There was a fair bit of commotion upon the mercat cross of Coupar Angus one mid-October day in 1745. Bailie Charles Hay, a locally known clerk and town magistrate, stood at the nexus of George and High Streets with a copy of Charles Edward Stuart’s manifesto and read it aloud to a rapidly assembling crowd. This was an overtly treasonous act by a man widely thought to have been loyal to the British government of George II. But as the ruckus played out, witnesses would allegedly see a number of prominent Jacobite personalities join Hay on the cross and physically compel him to address the busy town centre on behalf of the exiled Stuarts.

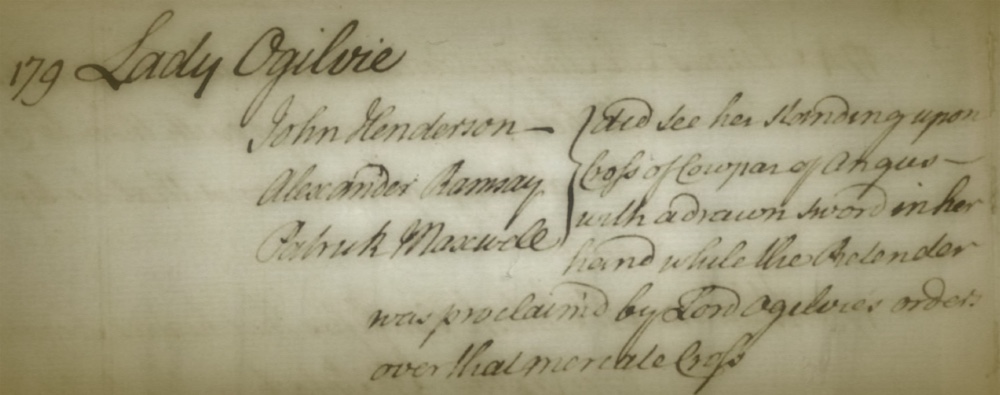

According to some of the townspeople who were present, the Lord of Airlie himself, David Ogilvy, stood beside Hay with a sword in his hand, making certain that the bailie got it right and explicitly proclaimed James VIII & III as the rightful ruler of the three kingdoms of Britain. Also there on the cross were two sons of Sir John Ogilvy of Inverquharity, Thomas Ogilvy of East Miln, Charles Rattray of Dunoon, and Airlie’s wife, Margaret Ogilvy. All of them, including Lady Ogilvy, were alleged to have had their swords drawn and either pointed at Hay or held above his head as he hoarsely read out the terms of the Jacobite occupation.1

Dozens of citizens amongst the town’s population of 1500 would relate a similar story to government officials in the wake of the last Jacobite rising. It is a collective tale wherein the ‘Queen of Strathmore’ was occupied by rebels converging from all parts of Scotland through the autumn and into winter as the movement gathered considerable momentum.2 Their depositions describe disturbed routines, stolen carts and horses, and town magistrates pressured to act on behalf of the Jacobites, usually, but not always, against their wishes.3

By the end of the harvest, elements of the Jacobite army had already been billeted upon the town for several weeks. It was a strategic waypoint situated at the center of a rhomboid expanse with Perth to the southwest, Dundee to the southeast, Forfar to the northeast, and the mountainous regions of Glenisla and Atholl to the north and northwest. For the Jacobite army, Coupar Angus functioned as a gateway to the region of Scotland that provided one of its largest concentrations of military support: the heavily Episcopalian north-eastern counties of Angus, Aberdeenshire, and Banffshire.4

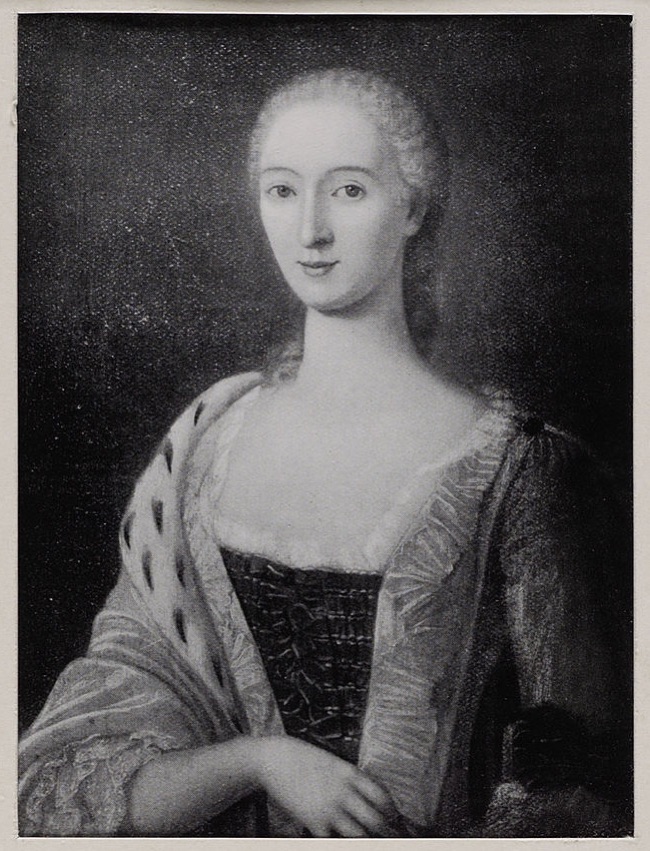

The scene at the mercat cross was one repeated in many towns in Scotland as the Jacobites established their logistical networks and scoured the localities for recruits.5 What made Coupar Angus stand out is that the wife of an elite Jacobite lord and regimental commander, Margaret Ogilvy (née Johnstone), was embedded with the army there and was seen to be bodily involved in imposing Jacobite authority upon citizens of the medieval town. There are many other notable tales and anecdotes of Jacobite women who were involved in the rising of 1745; some are supported by limited evidence while others are apocryphal or embellished for shock value that furthers contemporary government propaganda about the very nature of their contribution.6 Ogilvy’s exploits, however, are corroborated by several eyewitnesses and the local government’s reaction underscores the threat she represented not just to Coupar Angus, but to the perceived integrity of an orderly Georgian society.

George Miller, the dutiful sheriff-deputy for Perthshire, was responsible for organising the prosecution of many hundreds of Jacobite prisoners in the county through much of 1746. After taking on a docket of inflammatory depositions in July of that year, he became incensed at the audacity of Lady Margaret and insisted to Everard Fawkener, the duke of Cumberland’s secretary, that she must be brought to justice at any cost, writing ‘…this impudent Lady ha’s been using a drawn Sword in her delirious Zeal for Hell, France, Rome & the Pretender & if She & Such as She escape unpunished, Heaven will resent it on us’.7 Miller’s reaction is emblematic of the popular societal projection that these Jacobite women were operating well outside what was deemed to be acceptable for their gender.8

‘…this impudent Lady ha’s been using a drawn Sword in her delirious Zeal for Hell, France, Rome & the Pretender & if She & Such as She escape unpunished, Heaven will resent it on us.’ 9

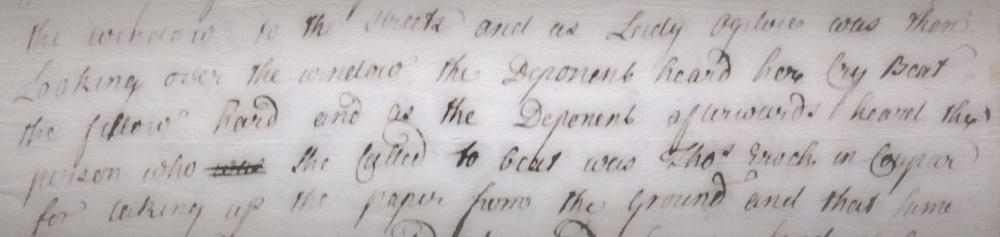

Margaret’s sword-wielding at the expense of Charles Hay was not the only ‘outrageous’ behaviour of note during her stay in Coupar Angus. On the same day, she and her husband entered vintner David Clark’s home and ripped down a poster that featured the face of King George stamped upon it before throwing it out the window and into the street. Clark went on to depose that Ogilvy saw through the same window a man named Thomas Eroch pick up the poster, at which point she called out for passers-by to ‘Beat the fellow hard’ – perhaps unexpected words from a noble woman of means.10 She would go on to accompany Ogilvy’s troops to England the following month, returning with them to Scotland in December and eventually being captured near Inverness shortly after Culloden the following April. Judicial records suggest that, as the wife of a Scottish peer, government ministers were not even certain she could be prosecuted in England like the rest of the Jacobite prisoners were to a person. Margaret made sure the issue remained moot, as she carried out a rare escape from Edinburgh Castle that November with the help of family, servants, and not a small measure of subterfuge.11

Lady Ogilvy’s contribution to material Jacobite efforts during much of the rising plausibly puts her on level ground with some of the more mythologised characters of the Forty-five like Jenny Cameron and ‘Colonel’ Anne Mackintosh, both of whose adventures are the stuff of legends but are difficult to definitively verify in the archive. While Charlotte Robertson of Lude’s and Mary Hay of Errol’s recruiting efforts share a more robust paper trail, Ogilvy appears to have also contributed to the rising through a number of additional activities, including enlisting soldiers for the Forfarshire regiment, enforcing Stuart proclamations in public spaces, and fundraising for the Jacobite martial and political efforts. Indeed, evidence suggests that Lord Airlie relied upon her for these efforts.12

In Margaret Ogilvy’s case, the numerous eyewitness accounts of her actions while in Coupar Angus collectively paint a compelling picture: a ‘female rebel’ of significant status who aggressively demonstrated her commitment to Jacobitism by her own hand. She clearly was, unlike Hanoverian propaganda would have us believe, much more than simply a matrimonial ‘accomplice’ to the political aspirations of her husband or a ruthless sadist intent on exacting retribution upon loyal subjects of George II.13

This article first appeared in the Sep/Oct issue of History Scotland (Vol. 21 No. 5, pp. 36-7)

as part of its Spotlight: Jacobites column.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people who were involved in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the protean nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and accessible research.