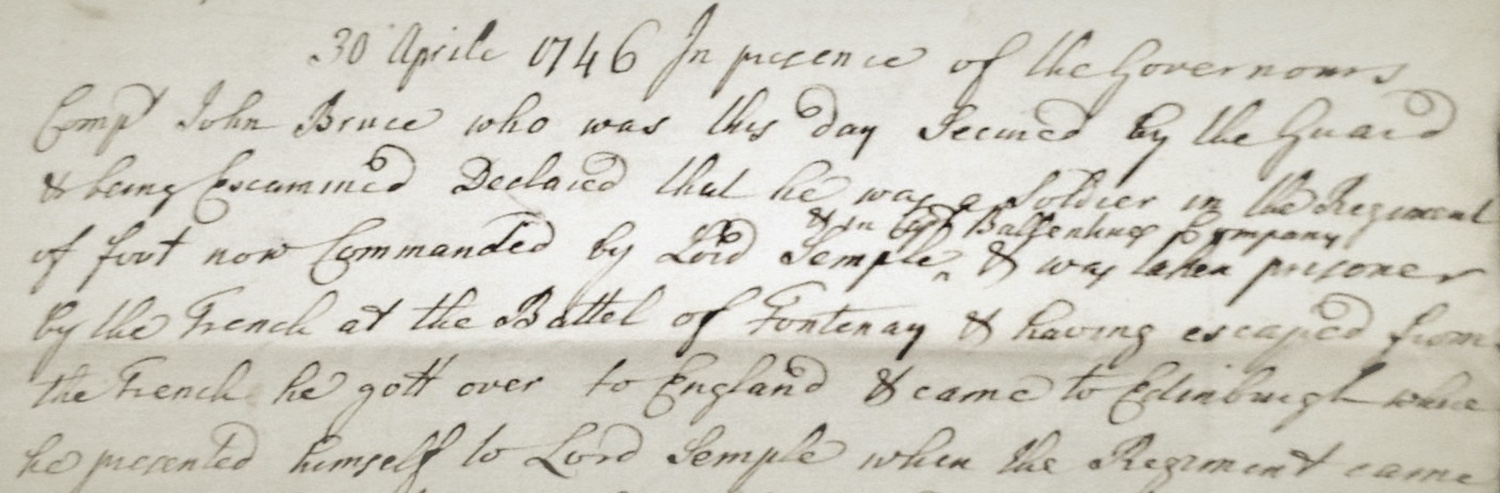

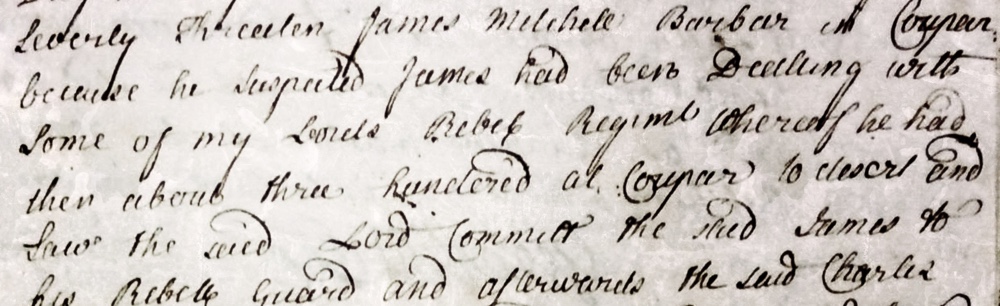

Deceptions and mistruths in eighteenth century judicial cases are rarely different from those in the modern day. The indicted have always lied to save their own skins or to provide cover for people and institutions they wish to protect. Though overloaded with prisoners and casework by the end of the last Jacobite rising, the British justice system was fundamentally sound enough to make the necessary adjustments to expedite an effective method of processing that massive influx of suspected persons. Many of those lessons were learned in the aftermath of the Fifteen, wherein the first Georgian administration sought to balance victory and clemency, hoping to establish an indelible hallmark upon the nascent regime.1 Thirty years later, the system was much the same, and though the categories of punishment scaled with an increased number of prisoners taken from a significantly smaller number of total participants, a fair and accurate penal process was again pursued by many of the Hanoverian ministers who were in charge of prosecution.2

A handful of high-profile Jacobite trials have since been published, offering readers a glimpse into the legal mechanics of treason cases against the Crown, but these are especially focused on prominent characters who were singled out to be made examples of.3 The best way to learn more about the regular folks who were involved in the last Jacobite rising is to go through the plethora of original documents housed in archives across Scotland and England, and sometimes further afield. The paper trails of these individuals are often fragmented on account of them facing examinations in the different places they were held, and subsequent prison transfers and other movements can sometimes make tracking them quite difficult. Nonetheless, the raw information left behind by the accused and by the witnesses in favor of or against them can shed valuable light on both the large and small events of 1745-6. It is worth the time spent piecing together these archive-driven stories, which is a focal objective of the JDB project.