Of the many archival sources relating to the last Jacobite rising that still survive, one category of documents that is noticeably thin is that of personal letters from rebel soldiers. This makes sense for a number of reasons. For one, the army led by Charles Edward Stuart was almost constantly on the march during its eight-month campaign in Britain, leaving little time to write to family back home. Literacy among the rank-and-file troops was not particularly pronounced, and this is borne out by the number of Jacobite prisoners who claimed they could not write, instead leaving ‘their mark’ on government documents in place of a signature. Postal service through the Royal Mail and by private couriers was indeed active during the crisis, but was notoriously unreliable due to poorly maintained roads through often difficult and remote terrain, as well as the fact that the kingdoms were in the midst of a civil war. Packets of sealed letters were regularly seized by agents on both sides of the conflict and were broken open in the search for seditious material and intelligence within.1 As a result, thousands of missives never made it to their final destinations.

The signature marks of numerous illiterate Jacobite prisoners and witnesses against them

This dearth of important evidence means that it can be a bit more difficult to study the context of the common people who were caught up in the rising, both within the Jacobite army and on the home front. Newspapers and magazines of the time were valuable for getting out basic (and sometimes pointed) information to the masses, but they are nowhere as intimate or revealing as the personal letters themselves. Thankfully, a few significant collections of these letters written by plebeian soldiers and their family members are still preserved in various archives, and they shed a fascinating light on what it was like for some of the ‘ordinary’ people in Britain who were involved – willingly or not – in Jacobite designs during such a tumultuous period.

One of these collections lies within the Secretary of State Papers, Scotland at the National Archives in Kew, a packet of intercepted post that was found on the person of James Grant, a carpenter from Fort Augustus who was employed by the Jacobite army to carry their communications. Grant was captured by General Guest sometime in early November 1745 with the parcel and some money, though he told the authorities that he was working for both camps and also served as a courier for the government.2 Collectively, the sixty-one letters taken from this man represent a remarkable snapshot of life within the Jacobite army in the weeks following the Battle of Prestonpans, after the decision was made to cross the border into England but just before it was enacted.

The letters themselves were mostly written between late October and early November 1745 while the army was encamped on the outskirts of Edinburgh at Musselburgh and Dalkeith, and just after it marched southward to Moffat. Many are from the hands of regular soldiers, with around 40% written by officers of the ranks of lieutenant or higher. The contents are quite a mixed bag, containing everything from local intelligence reports to recruitment demands to instructions for managing the affairs of individual farms while its masters were away. These are accompanied by some particularly heartfelt personal letters written to loved ones back home, or messages from wives and siblings hoping to reach their soldiers before the army crossed into England.

A few specific turns of phrase are powerfully visceral, with some conveying an air of trepidatious confidence about the army’s chances across the border and others pledging passionate feelings to spouses and family whom they might never see again. Excited rumors of aid from France in the form of thousands of men and shiploads of arms and ammunition punctuate some of the prose, but this hopefulness is contrasted by reports from officers who repeatedly call out difficulties in recruiting and the incessant desertion amongst the ranks of common soldiers. Lord Ogilvy himself writes to Lieutenant-Colonel Sir James Kinloch on 7 November complaining that starvation was causing ‘considerable’ desertion which lost him ‘a good many’. He underscores this issue by reminding Kinloch to post ‘a trusty rear Guard’ to prevent the men from melting away while on the march. Ogilvy also gives orders to investigate monetary theft and to bring men along as prisoners if they try to make excuses for their absence.3

Within the personal letters, in between sentiments of longing and anticipation of coming home after the completion of their martial duties, are directions about the maintenance of daily affairs on the home front. Detailed vignettes of agrarian toil and estate management are illustrated by references to a variety of jobs, many of which would only get done with the competence of the women who were left at home. These responsibilities included small tasks like the selling of a neighbor’s cow or hiring servants for labor-intensive projects in the fields, but wives were also charged with handling financial affairs and other estate business in their spouse’s absence.4 Collectively these fragments offer compelling evidence of the vital role played by plebeian women whose lives were also directly affected by the Jacobite affair.

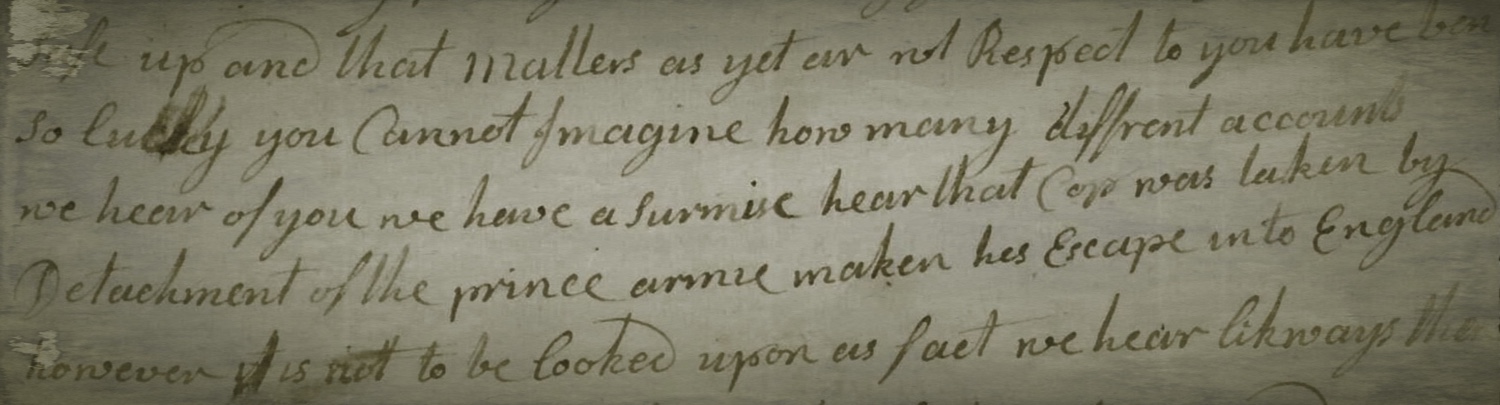

One letter in particular is especially noteworthy because of its vivid immediacy and candor; in fact, within extant documents from the Forty-five it could be considered unmatched in describing the civilian experience of war through the ache and confusion of separation.5 The writer is Ms Anne Abernethy, wife of Robert Forbes of Corse in Strathbogie. Her missive is dated 21 October and was sent from the town of Huntly in Aberdeenshire to Edinburgh via the care of a writer (an attorney or notary) named Ruddoch. Forbes was then on the march with the Jacobite army and headed for England, and Abernethy had been informed by the servant of another soldier who had returned to Aberdeenshire that her husband had been seen in good health. She gently expresses her disappointment at not hearing from him directly, but quickly turns her attention to conveying the many rumors swirling around the country and her earnest wishes for his safe return. It is a remarkably bittersweet message.

To Robert Forbes of Corse, Esquire

To the Care of Mr Ruddoch, Writer in EdinburghHuntly 21 October, 1745

My Dearest,

I take this opportunity of Mr Leith’s Servant who tells me he saw you well the day he left Edinburgh. I was surprised you did not write me, at is seems you knew of his coming to this country, but I must own I have no reason to complain of your negligence that way. I was glad to hear by your last of your getting safe up, and that matters as yet are, with respect to you, have been so lucky. You cannot imagine how many different accounts we hear of you. We have a surmise here that Cope was taken by a detachment of the Prince’s army while making his escape into England, however it is not to be looked upon as fact. We hear likewise there is to be a fight before you leave Edinburgh. If it be so I pray God may take care of you, and I’ll trust in Him who only can support me and every one under their trials. I hope a short time will determine your affairs now. I will be glad to hear if my brother Willam has joined the army or not. Your mother and sister offer their best respects to you.

In haste I am, my Dearest Life, yours till Death.

Anne Abernethie

We know quite a bit about Robert Forbes thanks to a significant collection of records relating to his imprisonment and trial, including his short military career with the Jacobite army. Forbes was a captain in Gordon of Glenbucket’s regiment, and was originally recruited by a party under James Moir of Stoneywood. Moir, of course, was the right-hand man of Lord Lewis Gordon, who served as the Lord Lieutenant of Aberdeenshire and was responsible for some of the most successful and draconian recruiting in the north-east of Scotland during the rising. Forbes, like many, did not enter willingly into Jacobite service, but nonetheless he was made responsible for arming and paying some of the soldiers during the march from Edinburgh to Derby and back to Carlisle after their retreat. According to precognition briefs and transcripts from his trial, thirteen witnesses at London and thirty-five at Perth saw him fulfilling his duties as an officer while the Jacobite army was in Carlisle, but a vigorous defense was presented that weakened the prosecution’s case against him.6

Nine witnesses for the defense were able to convince the judges that Forbes was targeted by Jacobite recruiters for giving supplies and volunteers to Sir John Cope before the Battle of Prestonpans. Three of them testified that a recruiting party of twenty Jacobite soldiers carried him away while he was in his own home, ‘fetched in sleep, dragged out bareheaded and coat torn’, and said that Forbes had offered the soldiers money and his worldly possessions if they would only let him be. One witness later saw Forbes in custody while in Dundee before the army had made its way to Edinburgh in September 1745, and yet another swore that Forbes tried to pay a customs inspector in Leith to take him across the Forth to freedom while encamped in the capital. And though he was seen by dozens of people working for the Jacobite army at Carlisle, two locals claimed to have helped Forbes don women’s clothes in a failed attempt to escape the town – decidedly similar to the scheme used by Charles Edward Stuart during his flight from Scotland at the end of the rising.7

All of this evidence and more was sufficient to exonerate Robert Forbes and he was acquitted after a three-hour trial on 24 October 1746. In all, he had spent nearly ten months imprisoned at Carlisle and at Newgate and Clerkenwell in London, and it had been over a year since he had been home with his wife Anne. This casts a rather dismal light on her captured letter, wherein she was cautiously optimistic about his safety and luck at that particular time. Reviewing her language and tone, there is no obvious resentment or outrage at her husband literally having been kidnapped into the rising, which raises questions of how those involved might have defined concepts of duty and compulsion. The scenario also suggests that Jacobite recruiters took serious umbrage at those who abstained from joining the cause and especially those who gave assistance to government forces. Notably, if the witnesses can be believed, it actively fueled their intent to bring this particular target into the ranks. Indeed, this was a tactic used regularly by Jacobite press gangs.8

We know that Forbes tried on numerous occasions to desert his post, despite the responsibilities given to him by his superiors in the Jacobite army – which he certainly carried out, at least for a time. Acknowledging that the use of force was a significant factor in drawing rebel recruits, Hanoverian officials cited the weight of this evidence as enough cause for dismissal, declaring it ‘for the Honour of the Crown’ to make it so. Anne Abernethy would have her husband back after a year of anxiety and anticipation, sentiments indelibly recorded by her hand in an intimate captured letter that was never read by its addressee.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and Open Access.

Lovely post – I hadn’t thought about the fact that so few letters have survived. From my limited knowledge much of the evidence produced at trials was to prove that individuals had been ‘there’ so letters would have been significant. Maybe it does show the degree of illiteracy – or maybe there are loads of letters waiting to be discovered! My favourite letter is from Robertson of Faskally to his ‘Dear Mother’. hoping she will severely punish ‘our friends’ who had deserted ‘as it shows they had little regard to me to leave me at such a time’. A great… Read more »

Thanks very much for your comments, Mark. I have never seen the use of personal letters to prove the involvement of a suspected person at trial, but it sure makes sense that they could serve as strong evidence to indict – a very sharp observation! Yes, the Faskally letter is powerful; in the same bundle as the letter above are a few missives written by the ‘inferiors’ that show a great deal of respect and admiration for their feudal/contracted elites. Some in the north-east joined up specifically to please their hereditary landlords.

Thanks Darren, I haven’t seen these so will have to get up to Kew and have a look. Thanks for the information.

I am pleased to have found this site. My great grand aunt Mary Cameron had family letters written from the hulks of ships that held the Jacobite prisoners following Culloden. One of which was said to be written in blood. But she threw them out saying they “represented terrible times”.

Many thanks for reading along, John, and for sharing the anecdote about your family’s letters. What a regrettable loss of what sounds like some incredible sources!