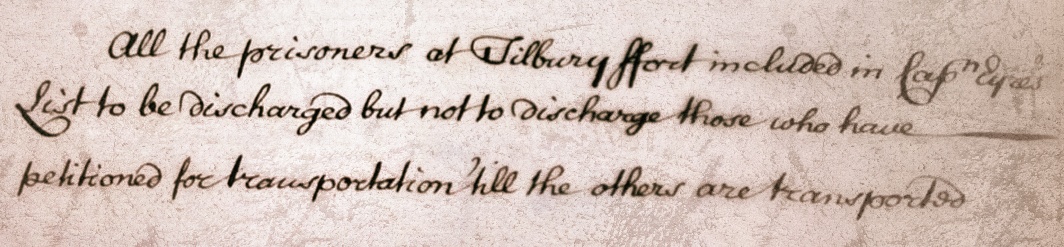

To-do lists are not only productivity tools for busy modern lives. They were also used extensively by eighteenth-century British government officials to keep pressing topics close in mind, and some even fashioned their memoranda as checklists to ensure they did not miss anything especially important. We see this practice in a document from the British National archives, where Sir John Sharpe, Solicitor to the Treasury during the Jacobite prosecutions after the Forty-five, lists a number of tasks to complete in the winter of 1746-7.1 It is a particularly interesting archival document because it gives us some idea of what critical topics of conversation concerning the prosecution of Jacobites kept government officials occupied. The fact that this task list was written nine months after the Battle of Culloden demonstrates just how much judicial red tape still existed well after the last rising itself had burned out.

Paraphrasing Sharpe’s list of to-dos, we may look in on numerous important points of policy as well as how Jacobite prisoners under charges of treason were processed and treated:

Item #1

Considering the method of how to send prisoners-of-war in French service back to France.

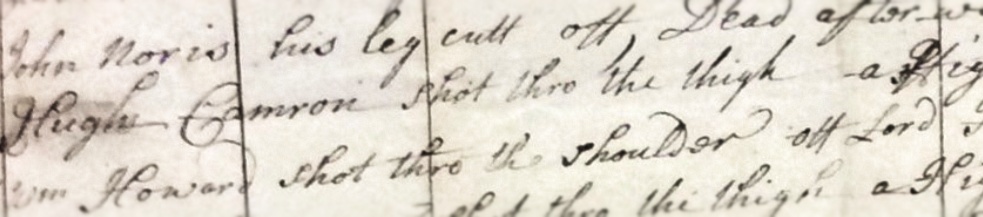

Sharpe notes that he needed to speak at length with Sir Everard Fawkener, the Duke of Cumberland’s secretary, about a peculiar issue: just how to discern which of the prisoners-of-war were really from France, and which were actually born within the Three Kingdoms. This was an important distinction because both the rights and the treatment of prisoners facing charges of treason were different depending on whether they were ‘subjects of the crown’ or legitimate foreigners under the protection of Louis XV. Perhaps unsurprisingly, more than a few of the captured Scottish and Irish soldiers in French service feigned foreign provenance in hopes that it might secure them a lighter sentence – or even freedom altogether. After the recapture of Carlisle by the British army, for example, a Jacobite adjutant in Lord Kilmarnock’s cavalry troop masqueraded as a French officer until a corporal from Hamilton’s Dragoons revealed him to be an Irishman with whom he had already been familiar.2 The Lord Justice Clerk Andrew Fletcher, however, saw no difference between those born in Britain or beyond, stating that anyone should be answerable to charges of high treason if they ever ‘had Residence in the King’s Dominions before the Rebellion’.3