Much of the enduring memory and emotion of the final, failed Jacobite challenge blooms from the British government’s retributive and bloody response in the aftermath of Culloden. In what Allan Macinnes calls the ‘exemplary civilizing’ of remote areas of Scotland, a calculated campaign of violent suppression was waged upon recalcitrant communities whether or not they were directly involved in active rebellion.1 Whether tantamount to genocide, as some scholars have argued, the cantonment schemes established in Culloden’s wake and the retaliatory expeditions against communities singled out by government intelligence networks undeniably had a disastrous effect upon ‘Scottish Highland’ culture, though these depredations were not by any means meted out only in the Highlands.

Such machinations went largely unnoticed by the general populace of Britain and were in fact often covered up by propagandized reports of the Duke of Cumberland’s ‘paternal way’ and his willingness to forgive those who might submit to the government for mercy.2 The administration of George II was indeed concerned with presenting a public facade of reasoned clemency even as it organized ‘state-sponsored terrorism’ against many of those whom they perceived to be the foreign ‘other’ existing within the technical boundaries of the British nation. Judging by the documents left behind, the overriding mood of government officials in the latter half of 1745 was more often than not one of righteous disbelief that somehow, some way, yet another Jacobite-instigated rebellion was taking place at home. An ‘unofficial’ policy of repression to decisively prevent any further disorder was accordingly not all Cumberland’s doing, however enthusiastic he was to enforce it in Scotland.3 For his ruthless actions after Culloden alone, it is no wonder that Cumberland has received the brunt of the historical and memorial resentment. While many historians are fond of citing particularly aggressive quotations penned by ‘The Butcher’, however, other missives suggest his station was predetermined and, racist and condescending rhetoric notwithstanding, that the distasteful job with which he was tasked was not necessarily something that he always relished:

I indeed do that justice to my friends that they feell my disagreable situation at the same time that it is found necessary that I should ingage and go through with the affair, which I now hope is almost over with regard to the Military operations, but the Jacobite rebellious principle is so rooted in this nation’s mind that this generation must be pretty well wore out, before this country will be quiet.4

Though a comprehensive, comparative modern study of the many schemes and outlines for policing Scotland from 1745 has yet to be compiled, plenty of extant documents give us some sense of the practical stratagems laid upon the collective table of Hanoverian government officials after the rising had finally dwindled out.5

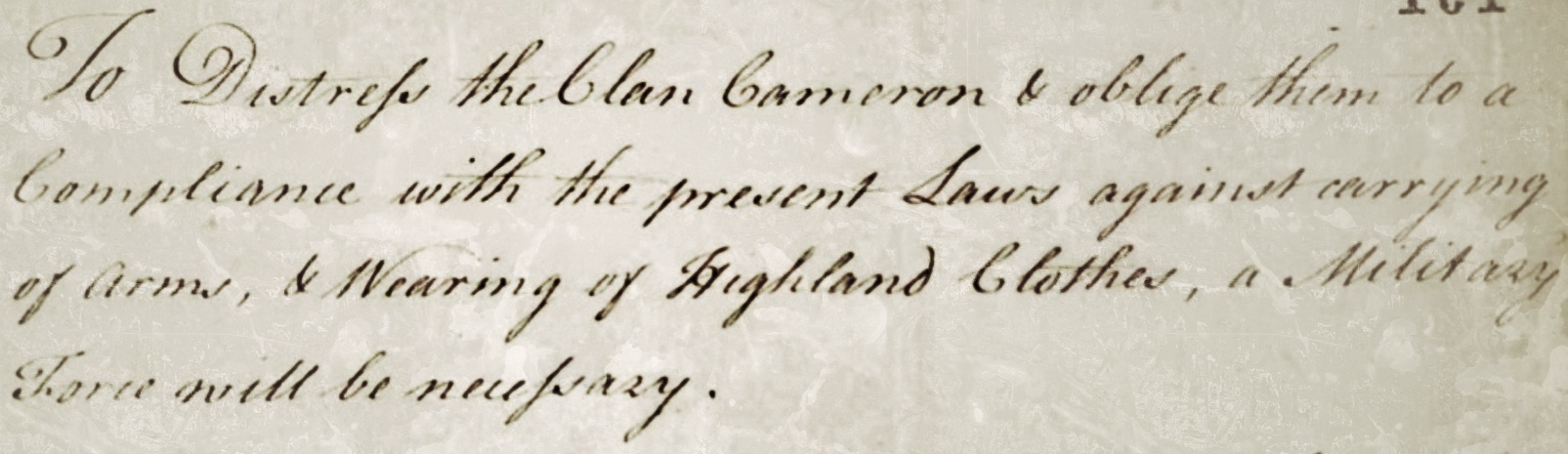

In what should extinguish the queer notion that the cantonment and oversight of Scotland was purely an English tactic to subdue its northern neighbor, we see many of these schemes actually drawn up by Scotsmen – Highlanders, in fact – who remained loyal to the established Whig order. Alexander Robertson of Straloch, the dutiful spy from Atholl known as Baron Reid, submitted two memorials to the Duke of Newcastle’s secretary that painstakingly calculated the most efficient placements ‘for the particular Stations of the Troops which I hope will make the matter Easie and prevent disturbances’.6 John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun, raised twelve Highland Independent Companies in service to George II and was tasked with capturing Charles Edward Stuart during his flight through Scotland after Culloden. His orders to Macleod of Bernera and Munro of Culcairn contained elaborate strategies for the placement of soldiers to hamper both Jacobite activity and common banditry in the Isles.7 And, illustrated in the document above, Donald Campbell of Airds was frustrated enough by the recalcitrance of his Cameron neighbors in Lochiel’s country to lobby for a remedy focused around active garrisons of British army infantry to force a semblance of ‘peace’ in Argyllshire.8

In this plan, Campbell proposes to Lord Albemarle and Lord Justice Clerk Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun a scheme of six cantonments of over 400 men most effectually situated ‘to distress the Clan Cameron and oblige them to a compliance with the present laws’. He lists them as follows, with notes about distances between garrisons and the suitability of accommodation for the men:

• 100 At Strontian

• 70 Head of Lochiel

Distant from Strontian 9 Miles

• 100 Head of Locharkaig – Requires a strong party, as Bordering on Knoydart & the McDonald’s Country

Distant from the head of Lochiel 6 Miles

• 50 Lochiel’s House at Auchnacarry

Distant from the head of Locharkaig 12 Miles

• 50 High Bridge

Distant from Auchnacarry 4 Miles

• 60 Kenlochbeg & Achatrichadan in Glencoe

Distant from High Bridge 12 Miles

Total: 430

Campbell of Airds was one example of the many Highlanders who stood to benefit from greater military control in certain areas of Scotland. A factor to the Duke of Argyll, the Appin territory in his charge bordered that of Cameron of Lochiel’s in Lochaber, whose clansmen were of course prominent players in the Forty-five. The fierce and venerable enmity between Camerons and Campbells was further stoked during the rising when homes along this border were burned and looted by government troops. Lochiel and Alexander Macdonald of Keppoch held Campbell of Airds responsible for conspiring with Cumberland to destroy farms in Morvern and vowed revenge for their ‘cowardly barbarity’.9 The intention for these expeditions was, apparently, to keep potential rebels at home and to bring back others who had joined the Jacobite army, and was ordered as early as August 1745, when the rising had just begun. Certain Campbells of note, including Craignish and Stonefield, appeared to believe these tactics had at least in some part been successful.10

As a loyal government operative, Donald Campbell of Airds served as a captain in the Argyllshire Militia and since the very beginning of the rising had provided valuable intelligence on rebel movements through the county. He claimed to have raised some of the first Highlanders to fight for the government in the campaign and later undertook a recruiting mission in Mull, however paltry the return.11 By the spring of 1746, he was chasing the Jacobites around Aberdeenshire while his own steadings in Kilcolmkill were being plundered by the men of HMS Serpent, who took away nearly 150 animals and looted and burned to the ground eleven structures including three dwellings, a kiln, and a corn-mill.12 He fought at Culloden and returned home to monitor the Camerons and the Appin Stewarts, continuing to provide intelligence on rebel activity into 1748.

Campbell was still petitioning the Duke of Argyll for recompense in the first quarter of 1750, seeking restitution for the considerable damages inflicted upon his property. Though he was usually paid by General Huske and Lord Albemarle in a timely manner for his intelligence work, Airds was particularly galled that his superiors were trying to get out of it by claiming that so many of the king’s subjects had claimed losses in the rising that there was simply no way to repay each and every case. He reminded Argyll that these were not damages inflicted by Jacobites, but by men of the British army, whom he had enthusiastically aided since Charles Edward first had landed in 1745:

…the Depredations for which he claims Redress, committed, not by the Rebels, but by Part of the King’s Forces, mistaking the Memorialist’s for rebel Lands, his farm of Kilcolmkill being unluckily situated betwixt Stewart of Appine & Stewart of Ardsheal their Dwelling Houses.13

The amount requested by Airds came to just under £300 for the losses of his livestock, structures, furniture, and stores, with another £115 in lost rents from 1745 to 1749 due to the burning of his tenants’ dwellings. Along with his reasoned petition to Argyll is a copy of the orders from Robert Askew, who commanded the sloop Serpent from which the Appin raids were launched. Askew explicitly stated that his men were to ‘destroy & bring away what Cattle you can’, which was bulletproof evidence that Campbell’s losses directly resulted from government policy.14 Such policy was in fact not so very uncommon in the Western Highlands, as conveyed in the intelligence report of Patrick Campbell, just back from his survey of the area in the late autumn of 1746. Within this report, amongst other dismal vignettes, he describes large swathes of burned land, including fourteen villages in Morvern and six in Appin, and cattle taken from Stewart of Ardsheal’s estate by none other than Campbell of Mamore himself.

The reality of the situation was that the close proximity between loyalist and Jacobite in this area of Scotland, in particular, made it quite a messy affair. As we shall see in the next post on Little Rebellions, Patrick Campbell’s account led prominent government supporters to be very concerned about continued violence, whether that be from sustained Jacobite activity or from general lawlessness. Airds’ scheme of garrisons reasonably addressed the issue, as he had witnessed the rancor firsthand and retained the fallow fields and charred foundations to prove it. His goal in helping to establish these outposts was to ‘apprehend such Rebel Gentlemen as are yet lurking in Lochiel’s Country, And preventing their making depredations on their Neighbours who are Loyal Subjects’. The great irony here, of course, is that the particular damages on his estate were inflicted by the very class of men whom he proposed should protect the region going into the future.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and Open Access.

[…] last post explored some examples of the Highland cantonment schemes proposed by British government officials after Culloden, their […]