The collective social power and reach of the parish minsters in the Presbyterian Church of Scotland was one of the British government’s most potent weapons in quelling the last Jacobite rising.1 These ministers, in addition to being sanctioned recipients for the submission of illegal arms and an integral part of the extensive information network employed to identify alleged rebels, were some of the only people in Scotland that some prominent members of the military felt they could trust.2 Alexander Melville, 5th Earl of Leven, who was High Commissioner of the General Assembly during the Forty-five, remarked to Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle and Secretary of State, at the end of May 1746 that the loyalty of the Scots clergy was exemplary, and despite ‘the smooth arts of flattery & cajoling’ used by the Jacobites to gain their trust, only two specific ministers were known to have any sensitivities to the cause.3

Tag: church of scotland

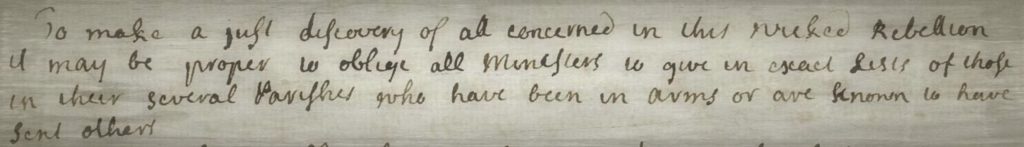

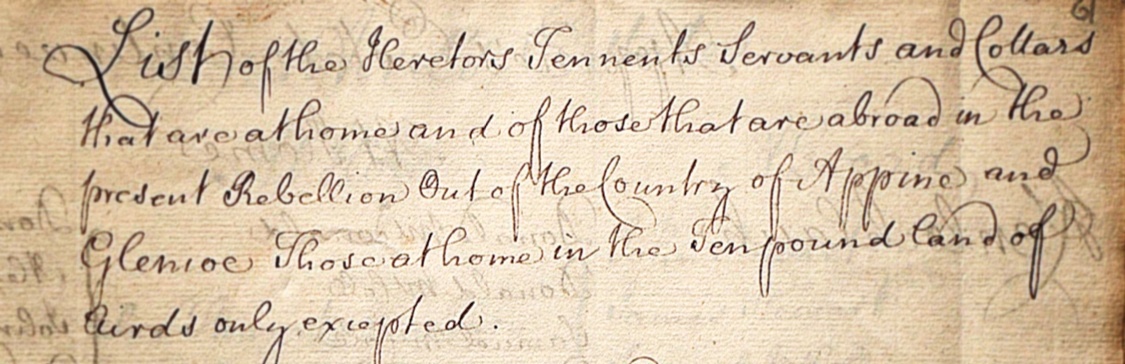

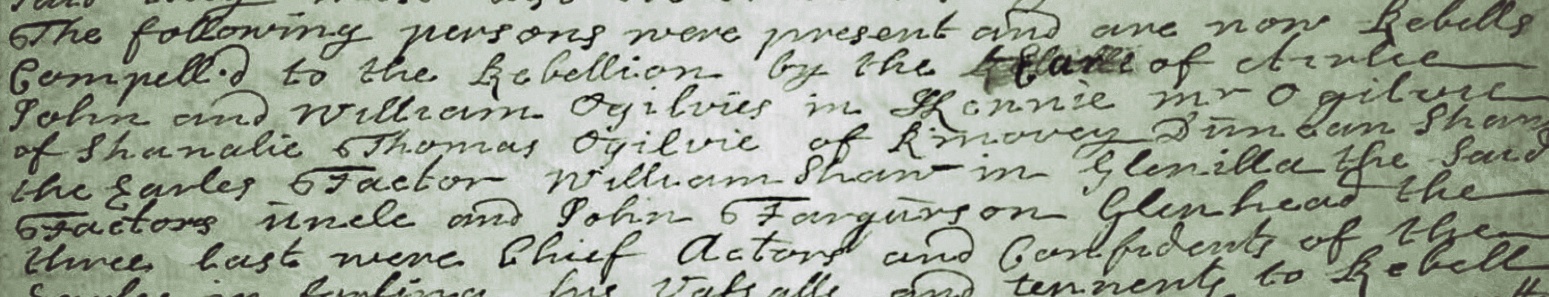

In early December 1746, well after the active threat of the last Jacobite rising had waned, the British government was still collecting intelligence regarding known rebels who had not yet been apprehended. The report of Alexander Robertson of Straloch from that month, presumably sent to the Duke of Newcastle, is especially interesting for two specific reasons. First, it explicitly calls out the forceful tactics of impressment used against unwilling tenants on David Ogilvy, 6th Lord Arlie’s estate. Second, within it Straloch proposes an elaborate plan to trick lurking Jacobites into revealing themselves – a plan that is both impressively calculated and devious.7

Known informally as Baron Reid, Alexander Robertson of Straloch was a gentleman from the Strathardle area of Perthshire whose family had long been aligned with the house of Argyll and the Hanoverian government. He was a vassal of James Murray, the loyalist Duke of Atholl, and he spent much of the rising assisting the government by providing intelligence reports and offering counsel regarding methods to suppress the rebels.8 Straloch was evidently quite well connected during the Forty-five, corresponding directly with Newcastle – the secretary of George II – and Duncan Forbes of Culloden, the Lord President of the Court of Session. To these officials he sent a series of bulletins between 1745 and 1747 leveraged from the network of Presbyterian ministers in Perthshire and the north-east who received and conveyed useful intelligence about Jacobite movements.9 Straloch was effective enough as an informant to warrant a mandate for capture from Atholl’s brother William, the Marquess of Tullibardine and titular Jacobite Duke of Atholl.10

© 2026 Little Rebellions

Modified Hemingway theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑