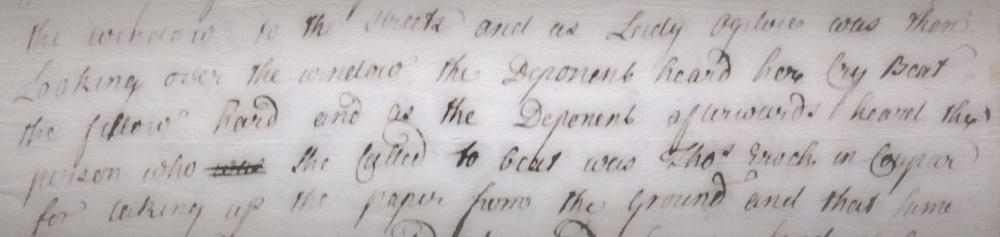

There was a fair bit of commotion upon the mercat cross of Coupar Angus one mid-October day in 1745. Bailie Charles Hay, a locally known clerk and town magistrate, stood at the nexus of George and High Streets with a copy of Charles Edward Stuart’s manifesto and read it aloud to a rapidly assembling crowd. This was an overtly treasonous act by a man widely thought to have been loyal to the British government of George II. But as the ruckus played out, witnesses would allegedly see a number of prominent Jacobite personalities join Hay on the cross and physically compel him to address the busy town centre on behalf of the exiled Stuarts.

According to some of the townspeople who were present, the Lord of Airlie himself, David Ogilvy, stood beside Hay with a sword in his hand, making certain that the bailie got it right and explicitly proclaimed James VIII & III as the rightful ruler of the three kingdoms of Britain. Also there on the cross were two sons of Sir John Ogilvy of Inverquharity, Thomas Ogilvy of East Miln, Charles Rattray of Dunoon, and Airlie’s wife, Margaret Ogilvy. All of them, including Lady Ogilvy, were alleged to have had their swords drawn and either pointed at Hay or held above his head as he hoarsely read out the terms of the Jacobite occupation.1