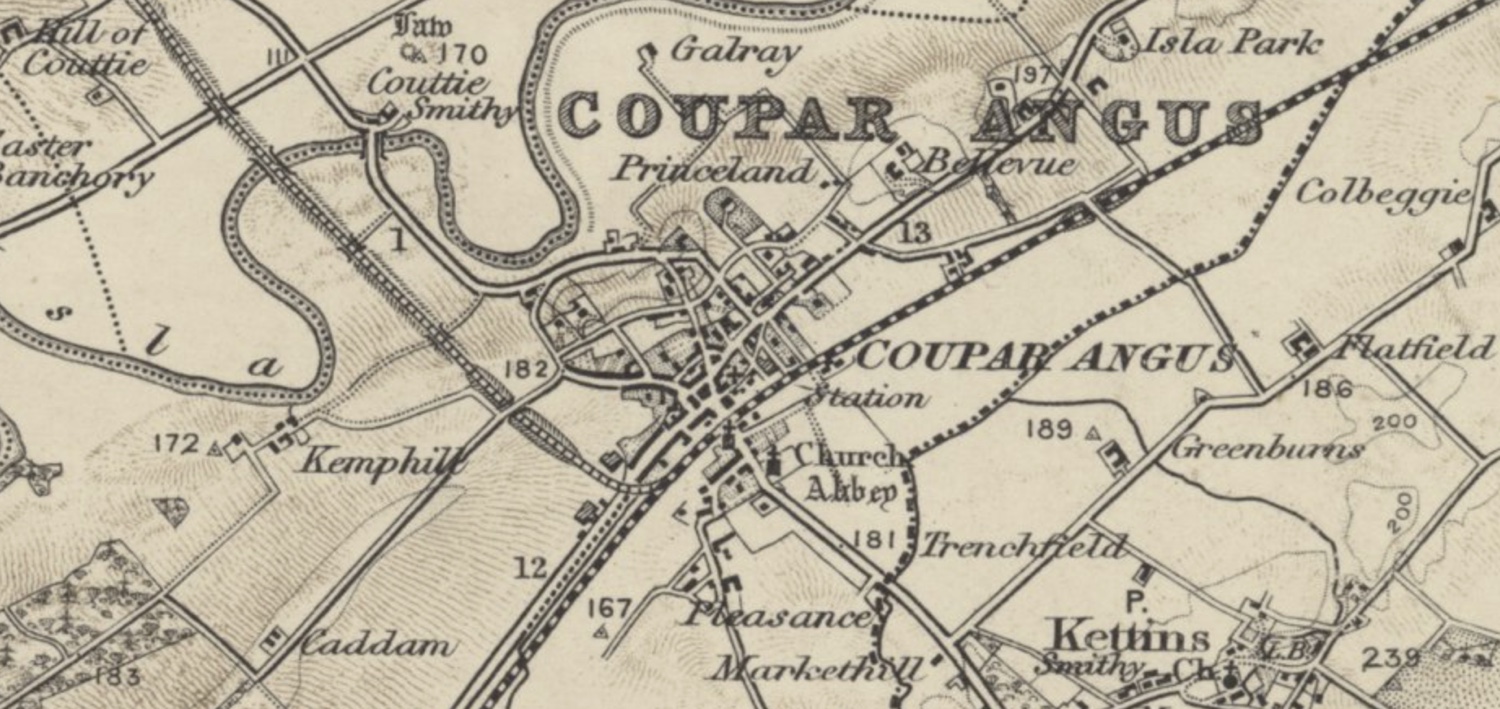

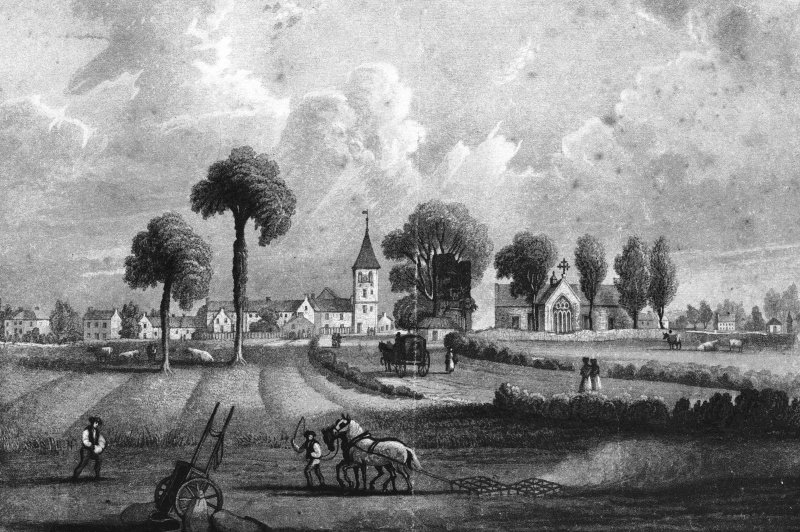

Like many small towns in the path of the rapidly coalescing Jacobite army, the autumn of 1745 was an eventful one for the inhabitants of Coupar Angus. The annual drudgery of the harvest was interrupted across various regions of Forfarshire and Perthshire as swelling companies of rebel soldiers made their ways southward toward Edinburgh. In late September and early October, inhabited towns and villages along the army’s route were solicited by Jacobite recruiting parties looking for warm bodies to join the cause. Requisition officers wrote up strict demands for civic officials to provide supplies for the benefit of the Bonnie Prince’s war effort, and Gàidhlig-speaking strangers in Highland clothing were billeted in private homes without regard for the owners’ approval. Few political conversations occurred openly, as one never knew who was listening in. Clandestine meetings and furtive confabulation concerning treasonous topics were not uncommon occurrences in Coupar Angus, nor in any locality where Jacobite designs were taking shape.

According to the accounts of several common citizens throughout the rural Scottish Lowlands, this harvest season brought with it a palpable frisson that many regarded with equal parts excitement, trepidation, and ambivalence. Though the last Jacobite rising quickly gained momentum in its opening weeks, many participants knew even at that bullish time that success for Forty-five was by no means a sure thing. Matters were especially complicated for those who wanted to remain neutral or otherwise avoid being involved in such a dangerous gambit. And despite the profound vein of Jacobite support that ran through a broad range of disparate Northern Britons, the overwhelming majority of Scotland’s population was firmly set against the idea of a return to Divine Right monarchy under the Stuart kings.1

What this meant for Charles Edward Stuart and his army of revolutionaries was that it was not such a simple thing to rely upon great swathes of willing supporters to fill the Jacobite ranks, especially when doing so required raising arms against an anxious government that had turned back a similar (though significantly larger) crisis only thirty years earlier. Certain measures were therefore implemented by the Jacobite leadership to maintain the composition and cohesion of the army, which necessarily impacted those who were reluctant to endorse it. In Coupar Angus, these measures deeply affected forty-seven-year-old legal writer Charles Hay, who also functioned as a deputy bailie for the regality of the town.

Bailie Hay was first notified of his role to play in the rising by Jacobite requisition officers on 12 October, when William Ker, James Rattray, and a man named Browne (likely Ignatious) transmitted numerous letters to him affirming their commands to secure transport supplies for the use of the army. These orders were explicitly stated to be carried out under severe punishment:

In The Name of his Royal Highness On pain of Corporal punishment, and being Made Prisoner by the Serjeant That Brings you this Order I Order you to have here in two hours time fourty Carts well Harnessed with good Horses, And three Riding Horses besides these already Furnished by the Village If You do not Instantly obey these Orders without loss of time, You Shall be Furthwith brought prisoner to Edr.2

Yet Hay evidently delayed in providing these supplies for at least two weeks, as the letters continued with an increasing quantity of demands. By 22 October, Rattray was calling for twenty-eight artillery horses, fourteen saddle horses for Jacobite officers, and billets for sixty men, all to be furnished ‘upon Your Perill’, threatening that if Hay did not act quickly or tried to run away, he would allow the Highlanders to pillage his home.3

It appears that eventually Hay was worn down and that soon he acted in accordance with the demands put upon him through the winter months of 1745, as Lord John Drummond was making his way southward from Montrose with hundreds of freshly landed troops in French service. Numerous residents of the area later testified that Hay functioned as a quarter master for the Jacobite army, confirming that he ordered the country people to give their horses and carts to the rebels. Some also provided accounts of Highland soldiers who invoked the bailie’s name when approaching locals for additional supplies and lodging. Furthermore, he was seen by many at the town’s mercat cross reading aloud the manifesto of Charles Edward Stuart – a crime that fit squarely in the category of treason to those who were loyal to the established government.

Despite the depositions of eight witnesses against Hay for his part in abetting the rebel soldiers, government justices neither imprisoned him nor otherwise detained him for trial. In fact, not only was Hay used to provide testimony against captured and suspected Jacobites in July 1746, when the crisis was well over, he also assisted the process of gathering evidence by conducting the official investigations in Coupar Angus.4 It is only after we compile and contrast over two dozen archival records from different collections relating to Bailie Hay that we are able to understand the full scope of his predicament.

Did Charles Hay help the Jacobite army by providing supplies and quarters for its soldiers? Absolutely he did. We know when this occurred and how some of the residents of Coupar Angus felt about it.5 For as many corroborations of his involvement as are recorded, however, there is a distinct undertone of trepidatious forbearance in the language of the testimony. Rumor had it that Hay was forced into his role, and though few actually saw evidence of this coercion, three of the eight depositions against him mention that this might have factored into his cooperation with the rebels.

Four further witnesses offered purely exculpatory proof on Hay’s behalf, including some dire reports that documented the severity of his position. The wright John Bell swore that he saw a party of Lord Ogilvy’s men drag the bailie out of his home to the mercat cross, where he publicly read the declaration of James VIII’s restoration to the throne of the Three Kingdoms. Bell related that Hay was surrounded by soldiers with their swords drawn on him, and that David Ogilvy of Inverwharatie swore ‘by God That he would thurst Mr Hay thorough with his Sword If he did not Speak Louder’. James Carver and James Geikie recalled that in the winter of 1745 an armed group of men went looking for the bailie so they could commandeer materiel for their southward march. The two witnesses claimed that Hay had attempted to hide himself, but the soldiers went ‘Stobbing through the Beds and Threatning to Destroy Mrs Hay & burn the house if her Husband was not found’. Certificates attesting to Hay’s loyalty were subsequently provided by the minister of Coupar Angus, James Spankie, suggesting that any help he gave to the rebels was offered only ‘to prevent the ruin of the town & Country’.6

These attestations painted a very different picture of Hay’s role in the rising, and collectively they proved to be of enough substance to exonerate him. Perthshire Deputy Sheriff George Miller, the man in charge of sorting out the guilty from the innocent in the region, wrote in his summary of Hay’s exculpatory evidence that due to ‘the Severe Threat of the Rebells and the Danger the Country was in from them he was obliged Sometimes to act much against his Inclination’.7 Despite the chaos in Coupar Angus as government officials tried to piece things together after the rising, the bailie had been vindicated: he had complied with the Jacobites in order to preserve the town.

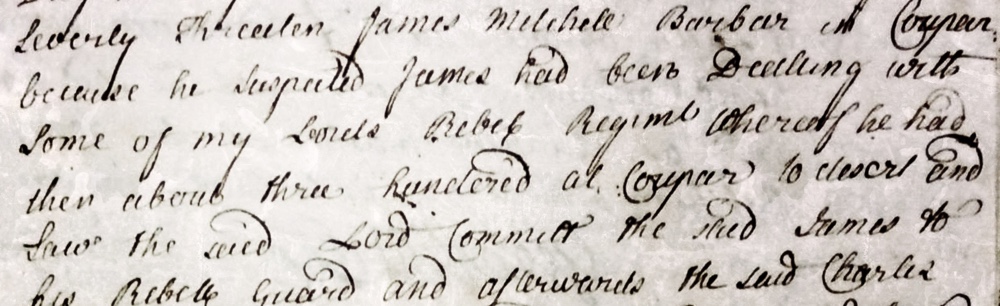

Vintner David Clark went one step further in attesting to Charles Hay’s good intentions. The winemaker had seen Lord Ogilvy himself threatening a barber in the town named James Mitchell for attempting to convince a contingent of three-hundred Jacobite soldiers in Airlie’s regiment to desert their posts and to go home. Ogilvy caught wind of this and imprisoned Mitchell immediately, which prompted Bailie Hay to negotiate for his release. In the end, it took a trade of six of the town’s halberds to secure the freedom of a man who had tried to mitigate the rising simply with some persuasive discourse.8

Conversely, Lord Ogilvy is portrayed by the citizens of Coupar Angus has having quite the vengeful streak. The earl of Airlie had entered David Clark’s home on the same day that Hay was compelled to read the Jacobite manifesto at the mercat cross. Upon seeing a poster on the wall that featured the signatures of a number of excise officers and the face of King George stamped upon it, Ogilvy pulled it down and tossed it out the window and into the street. Clark went on to depose that Lady Ogilvy, who had also occupied his house along with her husband, saw through the window a man named Thomas Eroch pick up the poster, at which point she called out for passers-by to ‘Beat the fellow hard’. Both Lord and Lady Ogilvy were seen by numerous townsfolk holding swords above the head of Charles Hay at the mercat cross.9

The value of presenting this scenario is self-evident: there are always (at least) two sides to every story. It is all too easy to rely upon established attitudes toward historical topics that neatly divide into good and bad, right and wrong, ‘loyal’ and ‘treasonous’. Human behavior is ultimately fueled by context and rarely can we accurately forecast how one would act when thrust into a dreadful situation with so much at stake. Bailie Charles Hay was thought to be both a rebel officer and an uncompromising bureaucrat, according to the accounts of his contemporaries. The reality, as we see by looking closely at a variety of records in the archives, was that he was both and he was neither. Indisputably, like many Britons affected by the Jacobite risings, Hay walked a fine line to ensure the preservation of the status quo and of his community.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and Open Access.

[…] was a fair bit of commotion upon the mercat cross of Coupar Angus one mid-October day in 1745. Bailie Charles Hay, a locally known clerk and town magistrate, stood at the nexus of George and High Streets with a […]