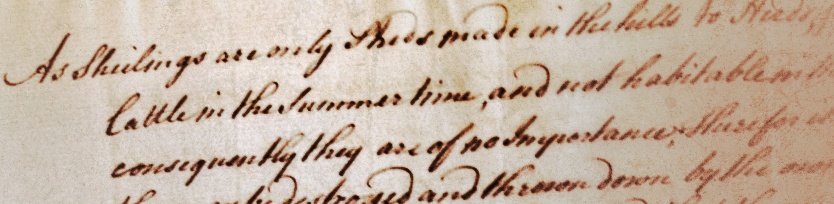

As Sheilings are only Sheds made in the hills to Herds, for herding Cattle in the Summer time, and not habitable in the Winter; consequently they are of no Importance; therefor it is required they may be destroyed and thrown down by the owners, so as they be no shelter to the Rebels; and that the owners may not plead Ignorance thereafter, and what ever houses have been burnt and destroyed are not to be rebuilt, without a Sign’d Order from the General or Commander in Chief. 1

Within the extensive annals of the Montrose Muniments at the NRS are three bundles of extremely interesting letters and lists that collectively provide a visceral, microcosmic snapshot of the last Jacobite rising in Scotland. After seeking permission directly from the standing duke of Montrose, for the past seven years I’ve been taken with transcribing the contents for inclusion within the database. During that time, the content has also provided some poignant content for my doctoral thesis, numerous lectures, and a forthcoming journal article.

Much of what is contained within these bundles highlights the uncomfortable predicament in which the then 2nd duke found himself: trying to maintain and defend the lives and homes of his contracted tenants – whether Jacobite or not – while upholding his duties and loyalties to the Georgian government of Britain, even through its heavy-handed tactics of rebel-purging after Culloden. In addition to some extremely tense back-and-forth correspondence between Montrose’s estate of Buchanan and the British military authorities based in Fort Augustus, the collection also contains lists of suspected rebels, declarations both for and against accused persons, and records of depredations carried out by King George’s troops throughout Montrose’s lands in the summer of 1746.

It appears that Montrose did his very best to walk the line of supporting his tenants while at the same time visibly proving his due diligence by carrying out the often pitiless regimens of ‘civilising’ insisted upon by the government. It is an understatement to say that the two goals were mutually exclusive. He kept closely in touch with his factors, most notably Mungo Grahame of Gorthie, ensuring that the instructions passed down by government officials were enacted to catalogue every parcel of land rented out and to assess the behavior and accountability of each soul under his jurisdiction. If thought innocent, tenants were to remain at home and to stay clear of any possible activity that would mark them as putative criminals in the critical eye of the government. If known to be in collusion with the enemy, they were to turn in their arms and submit themselves immediately to local magistrates. Montrose was pressed, being compelled to carefully monitor and inventory his entire estate in this manner, alternately condemning or fervidly attempting to exonerate the men and women subsisting on his land. It didn’t help that many of the historically notorious MacGregors held tacks and farms under the duke.

While the authorities in Fort Augustus and Stirling gave Montrose a modicum of the respect that he was due as a Peer of Scotland, they also made it glaringly apparent that he was oft regarded as just another shifty enabler who was likely harboring state criminals guilty of the most odious charges of high treason. As evidenced within its correspondence with Montrose and Gorthie, the government proved that it would much rather play it safe, indicting any moderately questionable person while ordering the removal of any possible hiding place in which a rebel might sequester.

The attached snippet of a copy order from General Bland was likely one of many that went out to lairds and factors in obstreperous areas of the country, to be read in public by local ministers at their Sunday services. In this one, Bland makes no bones about eliminating places to hide for those not inclined to the government’s authority. Any shelter still standing in the winter must be destroyed, and any new builds must be directly authorized by Bland himself or by a direct subsidiary. The owners of the land are expected to take an active role in ensuring this is carried out upon pain of intervention from the army. The order goes on to explain that if anyone is found harboring or selling foodstuffs or supplies to suspected or accused rebels, those persons will certainly have their belongings seized and their homes and property burned to the ground. A scorched-earth policy to maintain order if there ever was one. This is the very heart of civil war.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata organization, and Open Access.