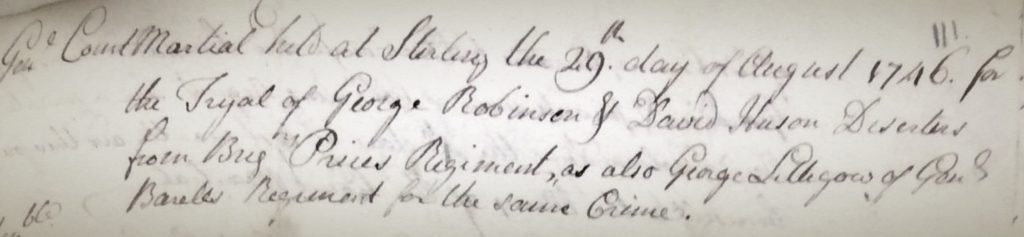

Amidst the complexities of dynastic opposition and civil war during the later Jacobite era, the loyalties and material commitment of individuals were often in flux and have not always been so simple for historians to cleanly define. Allegations of significant Jacobite desertions have long been suspected (and more recently have been examined), but little scholarly enquiry has been made into cases of defection by soldiers within the government forces who were charged with quelling the Jacobite threat in Britain during the ’45.1 Resistance to martial service permeated both sides of the conflict, but deserting ranks to avoid combat is one thing, while joining up with the enemy is another entirely. Archival evidence shows us that soldiers in British service – including loyalist Highlanders on campaign in Scotland – deserted their units in smaller numbers than their Jacobite rivals, but incidents of soldiers breaking ranks was still a problematic issue for British army officers and Hanoverian officials.2 Digging deeper into the sources further reveals that some of these deserters found both cause and motivation to fight amidst the ranks of Jacobite rebels.

Tag: motivation

If you had been able to walk the lines at Culloden around noon on 16 April 1746, about an hour before the Jacobite cannons opened up, with enough time to ask a few questions about why the rebel soldiers were ranked up there on that frigid and rainy day, you might get a number of different answers.

It could be somewhat difficult to understand some of the responses, as representatives of numerous countries and localities were present on the field, including many native Gaelic-speakers from the rural Highlands and Islands. Murdoch Shaw, standing at the centre of the Jacobite front line, would tell you that he was brought to Culloden by his master, Alexander Macgillivray of Dunmaglass, who served as a leader of Clan Chattan in the Forty-five.1 It was customary for men of stature to bring servants into battle so their horses and baggage could be kept in order, but some of these attendants were also expected to fight alongside them.2 Shaw’s chief would perish in combat shortly after your conversation with him, at just the tender age of twenty-six.3 On the left flank of the Jacobite vanguard, Donald Bain Grant huddles with men from the different clans serving in Macdonell of Glengarry’s regiment. He might describe to you how he was taken forcefully from his home in Corrimony by desperate Jacobite recruiters just the day before, and that he was quickly rushed to Inverness in anticipation of the coming engagement.4

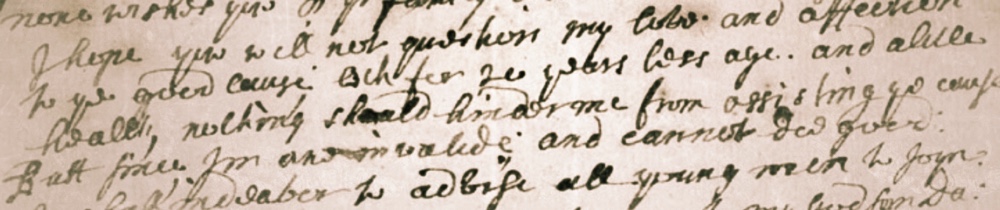

I hope yew will not question my love and affection to ye good cause. Och for 20 years less age, and a little health, nothing should hinder me from assisting ye cause. Butt since I’m ane invalide and cannot doe good, I shall indeaver to advise all young men to Joyn.

There were a number of different reasons why someone might join the Jacobite army in the late summer of 1745, just as things were starting to heat up after the arrival of Bonnie Prince Charlie in the Western Isles of Scotland. Specific motivations to pick up arms or to help others to do so were as disparate and multi-layered as the individuals involved in the conflict, as were their levels of sustained commitment as the campaign progressed.

Some fought for the ancient claim of the Stuart monarchs, and some stood in opposition to the parliamentary union that bound together England and Scotland into a single kingdom. Many resented being forced to accept the authority of the presbyteries over the traditional Divine Right of kings, especially when it came bundled with oaths of fealty to a sovereign from Lower Saxony. Others reckoned that they would be better off without the influence of a comparatively liberal representative government, an establishment which to them symbolized the decay of traditional values – especially in certain long-established and autonomous regions of ‘North Britain’.1

© 2026 Little Rebellions

Modified Hemingway theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑