If you enjoy bewilderingly complex historiographies and you’re wondering exactly what is the purpose for the creation of a historical database like JDB1745, this post is for you. What follows is a use case involving a limited analysis of the Forfarshire Jacobite regiment under David Ogilvy, 6th Earl of Airlie, and how a tool like JDB1745 can help us collect and define detailed information across a number of disparate primary sources. This method of analysis, called prosopography, is essentially an intersection between historical sociology and data-based biography that has risen to prominence as our ability to collate and process big data has matured. By comparing and contrasting large amounts of discrete characteristics about historical personae, we can better understand the context of their lives and we can make more confident assertions about their roles and characteristics in the historical timeline.

Perhaps no more deserving of this disciplinary application is the ever-popular Jacobite era, which has long suffered from misinterpretation, mythistoire, and insufficient data. Though we are currently enjoying a popular resurgence of interest in the subject during the lead-up to the 275th anniversary of the Battle of Culloden, scholarly exploration of plebeian Jacobite demographics is extremely limited and many primary sources remain generally out of easy public reach.1 This, at its core, are the reasons that we created The Jacobite Database of 1745.

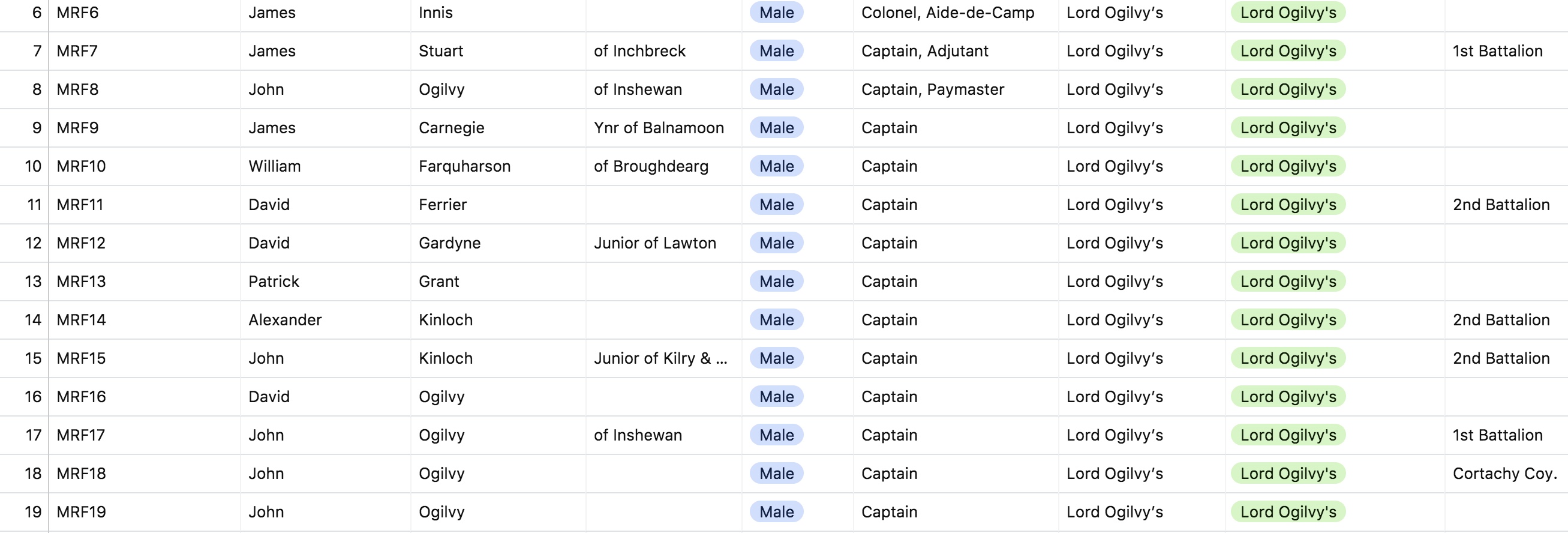

To demonstrate its value, we present a short step-by-step example of how the database can be used as a tool for data analysis that both professional and armchair historians alike will be able to use for their own research. We chose Lord Ogilvy’s regiment because it was significant through the entire Jacobite campaign of 1745-6 and is a unit for which we have a good number of distinct sources to turn to in the example. It is also the intention of this post to illustrate the importance of thinking about the lineage of data to keep it as raw (objective) as possible, as well as organizing it in a way that eases analysis rather than hinders it.

The best source with which to start is Alexander Mackintosh’s regimental muster roll from 1914, which gives us 630 persons to form the core of our personae data.2 Along with their names, Mackintosh provides (when known) title, rank, age, occupation, and residence, as well as some limited biographical information for a handful of the persons. In the introduction, he notes that this muster roll is compiled from a number of primary-source lists made up by the government’s excise officers, who were instructed to furnish each area of Scotland with the names of all who were thought to be involved in the rising.3 We must keep in mind, however, that not all of these names are definitively those of men who took up arms or even had Jacobite inclinations, but were rather those known or suspected to have done so. Not all were in Ogilvy’s (or any military regiment, for that matter) and not all were ever captured, tried, or punished. Some were even falsely accused or set up by personal enemies and are nonetheless included in these documents. In short, these were preliminary records that attempted to establish a baseline of opposition from which the government’s judicial officers could begin investigating.

Mackintosh likely also referenced Lord Rosebery’s earlier published roster of names (1890) from these selfsame lists which ostensibly provided a subjective transcription and interpretation of the documents used in his Forfarshire muster roll.4 Both Mackintosh and Rosebery freely admit, however, that their works are hardly complete or definitive. We know that at full strength, Lord Ogilvy’s regiment was probably at maximum around 900 men, so even if Mackintosh’s full 630 were all authentically part of that unit, there is still a considerable number of names missing.5 And still the waters get muddier in 1928 with the publication of the Scottish History Society’s three-volume study compiling all of the then-known Jacobite prisoners captured by government officials.6 Though Seton and Arnot use both Mackintosh and Rosebery as references, only 262 soldiers from Ogilvy’s regiment are identified in that compendium. Their goal was to focus directly on the prisoners rather than the full muster – including many noncombatants – so it makes sense that their numbers would be significantly lower than the total strength of the unit. Just to make things more complex, Henrietta and Alistair Tayler concurrently published a detailed study of Jacobite activity in the north-east of Scotland (a region from which many of Ogilvy’s men were recruited), wherein they take Rosebery to task for his mis-transcriptions and errors.7 Their contribution adds another 307 names from the most populously Jacobite region of Britain found within manuscripts in the Public Record Office (now TNA) and British Library, and concurrently demonstrates the evolving nature of our knowledge about the constituency of Jacobite support, as well as confirming the discovery of further sources that describe it.

And then we flash forward to 2001, when the latest edition of the 1745 Association’s Muster Roll was released, which records 751 names connected to the Forfarshire regiment.8 While this book is still used by many prominent scholars as the definitive list of military strength during the last Jacobite rising, the work is ultimately inaccurate and insufficient. This is not just due to the fact that the 5184 names it contains is less than one-half (and perhaps as little as one-third) of the total strength of the Jacobite army in 1745-6, but more so because it is a largely a sloppy compilation of other secondary sources with numerous duplications, inconsistencies, missing sources and references, and poor copy-editing.9 Yet the men of Lord Ogilvy’s featured in this muster roll can and should still be factored into the study for the sake of comparison, as long as the data is filtered or otherwise isolated from the other sources.

These hundreds of names shared between differing publications of divergent primary and secondary sources collectively present a real problem to the modern researcher. When seeking to understand the authentic demographic composition of this prominent Jacobite regiment, how can we efficiently and effectively collate all of the relevant data while ensuring that an objective analysis is undertaken? The answer to this and the steps that we will take to reach that solution are coming in next week’s post on Little Rebellions!

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata organization, and Open Access.

My 5th gr-grandfather was a Captain in Lord Ogiliy’s Forfarshire Regiment. His name was Patrick Wallace, from Arbroath.

Captured after Culloden and imprisoned in the Tower of London (where my 4th gr-grandmother was born).

[…] our previous two posts, we introduced a case study model to demonstrate the utility of JDB1745 and we discussed a possible methodology that will give us […]

[…] of them within their three-volume compilation of Jacobite captives.4 As we have demonstrated in our case study of Lord Ogilvy’s regiment, following the lineage of biographical data back to the primary sources is essential if accurate […]

[…] reinforce our recent discussion of critical thinking about the historical data used within a project like JDB1745, this […]

I would like to know more about detail the Ogilvy Regiments movements at Cuil Lodair….and get a list of officers and men from Deeside and Glenisla and Glenshee with the last name Of Shaw

[…] as well as its context. Following and challenging that data lineage is something about which I have repeatedly written, and this pursuit represents a significant role in the methodology of my everyday work, as […]