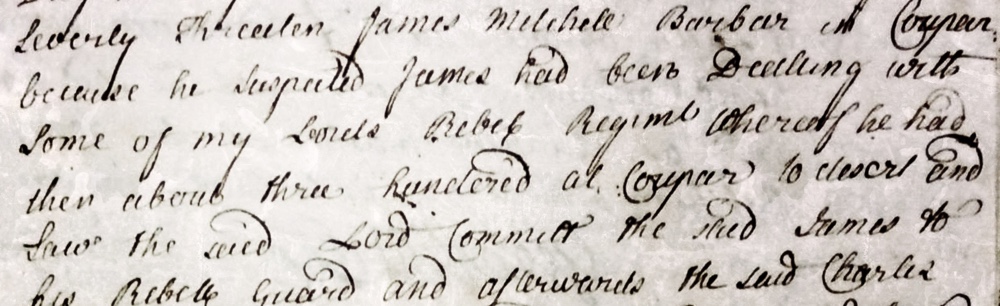

Like many small towns in the path of the rapidly coalescing Jacobite army, the autumn of 1745 was an eventful one for the inhabitants of Coupar Angus. The annual drudgery of the harvest was interrupted across various regions of Forfarshire and Perthshire as swelling companies of rebel soldiers made their ways southward toward Edinburgh. In late September and early October, inhabited towns and villages along the army’s route were solicited by Jacobite recruiting parties looking for warm bodies to join the cause. Requisition officers wrote up strict demands for civic officials to provide supplies for the benefit of the Bonnie Prince’s war effort, and Gàidhlig-speaking strangers in Highland clothing were billeted in private homes without regard for the owners’ approval. Few political conversations occurred openly, as one never knew who was listening in. Clandestine meetings and furtive confabulation concerning treasonous topics were not uncommon occurrences in Coupar Angus, nor in any locality where Jacobite designs were taking shape.

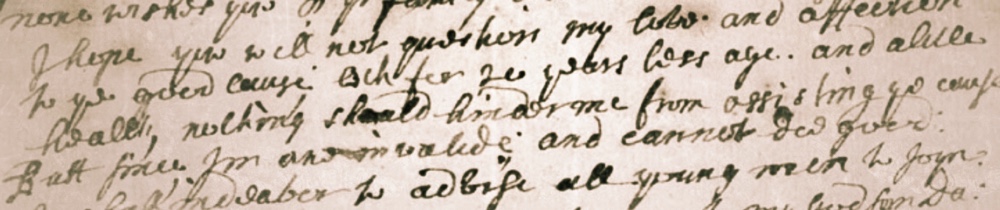

According to the accounts of several common citizens throughout the rural Scottish Lowlands, this harvest season brought with it a palpable frisson that many regarded with equal parts excitement, trepidation, and ambivalence. Though the last Jacobite rising quickly gained momentum in its opening weeks, many participants knew even at that bullish time that success for Forty-five was by no means a sure thing. Matters were especially complicated for those who wanted to remain neutral or otherwise avoid being involved in such a dangerous gambit. And despite the profound vein of Jacobite support that ran through a broad range of disparate Northern Britons, the overwhelming majority of Scotland’s population was firmly set against the idea of a return to Divine Right monarchy under the Stuart kings.1