According to the testimony of Joseph Bruoden, a musician in Manchester at the time of the Jacobite army’s arrival there in late November of 1745, he was bullied into joining the rebels at gunpoint. This was not an infrequent claim from those captured by the government during and after the final rising. When faced with the charge of high treason in the London courts and its consequential punishment by death, it only makes sense that terrified prisoners would swear they were compelled by force to pick up arms against the Hanoverian king. It was, in essence, a Hail Mary in favour of their very survival.

So many had claimed impressment, in fact, that most scholars strongly marginalize the significance of its presence, holding to the traditional maxim that such claims were not only the norm and therefore are patently untrue, but that they exacerbate the perceived severity of the Jacobite army’s recruitment tactics. After extensive collation and analysis of both impressment claims and cases during the rising, my own findings contradict this marginalization, instead suggesting that the last Jacobite effort was effectually decentralized and hardly popular, and the need for armed supporters was so great that coercion – by fire and sword, through financial or emotional manipulation, or simply at gunpoint – was markedly rampant during the affair.1

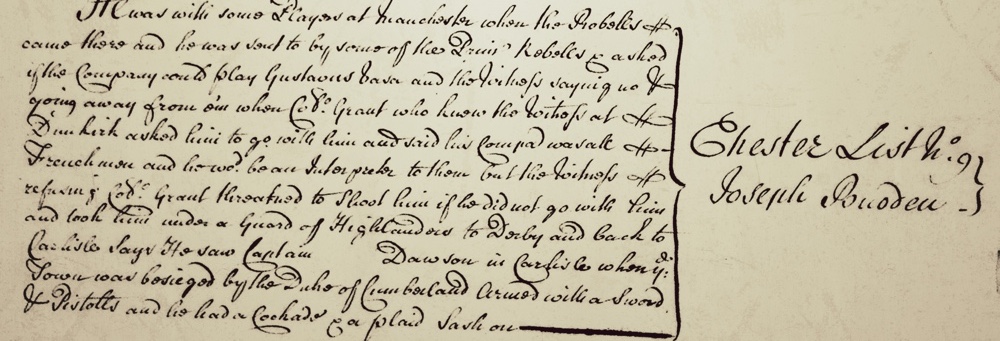

He was with some Players at Manchester when the Rebells

came there and he was sent to by some of the Princes (Privt?) Rebells & asked

if the Company could play Gustavus Vasa and the Witness saying no &

going away from ‘em when Colo Grant who knew the Witness at

Dunkirk asked him to go with him and said his Compa was all

Frenchmen and he wod be an Interpreter to them but the Witness

refusing Collo Grant threatened to Shoot him if he did not go with him

and took him under a Guard of Highlanders to Derby and back to Carlisle…2

Bruoden’s experience is illustrative. Approached by Jacobite recruiters, his band of French ‘players’ was asked to provide some entrainment in the form of an outlawed musical: Brooke’s anti-Walpolian Gustavus Vasa. Knowing the significance of that piece, or perhaps just being leery of Col. Grant (likely James, whom Bruoden apparently had met earlier in France), he refused and tried to put some distance between the two ‘bands’. Grant was resolute, insisting that Broden would be a welcome addition as the interpreter for his company of French Jacobites. This was not posed as an option.

Under threat of being shot, Joseph Bruoden was taken under guard by a troop of Jacobite soldiers (‘Highlanders’) and brought along with the rest of the army to Derby. There, as we know, Charles Edward Stuart was himself coerced – though not through violence – to enact the retreat back to Scotland by his council of commanding officers. Shoring up for a last stand at Carlisle, likely with the Manchester Regiment, Bruoden was captured when the town surrendered to Cumberland’s troops on 30 December 1745. From there, we only know that he gave evidence against Captain James Dawson of the Manchester Regiment, who was later executed at Kennington Common, 30 July 1746. What then happened to Bruoden has not yet been unearthed.

It is somewhat surprising that the few existing studies of Jacobite prisoners have not made better use of the extensive Treasury Board Papers at The National Archives. While there is some overlap of names in the usual secondary sources (The Prisoners of the ’45, The Muster Roll of the Jacobite Army, A List of Persons Concerned in the Rebellion, etc.), I have not yet seen any significant work done with the actual deposition and trial records of those accused, other than a handful of reprinted transcripts on specific high-profile Jacobite proceedings. The wealth of information contained within this collection (and others like it), if catalogued and analyzed properly, could significantly contribute to – and perhaps even modify – what we know about the social history of Jacobitism in the mid-18th century. That is precisely what my current project seeks to flesh out.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata organization, and Open Access.

I am researching the involvement of the Mitchell families in the Jacobite Rising of 1745 following a suggestion that there is a family connection. I am using FindMyPast and have come across numerous ~Mitchells mentioned in papers from the PRO. Many of these are not mentioned in books. Intriguingly there is a Mr Mitchell who was classed as a spy!

Indeed, Susan, there are lots of great leads to be found in the archives. Wishing you all the best with your research!