In last week’s post, we set out to introduce the value of a historical database by thinking critically about historiographical and biographical data related to the Forfarshire Jacobite regiment lead by David Ogilvy in 1745-6. While this may seem like a straightforward prerequisite, a comprehensive survey of both primary and secondary sources that address the constituency of this regiment presents a labyrinthine paper trail that requires us to carefully scrutinize the information heretofore recorded. Getting a firm grasp of this ‘lineage’ of data is essential to upholding the accuracy of what is finally entered into our database.

As we suggested last week, simply copying biographical information from published secondary- and tertiary-source name books or muster rolls is not enough to ensure that the data is accurate or even relevant. In short, this practice is ‘bad history’ and opens up the analysis to errors, inconsistencies, and others’ subjective interpretations of primary-source material. In the effort to combat this, we need a methodology that maintains the integrity of the original sources as much as possible while still allowing us to convert them into machine-readable (digital) format. Part 2 of this technical case study will demonstrate one possible method of doing this.

When we discuss the term ‘clean data’, we are referring to information that is transcribed into digital format with as little subjectivity as possible. This means misspellings and known errors from primary sources are left intact, conflicting evidence from disparate documents is retained, and essentially no liberties are taken by the modern historian or data entry specialist to interpret or otherwise blend or ‘smooth out’ information upon entry. Though it might seem unwieldy to use raw data with so many chaotic variables, it would be fundamentally distorting the results to do otherwise.1 As long as we take the time to set up an effective taxonomy for transcribing (now) and analyzing (later) our data, the results will be well worth the extra care.

In the example of Ogilvy’s regiment, we surveyed a number of sources that provide the names and some biographical data of those who were allegedly part of the unit. Some of these sources agree, some of them conflict, and more than one of them harbor glaring duplications, absences, or other errors. As secondary sources copy each other’s information through the historiography, the errors also get passed along.2 To root out some of these issues, we may start by simply comparing all of the entries in the secondary sources with what primary-source documents we have available. This lets us double-check earlier historians who have consulted with some of the same primary sources, as well as adding others into the mix that have not yet been included. The fact that our ‘publication’ is not actually printed means that we may continually add more information to the database as it becomes available, and our repository will therefore never be rendered obsolete for as long as it remains curated.

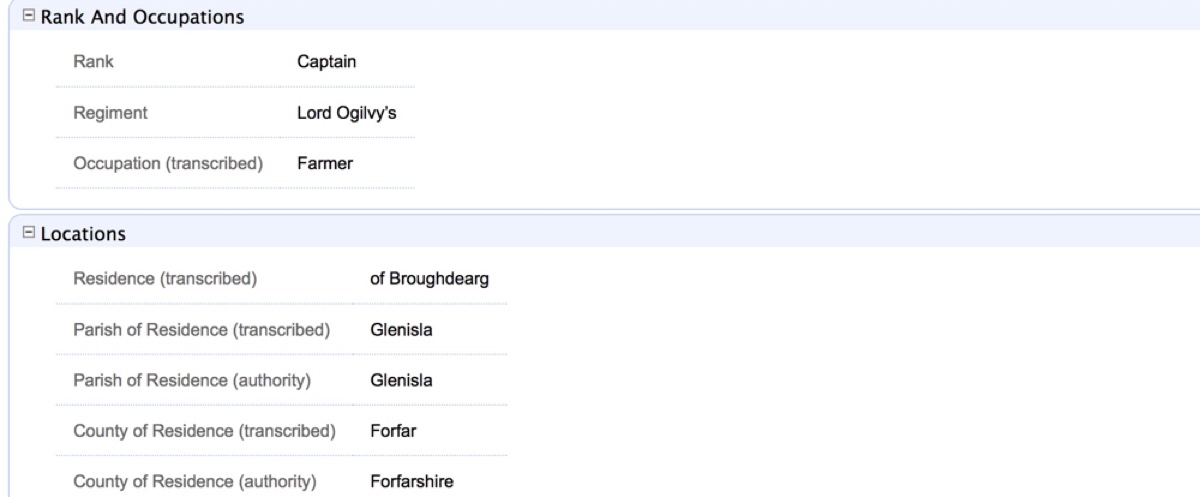

So everything, therefore, gets entered into our database: every name, every location, and every act of rebellion/defiance; every title, age, rank, and trial result.3 All of these entries are transcribed as faithfully as possible from the sources, whether they be primary or secondary, retaining misspellings and other misinformation so that we have an accurate representation of what the source itself records. This ‘clean data’ approach is what defines JDB1745 as an objective database: its curators are not altering the data to fit into a predesigned template, nor are we subjectively making decisions about what the original authors intended to write when errors, misspellings, and conflicts are discovered.

How could we possibly carry out effective searches if there are no standardized spellings or commonly acknowledged terms across the tables? We implement a system that libraries all over the world have been using for centuries: authority control. Establishing machine-readable authority records (MARC) allows us to create a unique ‘thesaurus’ for each attribute or field without altering the original data. This ensures that a search for Macdonalds will bring up all entries containing Macdomhnaills and Macdonells; a search for captains will include ‘captaine’ and ‘capt.’; and a search for shoemakers will return results that include cordwainers and brogmakers. The level of data inclusion put into authority records can be excruciatingly fine, and this presents itself most notably when grouping variants of person names and place-names, especially in Scotland, where the roots of many cultures and languages have left their marks upon the people and locations.

Authority records are indeed subjective, insofar as that determinations are made by the database curators which parcels of information should be related to which authorities. As the original data is also present in the fields that are brought up in a search, however, individual researchers may come to their own conclusions and analyses, and they will also find citations of the original sources for further scrutiny outwith the database environment. Authorities, therefore, are a tool for organization and classification rather than data analysis. It should also be mentioned that these authorities are cleanly structured and based upon standardized schemes for reference. Occupational authorities, for example, are based upon the Booth-Armstrong classification matrix, while onomastic authorities are compiled from data furnished by the Old and New Statistical Accounts of Scotland and the ever-helpful ScotlandsPlaces crowdsourced project, as well as a wide range of gazetteers and map resources.4

We now have some solid plans about how to think about and how to treat the ‘clean’ data that we will use for our assessment of Ogilvy’s regiment. Next week’s post, which will be the last in this particular series, will describe how we query and analyze this data to glean relevant demographic information about the Jacobite solders who marched within it. As an added benefit, this methodology will offer us the opportunity to test how each successive historiographical source has treated the information that they claim to report.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata organization, and Open Access.

[…] previous two posts, we introduced a case study model to demonstrate the utility of JDB1745 and we discussed a possible methodology that will give us more accurate results than what has hitherto been published. Now that we have […]