To reinforce our recent discussion of critical thinking about the historical data used within a project like JDB1745, this week’s post illustrates an example of that application in action. While looking through some of the published trial records related to government prosecution of the Manchester regiment, team member Bill Runacre found a data conflict that took a bit of detective work to iron out. In the 1816 trial transcript of Captain James Bradshaw, published in Vol. XVIII of Howell’s (or Corbett’s) State Trials, amongst the witnesses who took the stand against the Manchester officer was one Henry Gibson, allegedly a soldier in Elcho’s Jacobite cavalry troop. Some character notes about Gibson are described within the transcript:

Henry Gibson was also produced and sworn, who said, That he himself was unfortunately seduced into the rebel army, and entered into lord Elcho’s troop of horse-guards; that the prisoner, Mr Bradshaw, marched with them as a private man in the said corps; that the troop was drawn up at the battle of Culloden, and that he there saw the prisoner on horseback in the said troop, with pistols, and a broad sword by his side, and a white cockade, and that he continued with the said troop till he was taken prisoner by his royal highness the duke of Cumberland’s army.1

Much of Gibson’s testimony against Bradshaw sounds quite similar to that of dozens of other witnesses brought in to inculpate suspected Jacobite prisoners in the years following the failure of the final rising. Pertinent details which the government found most helpful often included firsthand descriptions of the defendant’s presence within the Jacobite army and specific duties in that station, persons of repute with whom they were seen conversing, and the identification of clothing and arms that were worn during their tenure in Jacobite service. The collective depositions by Gibson and those of at least eight other witnesses were enough to condemn James Bradshaw, and he was thus found guilty and subsequently executed in London on 28 November 1746. As it turns out, however, Henry Gibson did not actually exist.

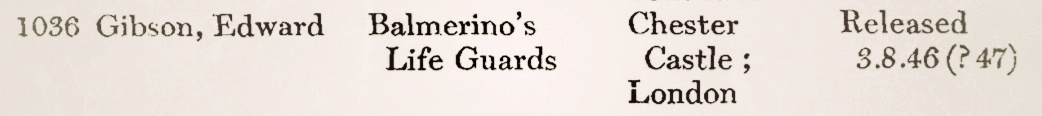

Searching through our database, team members could not find anyone with that name listed in any primary historical source from the period, let alone that of a significant contributor to the Jacobite trials and one whose testimony helped to seal the fates of numerous men. Working from the fact that this witness was himself involved in the Jacobite army, a quick comparison of eight unique Gibsons (nineteen across all sources) within JDB1745 brought up a likely candidate to fill the persona of Bradshaw’s witness. According to Seton and Arnot’s The Prisoners of the ’45 (hereafter P45), an Edward Gibson had turned King’s evidence and was sent to London to partake in the prosecutions of his fellow Jacobite soldiers.2 No other prisoner with that surname appears to have been involved in giving testimony.3

Consulting this secondary source, we were able to learn some other simple details about Edward Gibson: that he was a member of Lord Balmerino’s lifeguards (as opposed to Elcho’s, as shown in the trial transcript), and that he was held in Chester Castle and in London, where he was housed, along with other witnesses, with a government official named Carrington (Nathan, a crown messenger) during the trials. Also according to Seton and Arnot, Gibson was eventually released in August of 1747. More than this we cannot discern from their roster of Jacobite prisoners, but we were able to delve a bit deeper based upon three other documents which are cited as sources for their entry in P45. While their citation for the Scots Magazine does not tell us anything significant about Gibson, a reference to James Allardyce’s own trial transcriptions (1895) is more helpful.4 In this limited publication of court proceedings, Edward Gibson provides evidence against no fewer than five other prisoners, and we learn that he was indeed a private man in Balmerino’s troop who took part in the march to Derby and was present in the army all the way through to Culloden.5

Gibson’s true identity is beginning to take shape now, but thus far we have only been using a printed compilation taken from reprints of transcriptions which were originally made from unknown manuscripts(!). Thankfully, P45 offers a final citation from a traceable primary source within the State Papers, but due to the layers of cataloguing systems used by the National Archives through the years, the citation is no longer accurate.6 A quick search of TNA’s Discovery catalogue does bring up a few documents in the State Papers which are relevant to the man we are after, as well as a handful in the Treasury Solicitor Papers. None of these manuscripts are cited in P45, even though the compilers used both collections extensively for their three-volume work in 1928 – which remains a popular Jacobite-related biographical source and is frequently consulted by modern historians.7

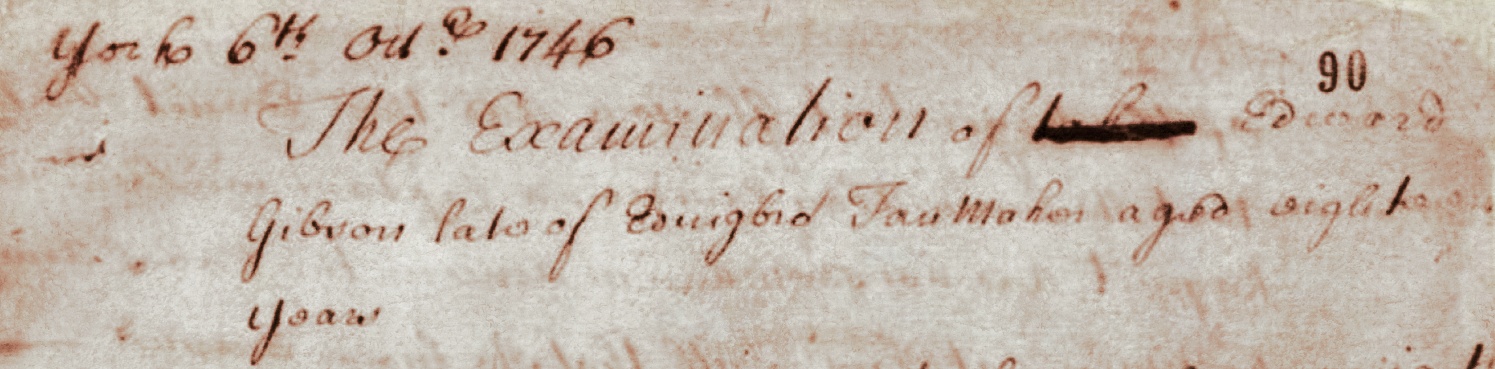

Turning toward those these documents, we can add considerable detail to the record of Edward Gibson and his part in the prosecution of his fellow Jacobite soldiers.8 In early October 1746, Crown Solicitor Phillip Carteret Webb first mentions in a letter to the Duke of Newcastle that he discovered Gibson at the trial of George Hamilton of Redhouse, and Webb believed that ‘he will turn out a very Material Witness against Several of the most Considerable of the Rebels that Remaine to be Tryed in London’. Webb immediately ordered Nathan Carrington to take Gibson into custody and obtain a full statement of everything he knew about his rebel associates – which was a significant amount. On 6 October, Gibson revealed the following in a detailed examination, which was promptly sent along to the office of Newcastle:

• That he was a fan-maker in Edinburgh and only eighteen years old.

• He had joined Elcho’s troop a month after the Battle of Prestonpans but his command had subsequently been taken over by Balmerino on the march to Derby from Edinburgh.

• Gibson was present at Falkirk but his unit was not engaged in the battle, and he deserted the Jacobite army at Elgin about three weeks before the Battle of Culloden.

• From Elgin, he made his way southward to England, where he spent time in Hull and York for the five months before his capture.

• He provides the names of twenty particularly active Jacobite associates with whom he had had direct experience. In addition to their names, where possible Gibson also notes their rank and regiment, as well as what clothes they were wearing and which weapons they carried. Furthermore, he claimed to know ‘several other of the Rebel Officers’, but these are not included in his deposition.

Of the twenty-three men whom Edward Gibson names across these sources, it appears that he actually took the witness stand against only five of them (in addition to Hamilton of Redhouse). With the admission of his testimony into court, two of these men were found guilty and transported while only Bradshaw was executed. It would be a simple matter to cross-reference the above list against proofs of their capture and prison records to see which were prosecuted and if there was cause for Gibson to speak against them. At this time, however, the whereabouts of further trial transcriptions involving Gibson are unknown.

By the summer of 1747, most of the Jacobite trials had been concluded.9 Government witnesses would no longer be needed, and those who were promised leniency in exchange for information would seek full pardons for their ‘loyal’ service. We know that on 3 August of that year, Gibson and nine other former Jacobite soldiers – likely fellow witnesses – were discharged from Chester Castle, presumably into a life of freedom.10 Yet the date of Gibson’s release was a full eight months after Bradshaw’s execution, the last judicial event in which we know he was involved – a lengthy imprisonment for a state witness. Beyond all of this additional data, there is possibly still more information about Edward Gibson in the Patent and Chancery Rolls at Kew, as well as in the records from the Court of King’s Bench.

As we are so fond of emphasizing both here on Little Rebellions and within the greater JDB1745 project, even a minor mistranscription or sloppy reference error from generations past has a tendency to carry itself forward into the successive historiography and corrupt subsequent biographical information. This is a particularly onerous problem when dealing with large amounts of data like those used in prosopographical studies. In the case of our man Gibson, what started out as a simple naming conflict in an otherwise-trusted source quickly became a new thread of useful information that conferred a brace of advantages: first, it allowed us to definitively clear up that tiny morsel of the historical record, and two, it lured us down a path which added a significant amount of color to the biography of a minor but significant player in the final Jacobite rising.

Darren S. Layne received his PhD from the University of St Andrews and is creator and curator of the Jacobite Database of 1745, a wide-ranging prosopographical study of people concerned in the last rising. His historical interests are focused on the mutable nature of popular Jacobitism and how the movement was expressed through its plebeian adherents. He is a passionate advocate of the digital humanities, data and metadata cogency, and Open Access.

Per Oates, John (The Manchester Regiment of 1745 in Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Vol. 88, No. 354 (Summer 2010);) Bradshaw transferred into Lord Elcho’s regiment at Carlisle, after an argument with its Colonel, Francis Towneley. Which ties into Gibson’s evidence.

Good stuff, Tim. It’s always nice to find those extra bits of corroborating information. Thanks for reading along and commenting!

[…] its context. Following and challenging that data lineage is something about which I have repeatedly written, and this pursuit represents a significant role in the methodology of my everyday work, as I […]