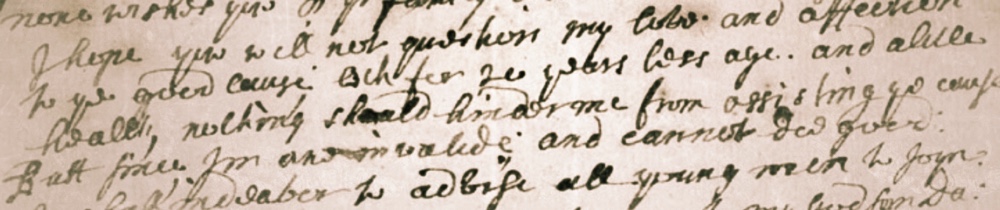

I hope yew will not question my love and affection to ye good cause. Och for 20 years less age, and a little health, nothing should hinder me from assisting ye cause. Butt since I’m ane invalide and cannot doe good, I shall indeaver to advise all young men to Joyn.

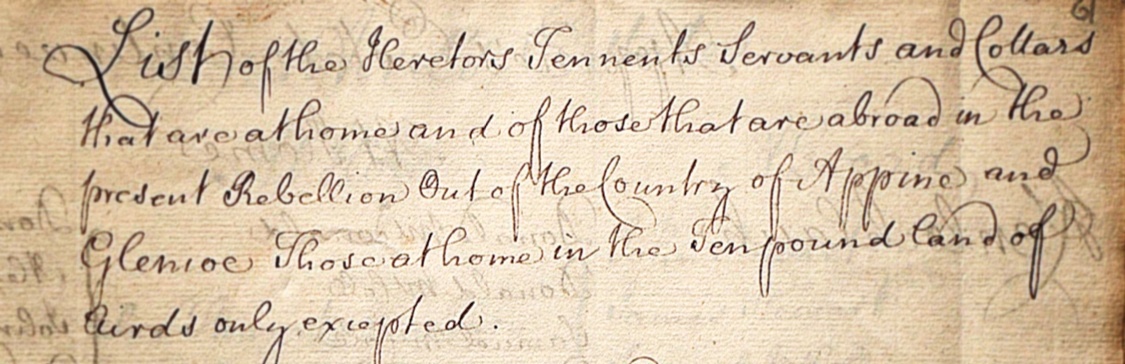

There were a number of different reasons why someone might join the Jacobite army in the late summer of 1745, just as things were starting to heat up after the arrival of Bonnie Prince Charlie in the Western Isles of Scotland. Specific motivations to pick up arms or to help others to do so were as disparate and multi-layered as the individuals involved in the conflict, as were their levels of sustained commitment as the campaign progressed.

Some fought for the ancient claim of the Stuart monarchs, and some stood in opposition to the parliamentary union that bound together England and Scotland into a single kingdom. Many resented being forced to accept the authority of the presbyteries over the traditional Divine Right of kings, especially when it came bundled with oaths of fealty to a sovereign from Lower Saxony. Others reckoned that they would be better off without the influence of a comparatively liberal representative government, an establishment which to them symbolized the decay of traditional values – especially in certain long-established and autonomous regions of ‘North Britain’.1