain evidence of anyone and everyone who might have taken part in the rising. In addition to calling upon the extensive network of Presbyterian clergy spread across Scotland to be their eyes and ears, British officials instructed both local administrators and individual landholders alike to create rosters of those known to have refrained from treasonous behavior. A cagey measure that was no easy task for either regional authorities or private factors to accomplish, this method of information gathering would nonetheless yield a significant number of names for government prosecutors, in turn giving them a robust pool of leads into which to launch their investigations. Indeed, anyone not recorded in these lists of certified abstainers was essentially fair game.1

In addition to soliciting lists of those who were thought to be ‘safe’, customs officers at both major and minor Scottish ports were required to tally registers of travelers known to have Jacobite inclinations, as well as those who were believed to have actually carried arms in the rising.2 Despite their appearance in writing, of course, not all of the included names were of men and women who were actually involved. A great many were jotted down by authorities and subsequently hauled in on suspicion alone, but most of these were soon set free due to lack of evidence or other exculpatory testimonies. Others were included due to faulty evidence from witnesses who simply got it wrong, and some were falsely implicated by those with distinct agendas. After all, what better time to strike at a personal enemy than during the chaos and confusion of civil war?3

Adding to these intelligence efforts, some heritors and chiefs, with an eye toward being ‘extra helpful’ to the government (perhaps hoping to bolster favor and allay any suspicions of Jacobite complicity), included the names of those living upon their estates who were known or considered to be rebellious, either in action or disposition. Many of these lists are still preserved at archives in both Scotland and England, and only some of the names they contain have been heretofore included in published studies of the Jacobite constituency. Estate rosters of this kind were sent in from all corners of the country, and extant documents can be seen from places like Montrose, Fraserburgh, Kincardine, and Appin, just to name a few.4

This week’s post takes a closer look at one of these accounts: a list of persons living in Appin and Glencoe written up and sent to Justice Clerk Fletcher by Dougal Stewart, the 10th Chief of Appin. Though the region contributed a regiment bearing its name to the Jacobite effort in 1745, its titular chief was not at the head of it. Instead, it was his uncle, Charles Stewart of Ardshiel, who led the Appin men at the request of James Francis Edward, himself. There is some uncertainty as to what role Dougal Stewart played in the rising, if he indeed played any part at all.5 But we do know that by the middle of June 1746, he had written a memorial to Fletcher, wherein he defended his position while at the same time breaking down exactly which of his tenants were guilty of treasonous activities.6

The chief’s appeal is a fascinating work of prevarication and blame-deferral, even if it resembled anything close to the truth. Within it, Dougal explains that, due to his rearing in the Lowlands of Scotland and in England, he had no real understanding of Highland ‘Clannishness’ and this made him somewhat of a pariah – or at least wholly alien – to the majority of his tenants, many of whom were family. He had done his best to prevent them from taking up arms with the Jacobite army, but there was only so much influence he wielded there. Besides this, a significant number of men who joined the Appin regiment were from lands outside his purview and, therefore, his responsibility:

My Lord, it seems to be a general Mistake, that all who had join’d the Rebels of Appine were from the Country of Appine, but I can assure Your Lordship that there were no more of my Tenants in the Rebellion than 21, the others who were said to be of that Corps, as I amcredibly inform’d, having been from Balquhidder, Monteith, etc., in which parts I have neither property nor Influence.7

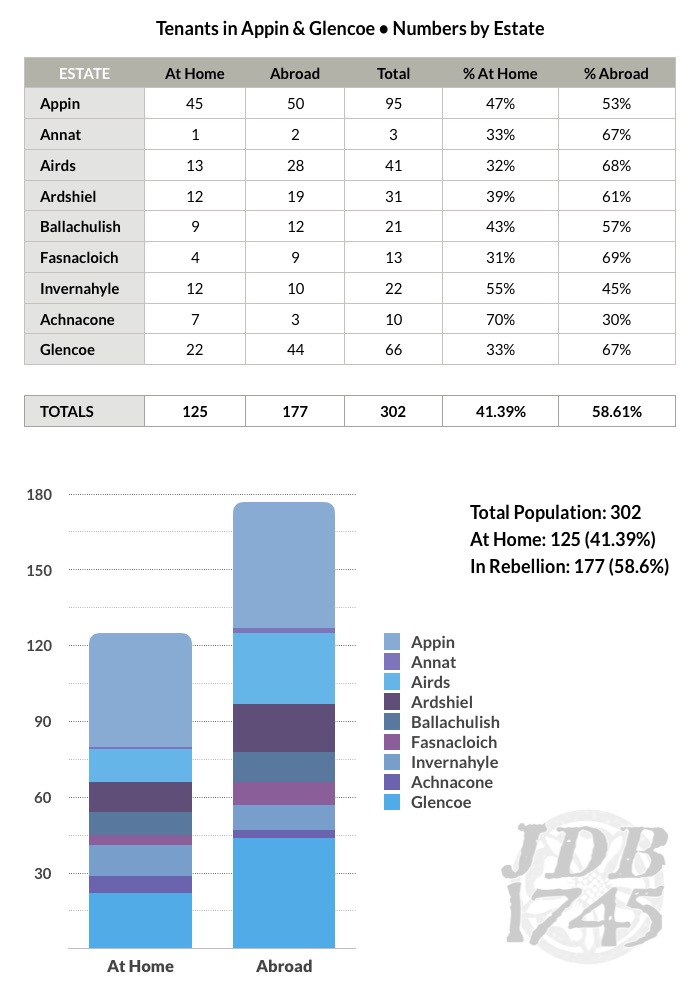

Of the 302 names of Dougal’s tenants across the different tacks of his estate in Appin and Glencoe, where he did have some measure of influence, the chief thanks God that only some of them joined the rebels, and that only slightly more were eventually ‘seduced’ from home.8 As shown in the chart and graph below, according to Dougal’s list, 177 of his tenants left to join the rising while 125 remained behind. Broken down by major tacks, we see a general trend of slightly more tenants favoring the Jacobite cause than not, with estates like Appin, Airds, Fasnacloich, and Glencoe being substantially inclined toward the rising. Conversely, only the Invernahyle and Achnacone estates feature more tenants who stayed at home than those who joined up with Charles Edward Stuart, and those only by a few. Still, the overarching conclusion based upon this data is that loyalties, even in areas which definitively produced substantial regiments for the Jacobite army, were strongly divided.9

Naturally, there are numerous reasons why the information that Dougal provided might not be either accurate or complete. As the accompanying memorial to Fletcher takes such a defensive stance, it is not out of bounds that the marginalized chief had something to prove to the government, though whether he was actually a Jacobite agent cannot be inferred from these documents alone.10 To this end, we must test the composition of his roster by further tracing the fates of the men included, as well as comparing contextual sources of habitation and Jacobite activity in the region.11 It is possible that Dougal Stewart was either inflating or suppressing evidence of Jacobite activity on his estates, and indeed he would have legitimate cause to do both. Similarly, we do not know whether those who remained at home otherwise contributed to the Jacobite logistical or intelligence efforts despite their lack of military participation in the rising itself.12 Hence there are limits to what this data tells us about the disposition of the Appin and Glencoe estates during the rising.

Likewise, the region shown in this study cannot be taken as a standard indicator of the pervasiveness of Jacobitism in Scotland. Though different areas of the country were divided with varying degrees of support for the Stuarts, tolerance of the Union, and comfort with the Presbyterian primacy, the magnitude of the Forty-five as a social and military movement was relatively small. The laird of Appin’s list may show nearly 60% of his tenants in arms for the Jacobites, but across Scotland the generous extent of martial support was a little over 1% of its total population.13 Other areas confirm wildly divergent ratios with fluctuating trends as the fortunes of the army degraded through the campaign; whereas we can confidently track around 2100 Jacobite adherents (both civilian and military) from Angus in all of 1745-6, places like Argyll furnished only around 250, and smaller populations like Caithness and East Lothian likely contributed but fifty to seventy known supporters each.14 Further analysis may be undertaken by comparing census and valuation rolls both before and after the rising with the many lists of known participants.

As the names in this list pertain to the historical record of the Jacobite constituency, a few analytical notes are illustrative. Of the 177 names on Dougal Stewart’s roster of tenants whom he claims were involved in the rising, at least thirteen of them have not been included in published rosters of either the Jacobite army or its prisoners, including the latest printed iteration of the problematic muster roll, No Quarter Given (Glasgow: 2001). Two-dozen additional names are absent from Seton and Arnot’s seminal compilation, The Prisoners of the ’45 (3 vols., Edinburgh: 1929). In addition, the compilers of the muster roll have made numerous errors in recording the home origins of some of these men, like Duncan Mcilireoich (likely Mcilroy or MacHerioch), who is cited as hailing from Achosregan on Appin’s estate when the landlord himself clearly shows that the man was a vassal of Stewart of Invernahyle’s at Inverfolla (written as Inverfoullay in the document). Furthermore, a large number of names from the list are consigned to either the Appin regiment or the Macdonalds of Glencoe in the muster roll, which is frustrating due to the fluid nature of Jacobite regimental organization during the Forty-five. The Glencoe men, for example, were merged with the Macdonells of Keppoch shortly after Prestonpans and would remain attached for the remainder of the rising.15 These omissions, errors, and inflexible printed groupings collectively open the door for a modern reinterpretation of Jacobite participation from Appin and Glencoe and well beyond.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and Open Access.

Thank you for this excellent analysis of this Muster Roll. I have used this Muster Roll and the “Stonefiled List” as examples of why there were no Balquhidder McLarens in The Stewart of Appin Clan Regiment. I have also found issues with No Quarter Given, specifically concerning the Capt. Donald McLaren of East Invernenty listing in the Appin Regiment. I am the 6x Grandson of Duncan Mclarine on the Invernayhle estate. Duncan’s father is Lauchlane Mclarine at Blarnaloe. Duncan emigrated to North Carolina and died in 1809, buried in Stewartsville Cy. in Scotland Co. outside of Laurinburg, NC I am… Read more »

Many thanks for your engagement, Hilton, and for your notes regarding some the Appin men. I’ve seen no evidence to definitively support the active partitioning of a designated ‘home guard’ in Appin or Glencoe during the Forty-five, so I wouldn’t yet feel comfortable attributing their remaining behind to that utility – especially if, as you say, Appin’s influence over his tenants was in question. I also believe that numerous non-political motivations came into play when it came time to either join or abstain from the rising. Sussing out those motives is a big part of what my work attempts to… Read more »

On the question of the MacDonalds of Glencoe initially mustering with the Stewarts of Appin, (1) Appin was the feudal superior of Glencoe, (2) Appin’s half sister Isobel was, from recollection, married to the Chief of Glencoe and (3) Donald Campbell of Octomore wrote to Archibald Campbell of Stonefield, Sheriff Depute, from Castle Stalker on 20 July 1746: “There was some Bargain or other of a part of the Lands of Glenco between them by which Appin was obliged, among other things, to make Glenco his Lieut Coll. – He knows everything about Appin’s conduct and if he would not… Read more »

Very much appreciate this helpful information, Angus. You’ll see the many references to your work in the citations above, as well as to that cracker of a letter between Octomore and Stonefield.