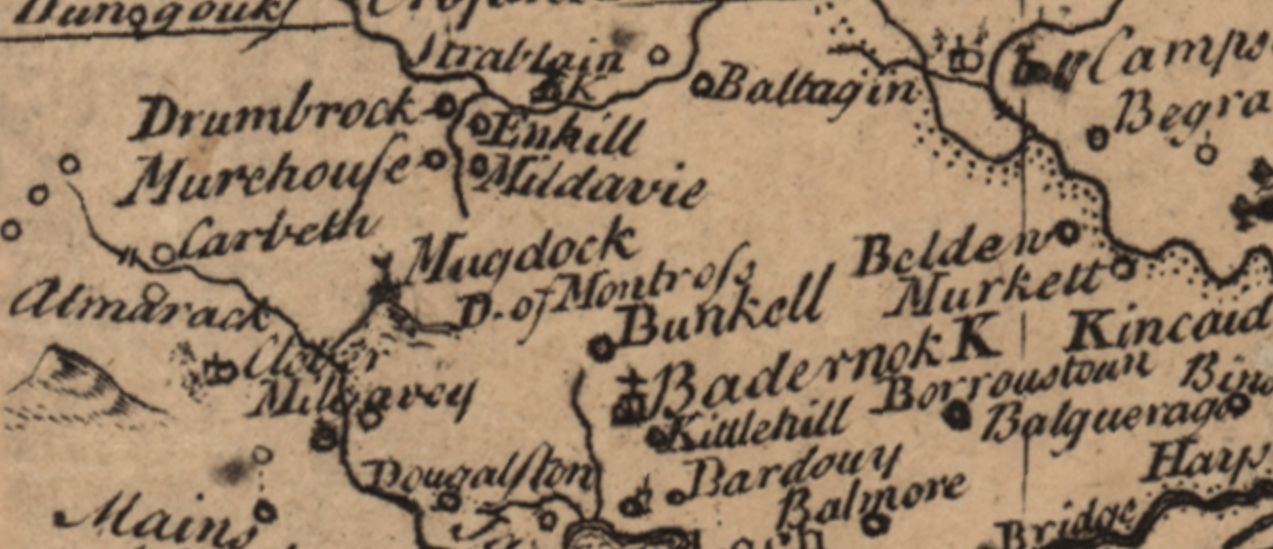

Sometime during or shortly after the Jacobite conflict in 1745-6, a tacksman of the 2nd Duke of Montrose named George Murdoch penned a troubled memorial to his laird. Within this missive, he explains that it would be impossible this year to honor his contract of tenancy, wherein Murdoch was to provide 8000 merks over a period of seven years as rent, capitalized by the cutting and sale of timber from Mugdock Wood in the Stirlingshire parish of Strathblane.1 The problem, he cites, is that the normal operations of business had essentially ground to a standstill on account of disruptive Jacobite activity in the region.

Murdoch’s contract, which had been worked up by Montrose’s factors in February 1744, contained the usual ‘salvo’ or contingency for disasters that might impede the regular course of trade. These included cases of war, pestilence, or famine – the most common uncontrollable misfortunes that could affect the timely payment of rent. The ‘publick calamity’ occasioned by the presence of Jacobite recruiters and soldiers on the loyalist estate of Montrose should be counted among these, claims Murdoch, and he asks for ‘prorogation’ or extension of the contracted time to exclude this unfortunate period of stale business:

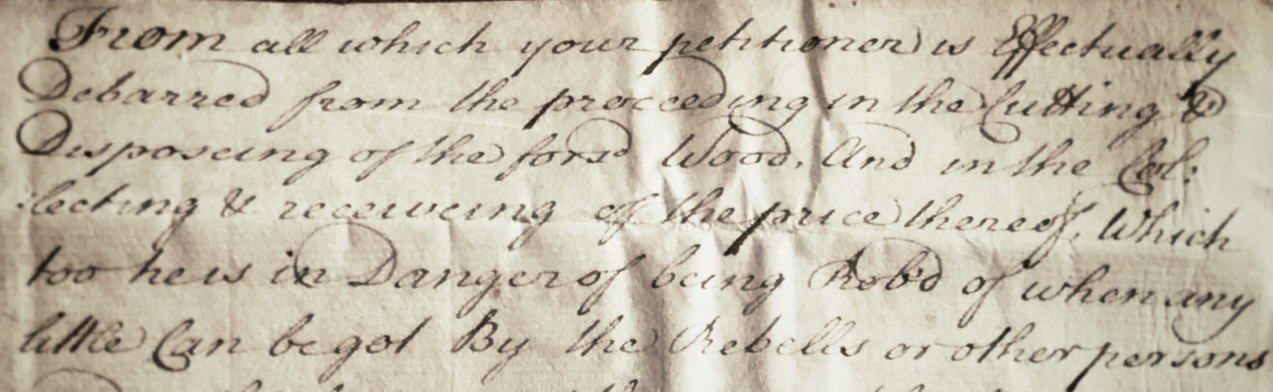

And now That by the present Insurrection & Rebellion in the Land a stop is put to all Business and very little progress can be made in Cutting & selling of the forsd wood And What is sold must be sold at an undervalue, and Cannot be got in as all payments are stopt by the stop thats put to all Courts of Justice in the Land, And that at present We are also threatened with Dearth From all which your petitioner is Effectually Debarred from proceeding in the Cutting & Disposeing of the forsd Wood, And in the Collecting & receiveing of the price thereof, Which too he is Danger of being Rob’d of when any little Can be got By the Rebells or other persons under the favour of the present Confusion.2

Murdoch’s predicament was not an isolated one. The last Jacobite rising might have been launched to restore the House of Stuart back upon the throne of the Three Kingdoms, but the consternation that resulted was felt well outside of the political realm, greatly impacting the financial comfort of the Scottish nation across the economic spectrum. From laborers to tacksmen, from landed elites to corporations and countless individual businesses alike, the complaints were thoroughly recorded throughout the conflict and for years afterward.

George Murdoch’s landlords in Stirlingshire had been feeling the economic downturn for months, describing to the Court of Session the ‘miserable situation’ in the area during the summer of 1746. Thanks to the ravages of the Jacobite-leaning Macgregors on the Montrose estate, noted Nicol Graham of Gartmore, the local inhabitants were ‘greatly discouraged from all manner of Industry and Labour, by reason of the precariousness of their Property’.3 Farther north in Inverness-shire at the outset of the rising, Lord President Duncan Forbes of Culloden petitioned the Marquess of Tweeddale for money to defend the town, describing that bank notes were devalued, stores of coin were locked up, ‘trade is at a stand and no one will part with the little money he is possessed of’.4

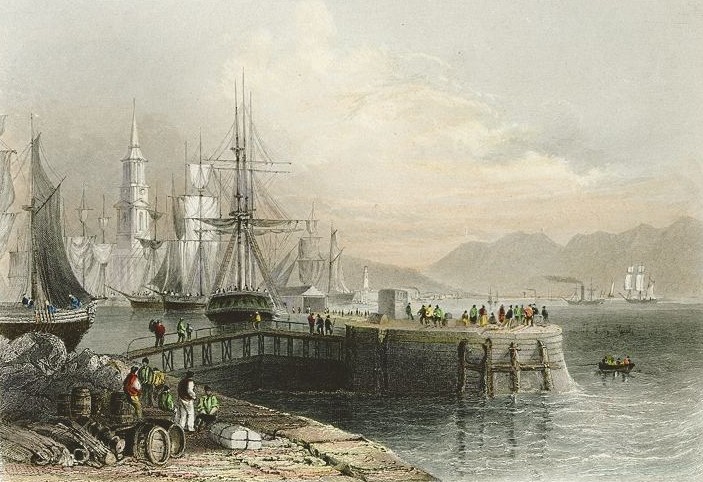

As early as the autumn of 1745, Glasgow provost Andrew Cochrane mourned the ‘absolute interruption of business’ in an otherwise burgeoning and vital port at the very peak of the tobacco trade. Customs-houses were locked down and even the suggestion of a rebel invasion was enough to economically hold the burgh hostage. Restrictions on the passage of goods-laden ships into British harbors were imposed by government officials and perishable commodities lay rotting in holds and upon docks not only in Glasgow but also in Aberdeen, Berwick, and Eyemouth.5

From Aberdeen to Edinburgh, the threat of occupation and civic uncertainty precipitated by the Jacobite rising deeply affected the normal course of business and instigated fear of a financial crisis alongside a political one. Much has been made of the social effects of this civil war, with Jacobite recruitment parties using increasingly draconian tactics to entice people into the army, genocidal retribution by government troops merely for suspicion of involvement with the rebellion, and families being torn apart by divided loyalties. But the pecuniary cost has yet to be tallied or even studied in depth, despite plenty of evidence still remaining.6

Ironically, Stuart declarations explicitly promised to relieve the financial burdens of ‘poverty and decay of trade’ by eliminating inequitable taxes foisted upon North Britain by its southern neighbor.7 Yet the simple recruitment of significant numbers of tenant-farmers into armies and militias on both sides of the conflict resulted in rents going unpaid and crops lying untended.8 Add to this the raising of ‘public monies’ by Jacobite cess-collectors, usually in the form of land tax proportional to a town’s standard rents ‘for his Highness’s use’, as well as mass requisitions for goods under threat of military execution, the Jacobite expedition brought great strain upon the very communities from which the movement hoped to draw support.9 Some towns and estates begged the government for reimbursement of these expenses after the rising was over, but few of them were granted.10

The memorial of George Murdoch is a small but sobering reminder that the reverberations created by the last Jacobite attempt were felt in all sectors of British society whether or not individuals were directly involved within the rising. It is also an allusion to the economic suffering of loyalist or even neutral parties who often are overlooked in favor of the well-documented physical suffering of Jacobite-connected communities in the months and years after Culloden. The implications of regime change, as well as the threat of occupation or the seizure of power – whether for a righteous cause or a treasonous one – have always created instability in the markets and within the very structure of a nation’s financial systems. Whether a Stuart restoration would have or could have quieted such sweeping concern and stabilized or even revitalized the ailing economy that its policies and actions exacerbated is indeed another matter.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and Open Access.

Really interesting post that gives a very different perspective – and has got me thinking about the Jacobite ‘occupation’. There is some evidence from Atholl sources – Thomas Bisset (admittedly not an unbiased witness) wrote ‘We have great resone to be wearied of our present arbitrary and military government in this country, and to prize and value our libertys when recovered more than ever we have. No mercats, no trade, all business at a stand, no administration of Justice, no traveling of the highway, except such as are in the Jacobit Interest and who have their passes, robery and oppressione… Read more »

Thanks for your comment, Mark, and also for the great Bisset quote, which is spot-on. We see this kind of language in all parts of Scotland during the rising. While it’s not surprising that things become disrupted during a time of civil war, there are some interesting conceptual truths that emerge when measuring the ‘benevolence’ of a movement predicated on restoring wealth and comfort to the people of Scotland. In other words, it’s useful to consider exactly whom a successful dynastic swap would have impacted, and in what ways.

Yes – and I’m sure you are right to suggest we should not bracket ‘benevolence’ with ‘Jacobite’ (I’ve just noticed how close the former word is to ‘violence’). However, I’m not sure you can equate how the Jacobite elite behaved during ‘the occupation’- when they were fighting for their lives – with how they might have behaved had they successfully seized power? I still question whether the plebeians in the Jacobite army could have behaved with such bravery/achieved so much in 1745/6 unless they were strongly motivated to be there. I must say though that I like Bisset’s words which… Read more »